Coccidiosis is caused by intra-cellular enteric protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria. Eimeria is a gastrointestinal parasite with a complex life cycle involving an endogenous phase occurring in the intestinal tract of the turkeys and an exogenous phase occurring outside the host. Turkeys infected with Eimeria shed oocysts that are unsporulated and non-infections. Sporulation occurs in the environment under optimum temperature, moisture, and oxygen. Sporulated oocysts are infectious and when ingested by naïve turkeys they adversely affect the intestinal health resulting in subclinical or clinical coccidiosis.

➤ Vijay Durairaj and Ryan Vander Veen

Huvepharma, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Corresponding Author: Vijay.Durairaj@huvepharma.us

Coccidiosis is a highly important enteric disease in turkeys causing significant economic impact. During the endogenous phase, Eimeria replicates in the intestinal epithelium and compromises the integrity of the intestine. It causes malabsorption, dehydration, decreased feed intake and compromises growth and production. Economic losses are from decreased production, poor feed conversion, retarded growth rate and increased mortalities. Indirect economic losses include the cost of coccidiosis treatment. Affected birds may exhibit non-specific clinical signs of coccidiosis such as anorexia, unthrifty appearance, listlessness, huddling, ruffled feathers, droopy wings, and enteritis. Wet litter can be easily noticed in flocks with clinical coccidiosis. Severe infection results in mortalities and production losses attributable to clinical coccidiosis. The severity and the outcome of coccidiosis depends on various factors such as the virulence of the Eimeria isolate, age of the birds, flock density, oocyst load in the barn, health and immune status of the birds and concurrent enteric infections in the barn.

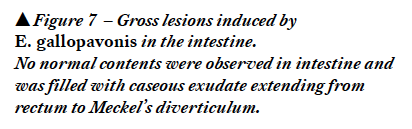

Each Eimeria species affects a specific region in the intestine. In mild and subclinical infections, the gross lesions are not very well pronounced and are indistinct. Additionally, the gross lesions of turkey Eimeria species should be differentiated from nonspecific lesions such as hyperemia and congestion. In field conditions, not all turkeys are infected or exposed to Eimeria species at the same time. Generally, the lesions induced by Eimeria species during the endogenous replication phase can be determined by dissecting and evaluating the intestine. In some instances, the severity of the infection might result in mortalities before the birds are evaluated for intestinal lesions. In the case of mild infections, the intestinal lesions may not be outstanding. In some instances where the intestines are evaluated after the prepatent period, there are more chances for the intestinal lesions to resolve. The prepatent period varies between the different Eimeria species. Thus, the time frame for performing the necropsy and evaluating the intestine is crucial, as the intestinal lesions are usually a result of the damage incurred by the endogenous replication cycle. Eimeria species are ubiquitous in turkey raising facilities due to prolific replication in the intestine and the resistance of oocysts to harsh environmental conditions. Seven Eimeria species have been documented in turkeys which includes E. meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis, E. dispersa, E. innocua, E. meleagridis, and E. subrotunda. Among these Eimeria species, E. meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides and E. gallopavonis are highly pathogenic (1,4) and identified as predominant (2). This paper elaborates the pathological manifestation of the highly pathogenic and predominant Eimeria species of turkeys.

Eimeria species are ubiquitous in turkey raising facilities due to prolific replication in the intestine and the resistance of oocysts to harsh environmental conditions. Seven Eimeria species have been documented in turkeys which includes E. meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis, E. dispersa, E. innocua, E. meleagridis, and E. subrotunda. Among these Eimeria species, E. meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides and E. gallopavonis are highly pathogenic (1,4) and identified as predominant (2). This paper elaborates the pathological manifestation of the highly pathogenic and predominant Eimeria species of turkeys.

E. meleagrimitis

The clinical signs of E. meleagrimitis can be noticed four days after infection. E. meleagrimitis causes non-specific clinical signs such as listlessness, dullness, depression, huddling, unthrifty appearance and ruffled feathers. The feces may be watery with mucus, orange or brown colored with blood flecks. The intestinal lesions are evident at 5 days after challenge (3). In severe cases, mortalities may occur between 6-8 days after infection.

