On-farm hatching is now fairly common in some countries, it requires incubated eggs to be transported from the hatchery to the farm at 18–18.5 days of incubation and they must arrive on the farm before external pipping starts.

The embryos need to be kept vital during transport to ensure a good hatch on the farm. The incubated eggs must have sufficient oxygen; shocks and jolts must be minimised; and the temperature must be controlled.

This raises the question whether we can simply apply the same set point temperature in the truck as in the hatcher, which is approx. 36 °C (97 °F). We could indeed do this if air speed over the incubated eggs were similar, but we can assume this will not be the case. In the temperature-controlled truck, depending on its design, air speed will be lower, as will be the uniformity of air speed.

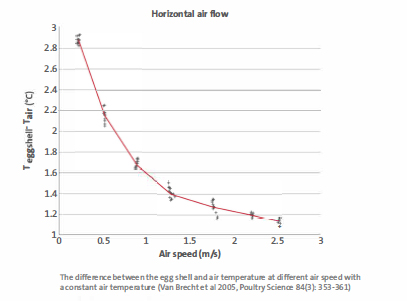

18-day old embryos produce approx. 170 – 180 Watt of heat per 1000 eggs. To avoid embryo temperature becoming too high, this heat has to be removed by circulating cooler air. The graph below shows that the lower the air speed over an individual egg (e.g. 0.5 m/sec as opposed to 2.0 m/sec), the greater the difference between the temperature of the egg shell and that of the circulating air. In other words, at a constant air temperature, incubated eggs exposed to a lower air speed will be warmer than eggs exposed to a higher air speed. Moreover, air speed will not be the same over all eggs in the load. The graph also shows that the uniformity of egg shell temperature will be more negatively affected by variation of air speed in the lower air speed range. To make matters worse, it is most likely that the air flowing over the eggs will not be at a constant temperature, especially when air speed is low, and as a result hot spots are likely to develop.

Generally, the following statements apply during transport of 18-day incubated eggs:

- Overheating (some) eggs does greater harm than cooling (some) eggs to below optimum temperature; overheating can kill the embryo or affect the quality of the day-old chicks, whereas temporary undercooling only slows down the hatch, which might actually be an advantage over longer transport distances.

- The lower the air speed over the eggs, the lower the temperature in the truck should be.

- The greater the variation in air speed over the eggs, the lower the temperature in the truck should be, in order to avoid a few eggs in an area with low air speed becoming overheated.

Note, however, that air speed over the incubated eggs depends not only on truck design, but also on how the eggs are transported. Eggs on setter trays in spacious trolleys can be transported at a higher temperature than eggs that are tightly packed together.

Advice

- Apply a lower air temperature for transporting 18-day incubated eggs than you would do in the hatcher; temperatures typically used in practice are between 25 and 32 °C (77 – 90 °F).

- Be aware that the air close to the sensor in the body of the truck is likely to be cooler than the air between the eggs.

- Monitor egg shell temperature during transport and adjust air temperature accordingly.

- Bear in mind that aiming for an egg shell temperature of 100 °F carries the risk of some eggs becoming too warm due to lower uniformity; a safe range between too cold and too warm is 90 – 96 °F.