Cecal cores are a classical pathological gross lesion seen in field necropsies. Even though a presumptive diagnosis is made based on the visualization of the cecal cores, confirmative tests are needed to establish the etiology of the disease.

Cecal cores, a pathological manifestation in the ceca, are an easy diagnostic tool in chickens, but they are often misdiagnosed and deceptively interpreted in field cases. Understanding the diseases that cause cecal core formation helps in proper diagnosis. An infectious pathogen which targets the ceca can colonize the cecal mucosa and degrade its integrity and architecture, resulting in necrosis and sloughing of tissues. The denuded and sloughed necrotic tissues of the ceca, along with the cecal ingesta, form the cecal cores.

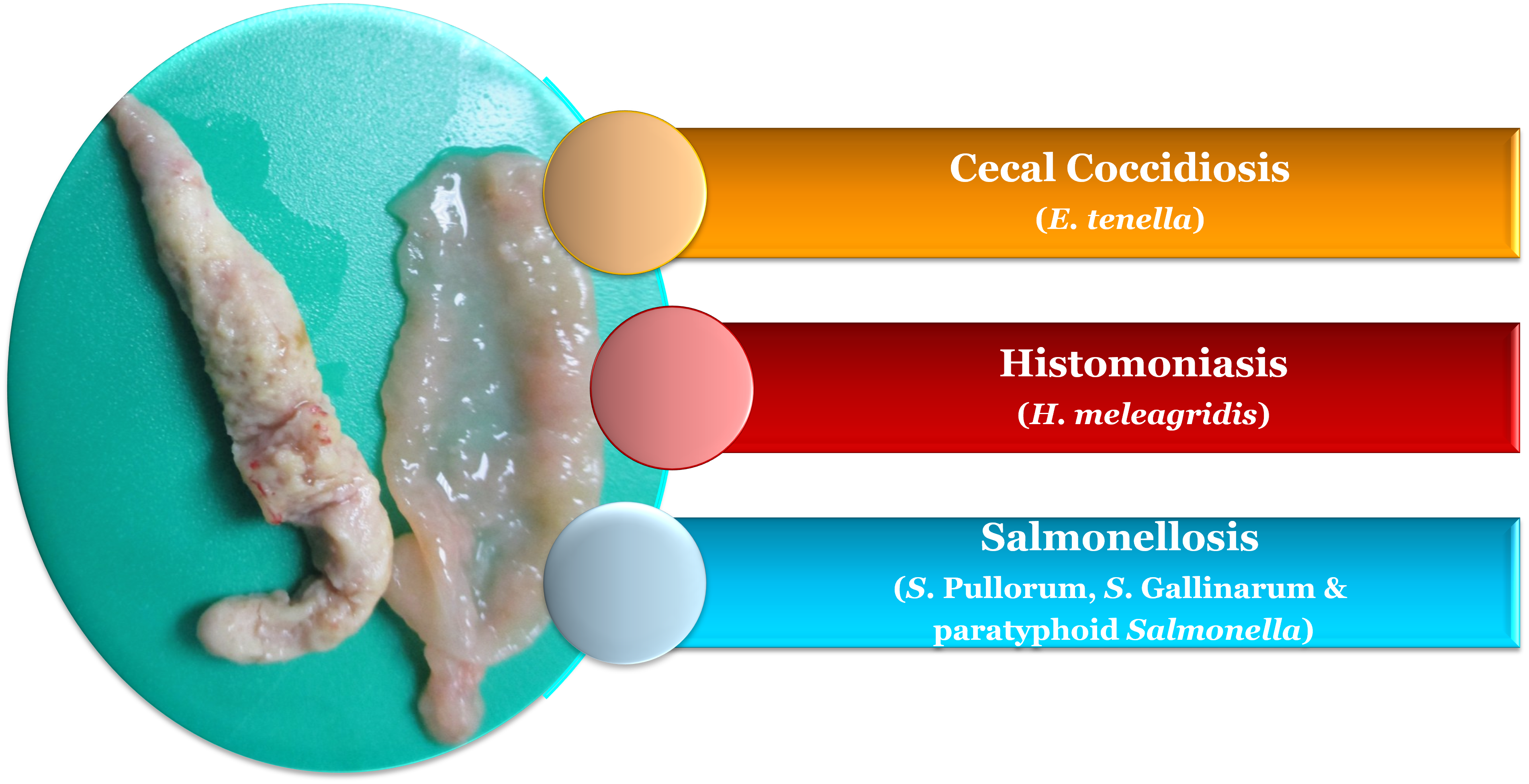

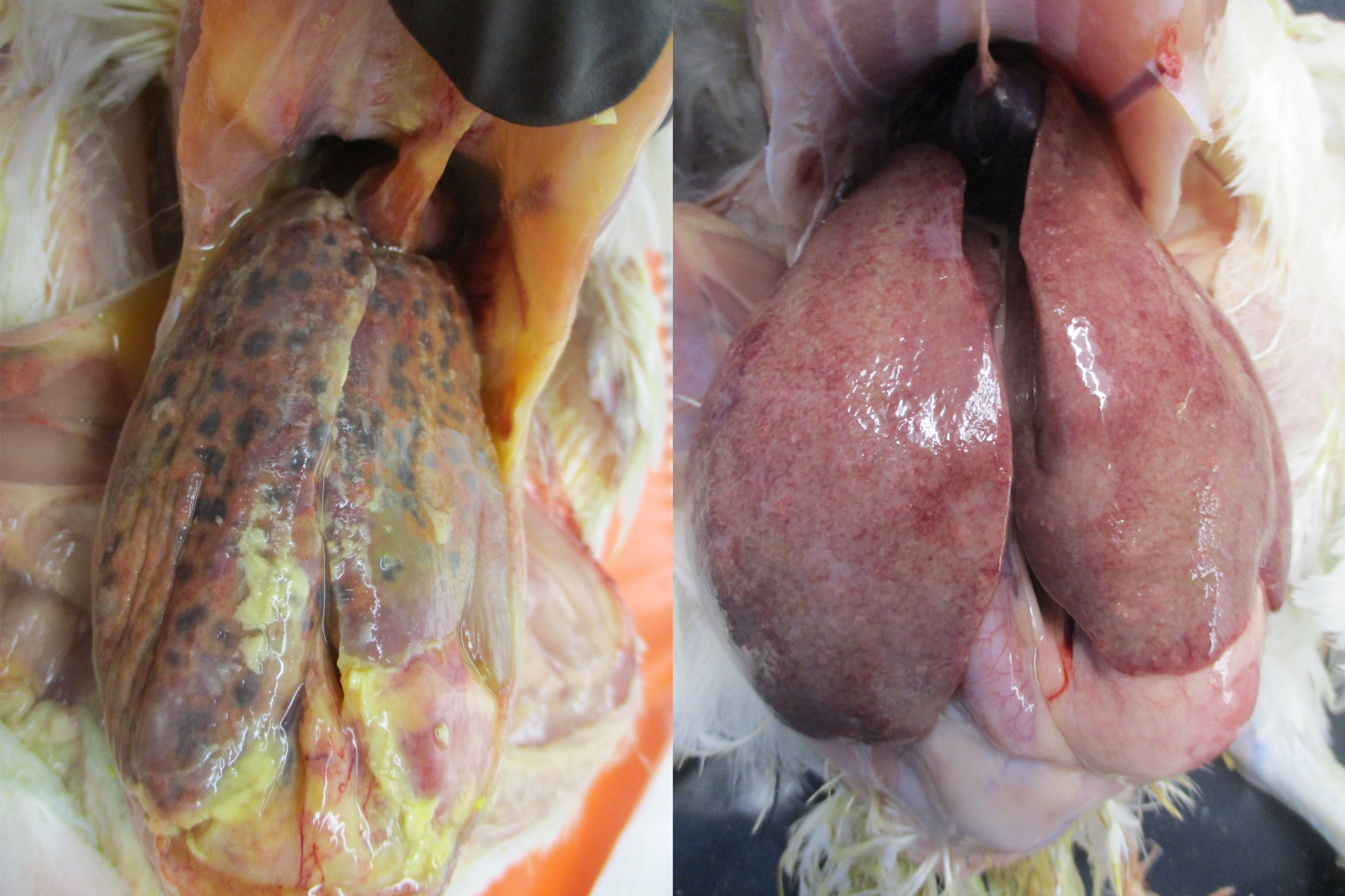

In chickens, enlarged and distended ceca with cecal cores could be found in diseases such as coccidiosis, histomoniasis and salmonellosis (Figure 1).

Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis in chickens is caused by Eimeria species. Despite prophylactic and therapeutic measures to combat coccidiosis, the eradication is difficult, as Eimeria species are ubiquitous in commercial poultry production facilities. There are several species of Eimeria targeting specific intestinal regions. E. tenella is one of the most pathogenic and common Eimeria species in chickens. It causes hemorrhage, inflammation, edema and thickening of the ceca and induces cecal cores formation (1). E. tenella is easily recognized because of its characteristic and spectacular lesions in the ceca. E. tenella is one of the pathogens that induces lesions in the ceca but is not the only one. Apart from Eimeria spp, H. meleagridis and Salmonella spp. can also induce lesions in the ceca.

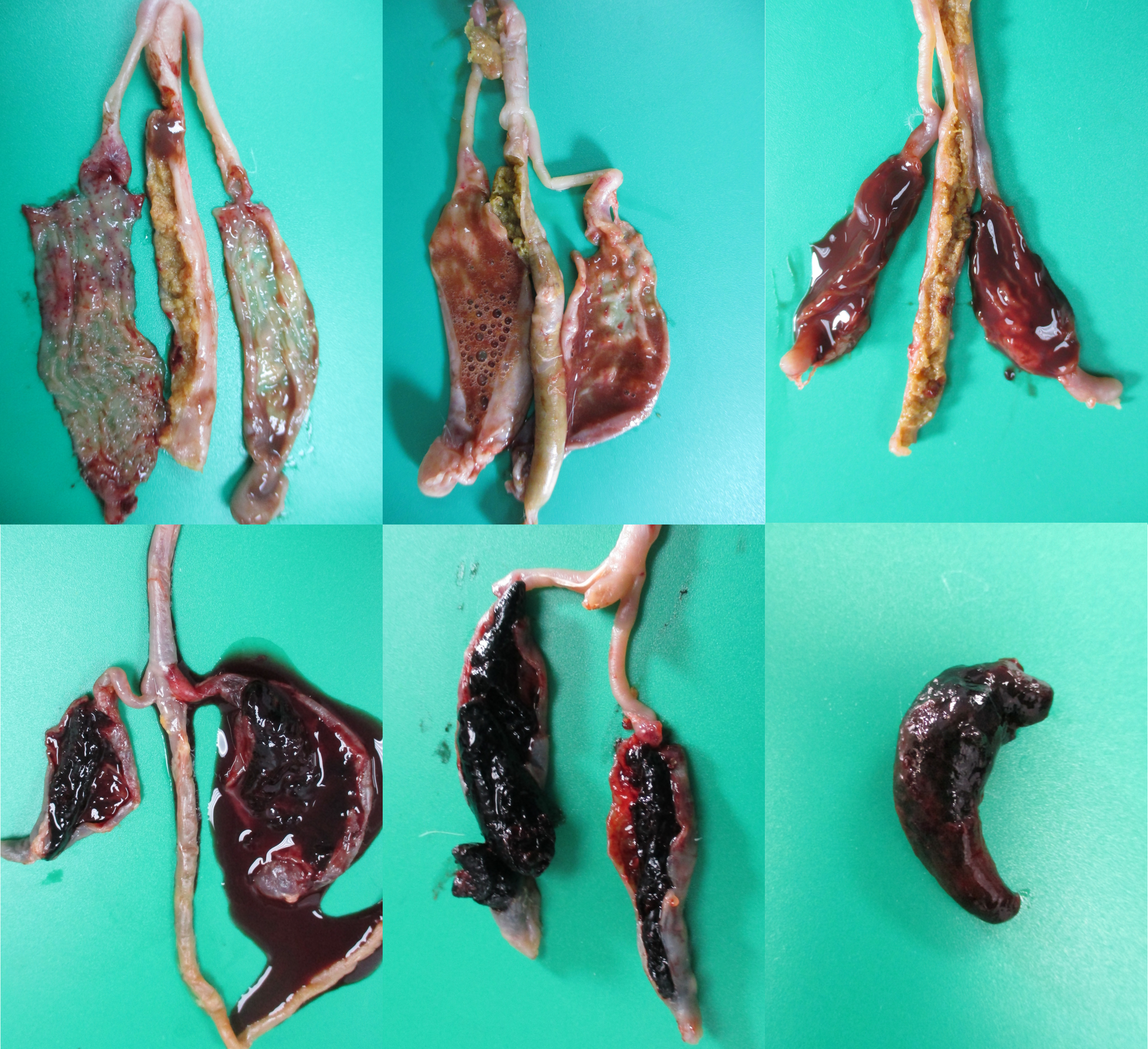

E. tenella penetrates deeply into the cecal mucosa and causes extensive destruction of the ceca and damages blood capillaries, resulting in hemorrhage and bloody diarrhea (Figure 2). This compromises the integrity of the ceca, affecting their routine function. tenella is target specific and commonly induces lesions in the ceca only. In very rare circumstances, E. tenella may invade adjacent intestinal sections (1). Unlike histomoniasis, E. tenella does not cause lesions in the liver. In severe cases, ceca engorged with bloody contents can be easily visualized on the serosa before dissecting them (Figure 3). E. tenella causes petechiae on the cecal mucosa with inflammation and congestion of the ceca (Figure 4A), abnormal and watery brownish/reddish cecal contents (Figure 4B), inflamed and thickened cecal wall with bloody contents in the lumen (Figure 4C), mixture of raw and clotted blood (Figure 4D), jelly-like clotted blood (Figure 4E), and solid cecal cores with clotted blood (Figure 4F).

A. Presence of numerous coalescing petechiae on the mucosa, inflammation and congestion of the ceca.

B. Abnormal and watery brownish/reddish cecal contents.

C. No normal contents in the ceca. Inflamed and thickened cecal wall and lumen filled with blood.

D. One of the cecal pouches have clotted blood and the other cecal pouch has a mixture of raw and clotted blood. Cecal pouches have thickened cecal wall.