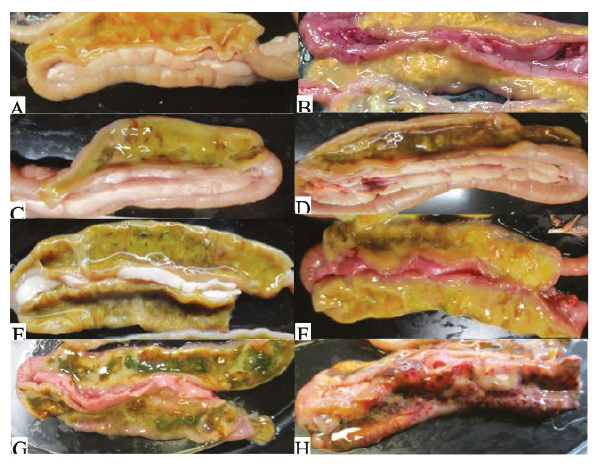

E. meleagrimitis affects the upper small intestine, targeting the duodenum and proximal jejunum. In severe infections, the lesions may extend to the lower intestine. E. meleagrimitis results in an accumulation of mucus in the affected regions of the intestine. E. meleagrimitis oocysts penetrate deep and cause severe damage to the intestinal epithelium resulting in sloughing and enteritis.

Pathological manifestations in the duodenum may include watery, yellow and mucoid contents (Figure 2A), watery contents with yellow fibrin strands (Figure 2B), yellow mucoid contents with few blood clots (Figure 2C), brown watery contents with yellow mucoid contents (Figure 2D), yellow and green watery mucoid contents with fibrin and few blood clots (Figure 2E), yellow and orange mucoid contents along with diphtheritic membrane covering the intestinal mucosa (Figure 2F), orange, yellow and greenish (bile stained) mucoid contents (Figure 2G), and thickened duodenal wall with numerous petechiae and ulcerations, edematous, extensive hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 2H).

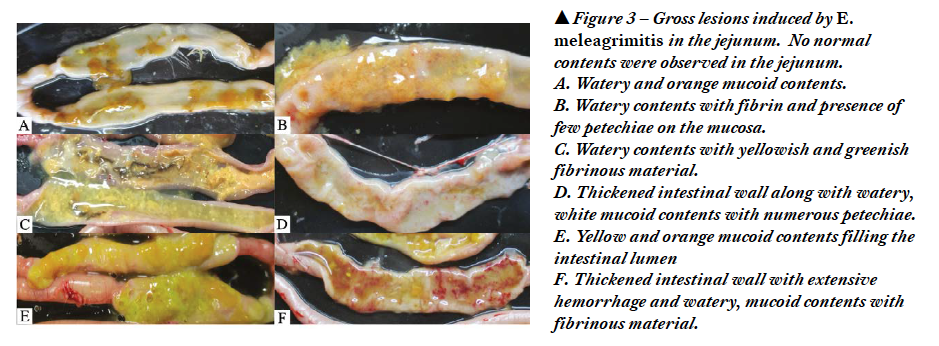

Pathological manifestations in the jejunum may include watery and orange mucoid contents (Figure 3A), watery contents with fibrin and presence of few petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 3B), watery contents with yellowish and greenish (bile stained) fibrinous material (Figure 3C), thickened intestinal wall along with watery, white mucoid contents with numerous petechiae (Figure 3D), yellow and orange mucoid contents filling the intestinal lumen (Figure 3E), and thickened intestinal wall with extensive hemorrhage and watery, mucoid contents with fibrinous material (Figure 3F).

Pathological manifestations in the jejunum may include watery and orange mucoid contents (Figure 3A), watery contents with fibrin and presence of few petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 3B), watery contents with yellowish and greenish (bile stained) fibrinous material (Figure 3C), thickened intestinal wall along with watery, white mucoid contents with numerous petechiae (Figure 3D), yellow and orange mucoid contents filling the intestinal lumen (Figure 3E), and thickened intestinal wall with extensive hemorrhage and watery, mucoid contents with fibrinous material (Figure 3F).

E. gallopavonis

E. gallopavonis

The clinical signs of E. gallopavonis may be noticed five days after infection. E. gallopavonis causes non-specific clinical signs such as listlessness, loss of appetite, unthrifty appearance, huddling and ruffled feathers. E. gallopavonis affects and induces lesions in the ileum, cecal neck and rectum. The severity of lesions varies between field isolates. The intestinal lesions are evident at 6 days after challenge (3). In severe cases, mortality may occur between 6-9 days after infection.

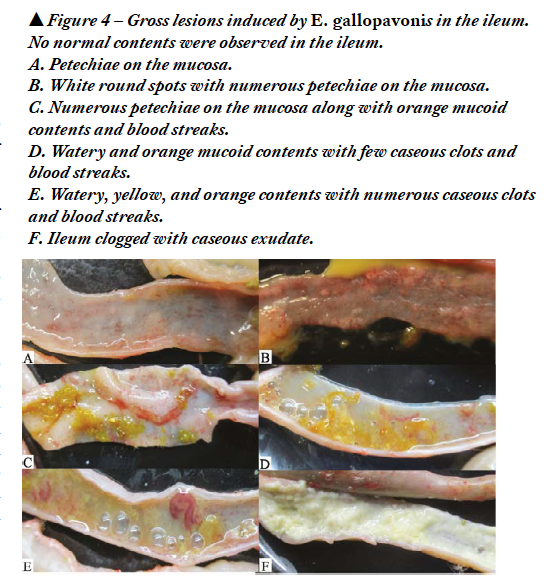

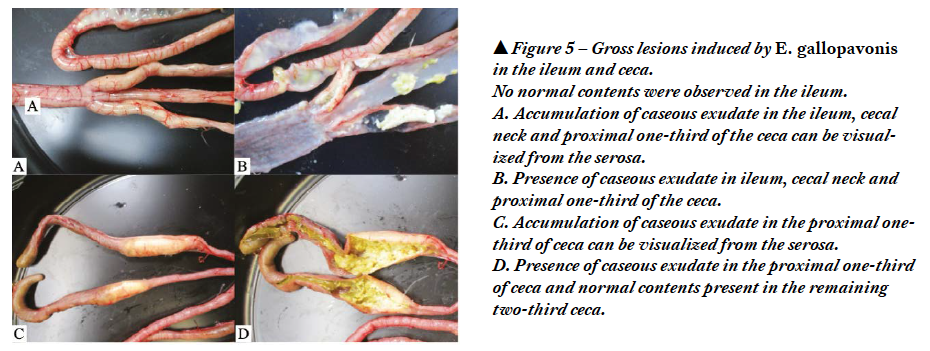

Pathological manifestations in the ileum include petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 4A), white round spots with numerous petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 4B), numerous petechiae on the mucosa with orange mucoid contents and blood streaks (Figure 4C), watery and orange mucoid contents with few caseous clots and blood streaks (Figure 4D), watery, yellow, and orange contents with numerous caseous clots and blood streaks (Figure 4E), and ileum clogged with caseous exudate (Figure 4F).The caseous clots in the ileum may extend to the anterior ceca. The ileum, cecal neck (Figure 5A) and proximal one-third of ceca stuffed with caseous exudate (Figure 5A, 5C) can be visible outside the serosa. Presence of caseous exudate in the ileum, cecal neck (Figure 5B) and proximal one-third of ceca (Figure 5B, 5D) can be seen on dissecting the intestine.

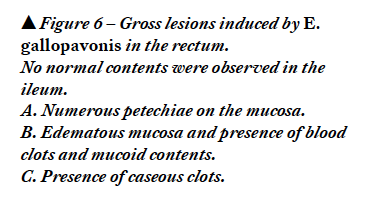

Pathological manifestations in the ileum include petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 4A), white round spots with numerous petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 4B), numerous petechiae on the mucosa with orange mucoid contents and blood streaks (Figure 4C), watery and orange mucoid contents with few caseous clots and blood streaks (Figure 4D), watery, yellow, and orange contents with numerous caseous clots and blood streaks (Figure 4E), and ileum clogged with caseous exudate (Figure 4F).The caseous clots in the ileum may extend to the anterior ceca. The ileum, cecal neck (Figure 5A) and proximal one-third of ceca stuffed with caseous exudate (Figure 5A, 5C) can be visible outside the serosa. Presence of caseous exudate in the ileum, cecal neck (Figure 5B) and proximal one-third of ceca (Figure 5B, 5D) can be seen on dissecting the intestine. The rectum may have numerous petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 6A), edematous mucosa and presence of blood clots and mucoid contents (Figure 6B) and caseous clots (Figure 6C).