E. Cecal lumen is filled with jelly-like clotted blood.

F. Hard cecal core formed with clotted blood, denuded cecal mucosa and cecal contents.

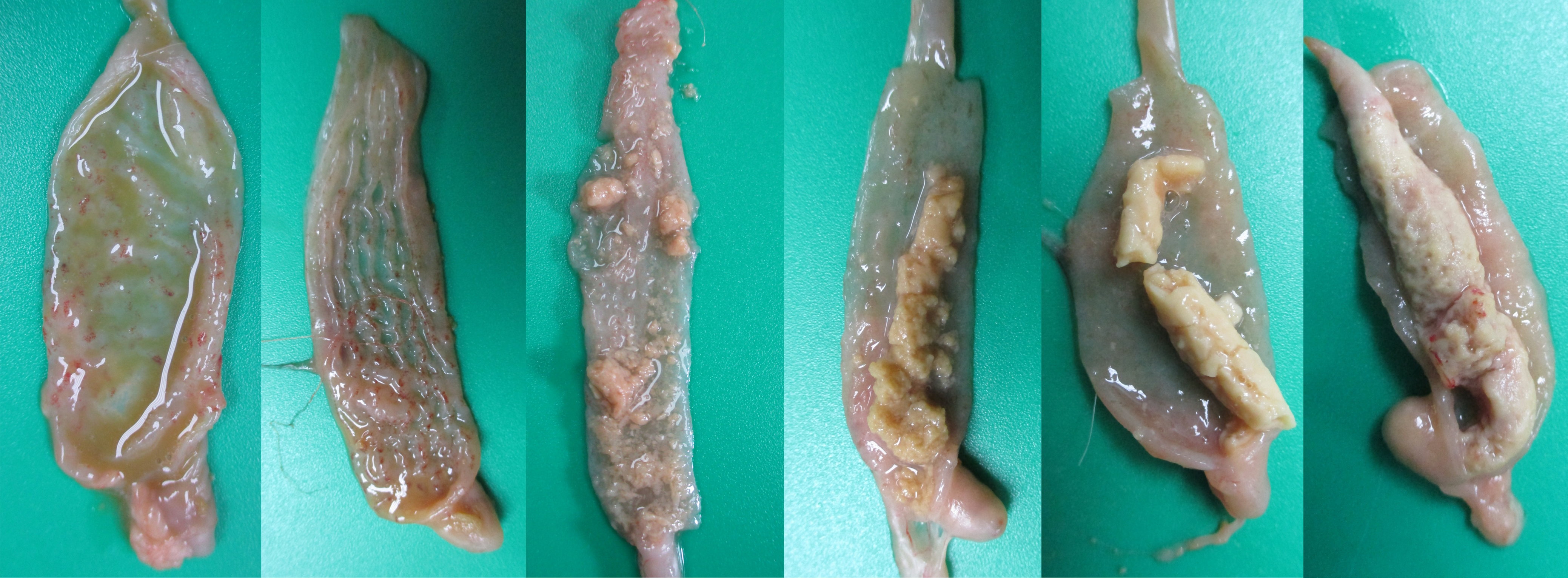

If the ceca have bloody/tarry contents or red jelly-like contents, the condition may be easily diagnosed as cecal coccidiosis. However, E. tenella is not the only pathogen that causes bleeding in the ceca, as H. meleagridis can cause similar lesions. Apart from bloody/tarry contents in the ceca, E. tenella may cause inflammation and induce formation of clots and chunks of caseous material and creamy-white caseous cores. The cecal lesions may range from petechiae on the mucosa (Figure 5A, 5B), to caseous clots (Figure 5C, 5D) and caseous cores (Figure 5E, 5F). These types of lesions may also be seen in histomoniasis and salmonellosis. H. meleagridis induces lesions in the ceca and in the liver, while E. tenella induces lesions only in the ceca. Salmonellosis may induce septicemic lesions in other visceral organs including the liver, while E. tenella does not induce any lesions in the liver.

A. Watery cecal contents. Thickened cecal wall with numerous petechiae.

B. Thickened cecal wall with numerous petechiae.

C. No normal contents in the ceca. Thickened cecal wall and presence of numerous caseous clots and clumps.

D. No normal contents in the ceca. Thickened cecal wall. Presence of coalescing caseous clots and clumps.

E. Thickened cecal wall with partially formed cecal core.

F. Thickened cecal wall with a solid cecal core.

Diagnosis of E. tenella is made based on gross pathology lesions in the ceca and identification of oocysts/schizonts/gametocytes from microscopic observation of the mucosal scraping from the ceca. Even if an outbreak of E. tenella is confirmed in the field, it is a best practice to rule out the possibility of concurrent infections.

Histomoniasis

Histomoniasis (blackhead disease, histomonosis, enterohepatitis) is caused by H. meleagridis. Heterakis gallinarum, the common cecal worm of gallinaceous birds, acts as an intermediate host for H. meleagridis. Broiler breeder and broiler breeder pullet farms have a heavy load of Heterakis gallinarum (2,3). With the unavailability of commercial vaccines and lack of prophylactic/therapeutic measures, increased incidences of histomoniasis are documented (4), in broiler breeder pullets (5) and free-range layers (6). In broiler breeder pullets, it causes high morbidity and the mortality ranges between 10-20% (7). H. meleagridis affects the ceca, inducing typhlitis and cecal cores formation and ultimately reaches the liver through systemic circulation (8).