The rectum may have numerous petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 6A), edematous mucosa and presence of blood clots and mucoid contents (Figure 6B) and caseous clots (Figure 6C).

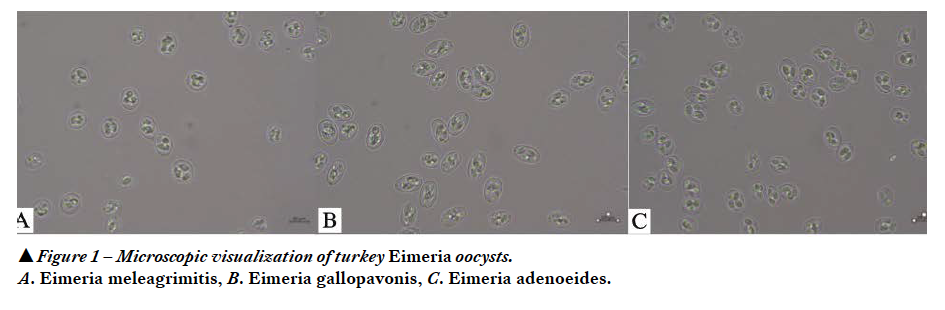

In severe cases, the caseous exudate may extend from Meckel’s diverticulum to the rectum (Figure 7).

In severe cases, the caseous exudate may extend from Meckel’s diverticulum to the rectum (Figure 7).

E. adenoeides

The clinical signs of E. adenoeides can be noticed 4 days after infection. Non-specific clinical signs such as dullness, depression, anorexia, ruffled feathers and listlessness may be noticed. The feces may be watery, orange mucoid and contain solid caseous casts and few blood specks. Unlike cecal coccidiosis in chickens, cecal coccidiosis in turkeys doesn’t cause severe blood loss. The intestinal lesions are evident at 5 days after challenge (3). In severe cases, mortalities may occur between 5-7 days after infection.

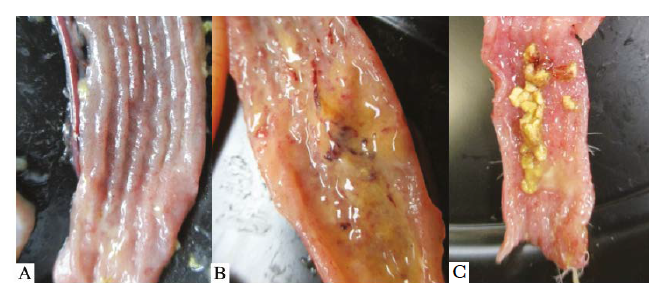

E. adenoeides is one of the highly pathogenic Eimeria species affecting the ceca of turkeys. On external examination of the ceca, the gross lesions may be outstanding in severe cases. Healthy ceca appear as pouches filled with dark green contents (Figure 8A). E. adenoeides infected ceca results in caseous materials (Figure 8B) and corrugated cecal core (Figure 8C) which could be visualized before dissecting the ceca. E. adenoeides causes sloughing of the mucosal epithelium and induces necrosis in the ceca.

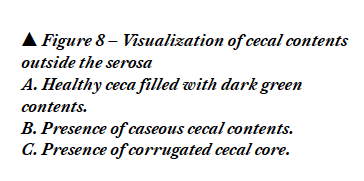

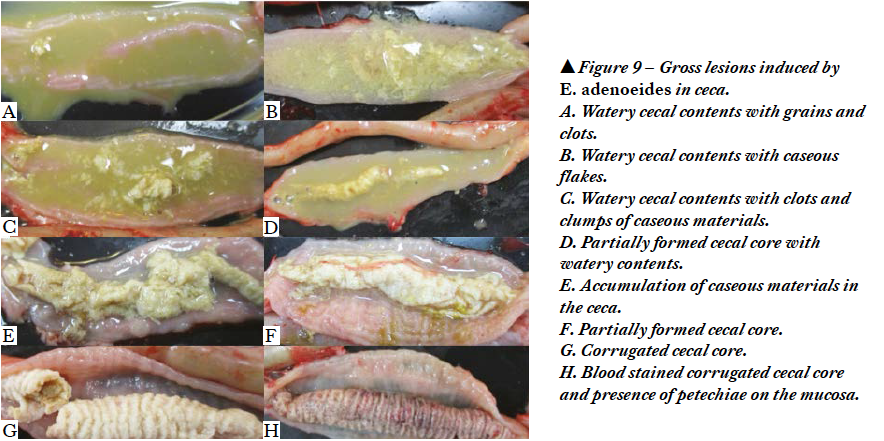

The pathological manifestation of E. adenoeides includes watery cecal contents with grains and clots (Figure 9A), watery cecal contents with caseous flakes (Figure 9B), watery cecal contents with clots and clumps of caseous materials (Figure 9C), partially formed cecal core with watery contents (Figure 9D), accumulation of caseous materials in the ceca (Figure 9E), partially formed cecal core (Figure 9F), corrugated cecal core (Figure 9G), and blood stained corrugated cecal core and presence of petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 9H). The cecal core is formed by sloughed cecal epithelium, cecal contents, dead cells, gamonts and oocysts of E. adenoeides.

The pathological manifestation of E. adenoeides includes watery cecal contents with grains and clots (Figure 9A), watery cecal contents with caseous flakes (Figure 9B), watery cecal contents with clots and clumps of caseous materials (Figure 9C), partially formed cecal core with watery contents (Figure 9D), accumulation of caseous materials in the ceca (Figure 9E), partially formed cecal core (Figure 9F), corrugated cecal core (Figure 9G), and blood stained corrugated cecal core and presence of petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 9H). The cecal core is formed by sloughed cecal epithelium, cecal contents, dead cells, gamonts and oocysts of E. adenoeides.

Turkey coccidiosis does not induce any specific clinical signs. The non-specific clinical signs of coccidiosis can easily be confused with the clinical signs of other enteric diseases in turkeys. Thus, gross lesions in the intestines and microscopic examination of oocysts are helpful in detecting the Eimeria species. Notably in field cases of turkey coccidiosis the gross lesions are not as outstanding as in chickens. In cases of concurrent infections with other enteric pathogens, diagnosis of coccidiosis based only on the gross lesions can be difficult in turkeys. In mixed and subclinical infections without any distinct gross lesions in the intestine, molecular tools such as PCR and sequencing can aid in confirming the Eimeria species.

Turkey coccidiosis does not induce any specific clinical signs. The non-specific clinical signs of coccidiosis can easily be confused with the clinical signs of other enteric diseases in turkeys. Thus, gross lesions in the intestines and microscopic examination of oocysts are helpful in detecting the Eimeria species. Notably in field cases of turkey coccidiosis the gross lesions are not as outstanding as in chickens. In cases of concurrent infections with other enteric pathogens, diagnosis of coccidiosis based only on the gross lesions can be difficult in turkeys. In mixed and subclinical infections without any distinct gross lesions in the intestine, molecular tools such as PCR and sequencing can aid in confirming the Eimeria species.

References

- Chapman HD. Coccidiosis in the turkey. Avian Pathol. 2008 Jun;37(3):205-23.

- Duff AF, Briggs WN, Bielke JC, McGovern KE, Trombetta M, Abdullah H, Bielke LR, Chasser KM. PCR identification and prevalence of Eimeria species in commercial turkey flocks of the Midwestern United States. Poult Sci. 2022 Sep;101(9):101995.

- Gadde UD, Rathinam T, Finklin MN, Chapman HD. Pathology caused by three species of Eimeria that infect the turkey with a description of a scoring system for intestinal lesions. Avian Pathol. 2020. Feb;49(1):80-86.

- Lund, E.E. & Farr, M.M. (1965). Coccidiosis of the turkey. In H.E. Biester & L.H. Schwarte (Eds.), Diseases of Poultry 5th edn (pp. 1088-1093). Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press.