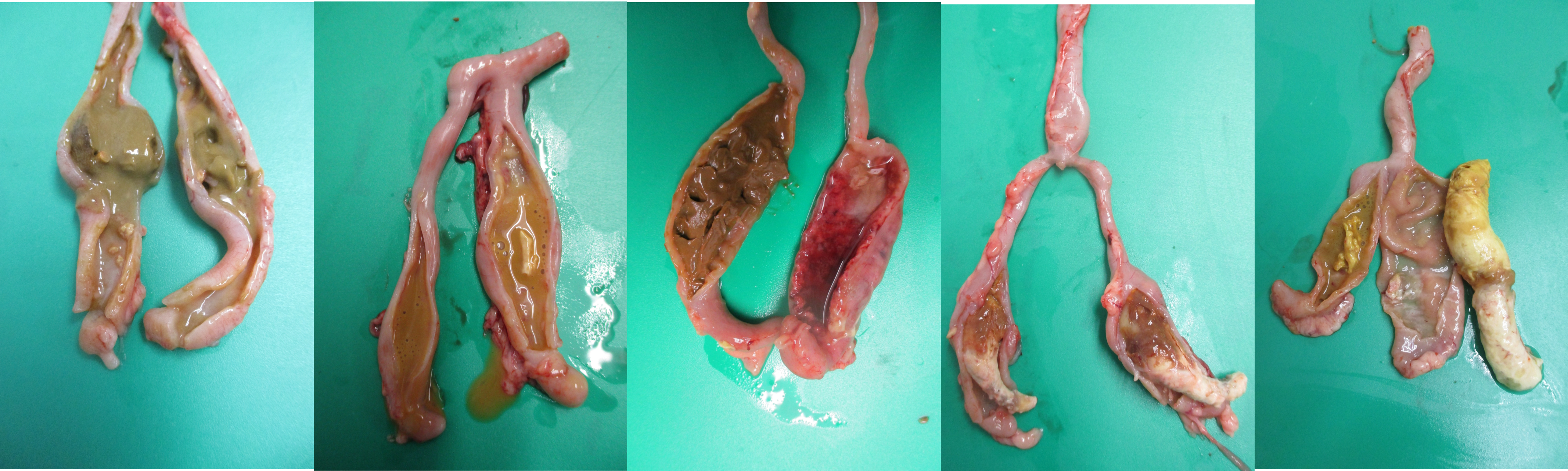

In the ceca, H. meleagridis affects the normal microbiota and induces severe lesions and formation of cecal cores. Sometimes, the presence of bloody contents in the ceca (Figure 6A) and presence of cecal cores (Figure 6B, 6C) can be easily visualized through the serosa before dissecting the ceca. The serosa may be hyperemic and inflamed (Figure 6A, 6B,6 C). The cecal wall may be thickened, hyperemic, inflamed, edematous and have abnormal contents (Figure 7A, 7B, 7C, 7D, and 7E). The ceca may have a mixture of normal cecal contents along with caseous clots (Figure 7A), watery contents and caseous clots (Figure 7B), bloody contents (Figure 7C), a mixture of normal contents and a cecal core (Figure 7D) and a solid cecal core (Figure 7E).

A. The serosa of both ceca are inflamed and congested with numerous petechiae. Both cecal pouches are engorged with bloody contents and are visible through serosa.

B. Left cecal pouch appears normal, while the distal third of the right cecal pouch is inflamed and engorged with caseous material.

C. Left cecal pouch appears normal, while the right cecal pouch is inflamed and engorged with caseous material.

A. Proximal one half of the ceca has a mixture of normal contents with caseous clots, while the other half of the ceca has watery contents with clots and clumps of caseous clots.

B. Left cecal pouch has watery contents, while right cecal pouch has watery contents with clots and clumps of caseous clots.

C. Left cecal pouch has normal contents, while right cecal pouch has thickened and edematous wall with numerous petechiae, watery contents and extensive hemorrhage.

D. One third of both cecal pouches have a mixture of normal contents and caseous core, while two third of the ceca have a solid caseous core.

E. Left cecal pouch has watery contents with caseous material, while right cecal pouch has a solid core.

The classic liver lesions induced by H. meleagridis aid in differentiating histomoniasis from coccidiosis. It may induce necrotic foci in the liver (Figure 8A) or pin-point white foci (Figure 8B). Sometimes, liver lesions in chickens may not be as severe and spectacular as in turkeys. H. meleagridis infection in chickens may cause severe cecal lesions without inducing any liver lesions. Severe liver degeneration and damage to the bile duct may result in yellow-colored droppings which result in yellow smear around the vent region (Figure 9). In some cases, H. meleagridis outbreaks may go unnoticed due to the lack of clinical signs or characteristic gross pathology lesions (9).

A. Septicemia, perihepatitis, hepatomegaly and presence of numerous coalescing black necrotic foci on the liver.

B. Hepatomegaly, discoloration and scattered pinpoint white necrotic foci on the liver.

Lesions in the ceca and liver can be used as presumptive diagnostic tools for histomoniasis and confirmed by histopathology, isolation of H. meleagridis or by molecular techniques. Evaluating the cecal scrapping under the microscope rules out the chance of concurrent infection with E. tenella. Bacterial culture testing of the lesions will aid in ruling out salmonellosis. Ruling out any concurrent infection is very important in histomoniasis diagnosis.

Salmonellosis

Host-adapted Salmonella, such as S. Pullorum, S. Gallinarum, as well as paratyphoid Salmonella, infections caused by non-host-adapted Salmonella, cause cecal lesions and may induce the formation of cecal cores (10). In acute cases, septicemia may lead to the development of gross lesions in the ceca, spleen, kidneys, lungs, heart and joints (10). Gross lesions may not be seen in peracute cases.

Young chickens are at high risk, and clinical signs are mostly observed in this age group. Clinical signs are nonspecific and may include watery diarrhea, white diarrhea with urate staining on the vent, dropped wings, stained feathers, anorexia, emaciation, depression, dehydration, weakness and chicks huddling under the heat source.

Salmonellosis can result in the formation of cecal cores in chickens (Figure 10A, 10B). In some cases, the cecal cores may be visualized through the serosa before dissecting it (Figure 10A). Due to the septicemic spread of Salmonella, gross lesions may be seen in other visceral organs including liver. The gross lesions in the ceca and liver do not confirm Salmonella infections, as these lesions alone are not specific and distinctive enough to differentiate them from other diseases. Thus, isolation and identification of Salmonella is needed to confirm the etiologic agent of the disease (Figure 10C). As always, rule out the chances of any concurrent infections.

A. One of the cecal pouches is engorged with cecal core. Serosa is transparent and the cecal core is visible without dissecting the ceca.

B. One of the cecal pouches has a solid cecal core and the other cecal pouch has normal fecal materials.

C. Black colonies of Salmonella on XLD agar plate.

Summary

Cecal cores are a classical pathological gross lesion seen in field necropsies. Even though a presumptive diagnosis is made based on the visualization of the cecal core, confirmative tests are needed to confirm the etiology of the disease. In addition, rule out any concurrent infections in the flock that cause similar lesions in the ceca.

References

- Cervantes, H. M., McDougald, L. R., & Jenkins, M. C. (2020). Coccidiosis. In D. Swayne, M. Boulianne, C. Logue, L. McDougald, V. Nair, D. Suarez, S. de Wit, T. Grimes, D. Johnson, M. Kromm, et al. (Eds.), Diseases of poultry (14th ed., pp. 1193–1216). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Waters, C. V. I., Hall, L. D., Davidson, W. R., Rollor, E. A. I., & Lee, K. A. (1994). Status of commercial and noncommercial chickens as potential sources of histomoniasis among wild turkeys. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 22, 43–49.

- Jones, R. E., Rives, D. V., Fletcher, O. J., & Martin, M. P. (2020). Histomoniasis outbreaks in commercial turkeys in the southeastern United States: Proximity of broiler breeder farms as a potential risk factor in disease development. Journal of Applied Poultry Research, 29, 496–501

- Liebhart, D., Ganas, P., Sulejmanovic, T., & Hess, M. (2017). Histomonosis in poultry: Previous and current strategies for prevention and therapy. Avian Pathology, 46(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2016.1229458

- Durairaj, V., Drozd, M., Barber, E., Doss, B., & Vander Veen, R. (2024, July/August). Case report: Histomoniasis in broiler breeder pullets. Zootecnica International, 36–42.

- Esquenet, C., De Herdt, P., De Bosschere, H., Ronsmans, S., Ducatelle, R., & Van Erum, J. (2003). An outbreak of histomoniasis in free-range layer hens. Avian Pathology, 32(3), 305–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307945031000097903

- McDougald, L. R. (1998). Intestinal protozoa important to poultry. Poultry Science, 77(8), 1156–1158. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/77.8.1156

- Clarkson, M. J. (1961). The blood supply of the liver of the turkey and the anatomy of the biliary tract with reference to infection with Histomonas meleagridis. Research in Veterinary Science, 2, 259–264.

- Chadwick, E., Malheiros, R., Oviedo, E., Cordova Noboa, H. A., Quintana Ospina, G. A., Alfaro Wisaquillo, M. C., Sigmon, C., & Beckstead, R. (2020). Early infection with Histomonas meleagridis has limited effects on broiler breeder hens’ growth and egg production and quality. Poultry Science, 99(9), 4242–4248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.05.020

- Gast, R. K., & Porter, R. E., Jr. (2020). Salmonella infections. In D. Swayne, M. Boulianne, C. Logue, L. McDougald, V. Nair, D. Suarez, S. de Wit, T. Grimes, D. Johnson, M. Kromm, et al. (Eds.), Diseases of poultry (14th ed., pp. 719–753). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell.