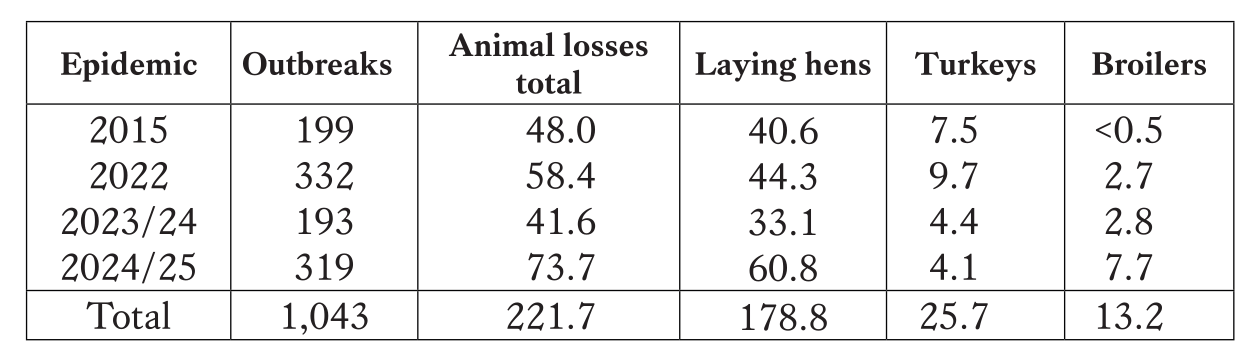

Between December 2014 and July 2025, the U.S. poultry industry has been hit by four devastating outbreaks of avian influenza (AI). In total, the highly pathogenic AI virus (HPAI) was diagnosed on 1,043 commercial poultry farms (1,932 total farms including backyard flocks). A total of 221.7 million poultry died due to virus infections or preventive culling. Of these, 178.8 million were laying hens, 25.7 million turkeys and 13.2 million broilers (Table 1). In this article, the temporal and spatial spread of the disease, its economic impact on egg production and the responses of the industry and the government are analysed.

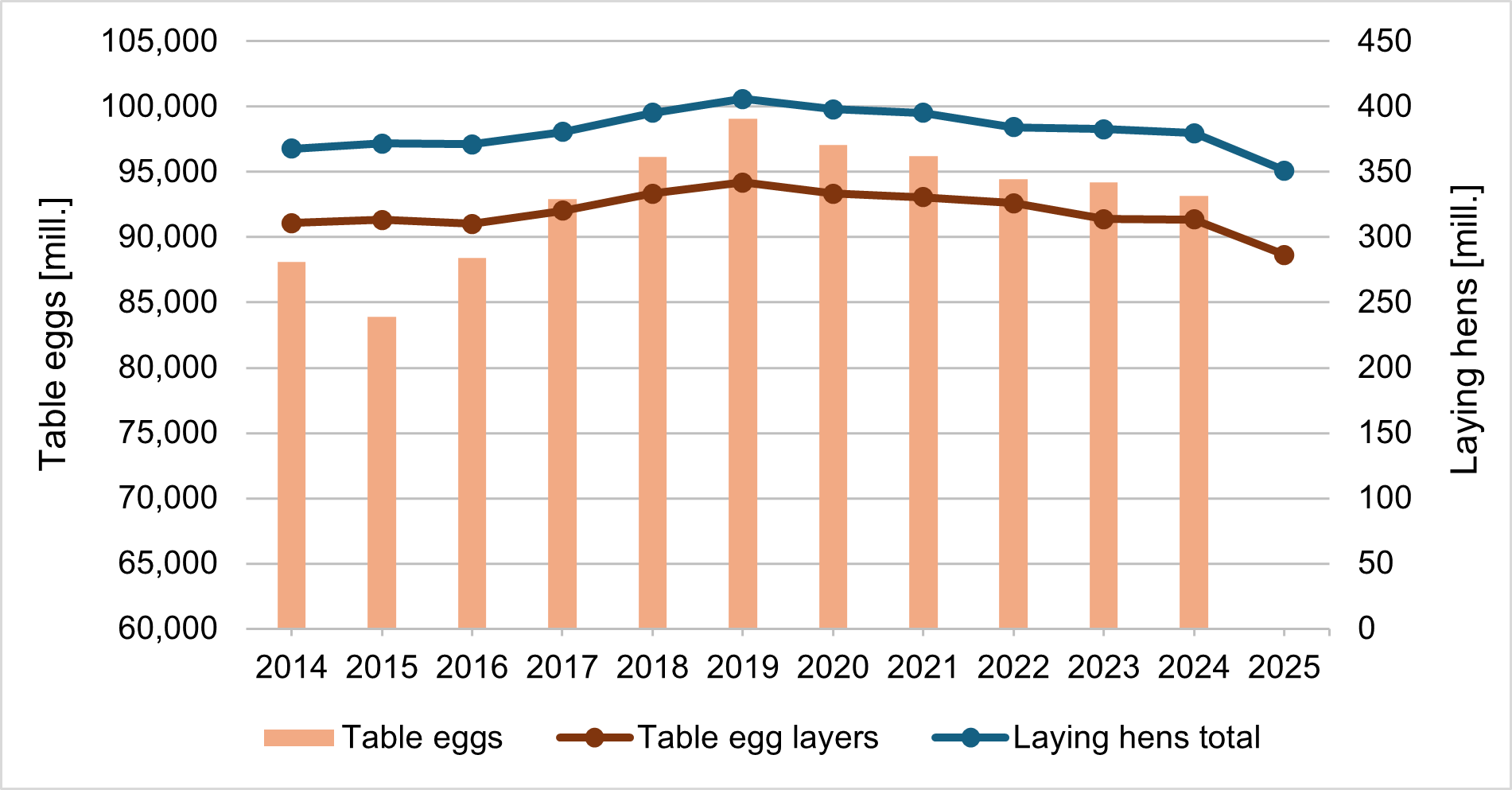

Sharp fluctuations in laying hen numbers

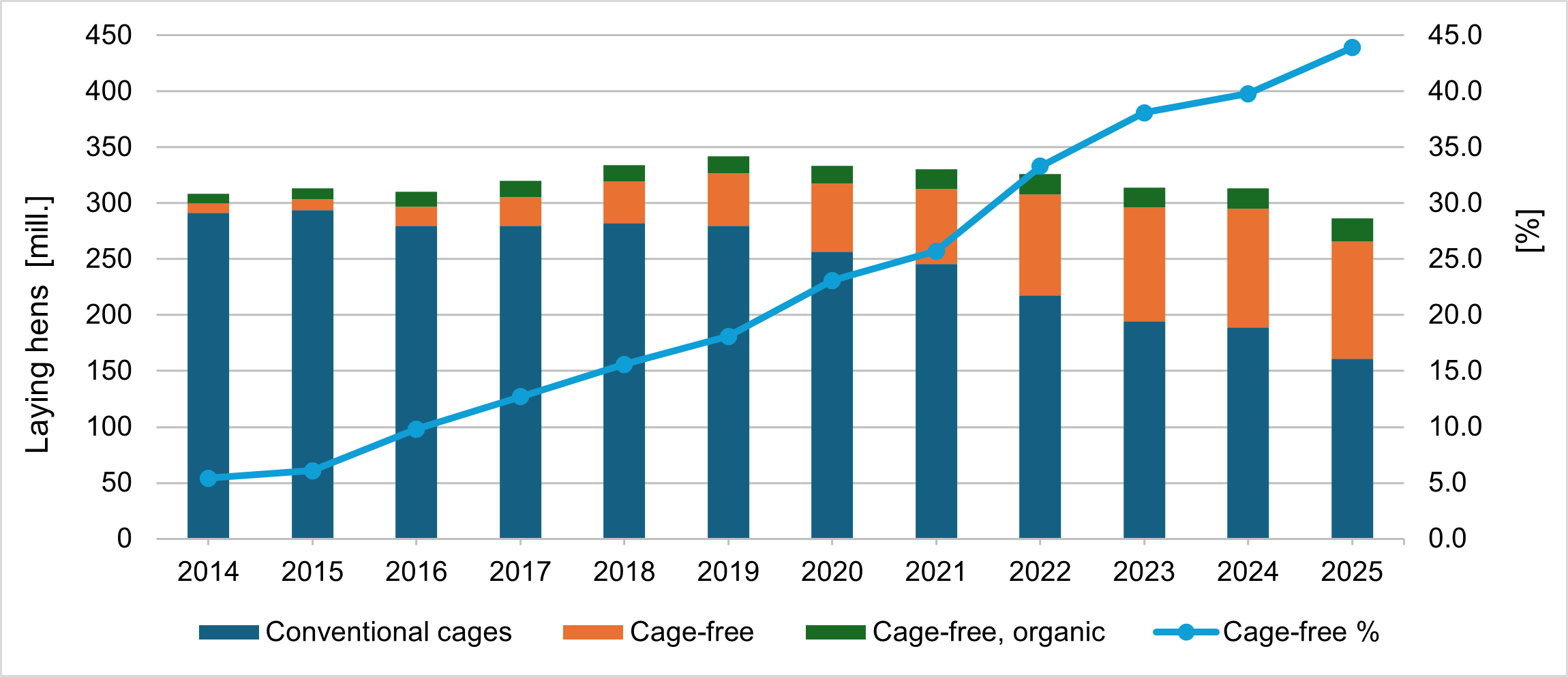

The highest number of laying hens in the analysed decade was reached in 2019 with 405.8 million, and the lowest in March 2025 with just 351.0 million. This fluctuation range was also evident among table egg layers. The highest value of 341.8 million was also recorded in 2019, the lowest value of 286.5 million in March 2025. Figure 1 shows the development of the laying hen inventory over the entire decade.

Design: A. S. Kauer based on data of the Egg Industry Center, Iowa State University.

The first major outbreak of AI in 2015 caught the poultry industry completely unprepared. It claimed the lives of 40.6 million laying hens, either through infection or preventative culling. As a result, between December 2014 and June 2015, the number of hens fell from 316 million to 275 million1. At the same time, the per capita egg consumption decreased from 263 to 256 pieces, a consequence of the sharp rise in prices due to the supply shortage. By 2019, inventories and table egg production had risen sharply. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a significant increase in the per capita consumption to 293 eggs, because many restaurants and canteens in schools and universities were closed and more meals were prepared in private households. With the end of the pandemic, demand and inventories decreased. With the second massive AI outbreak in 2022, the decline in the hen inventories continued. In total, over 40 million hens died from the disease or were killed as a preventive measure. In June 2022, a first low was reached with only 303 million table egg layers. Although a new wave of outbreaks in the following year was not as drastic as the previous two, it nevertheless resulted in a further decline in hen flocks, which continued into the middle of 2024 due to the reluctant repopulation of the barns. A joint letter from the poultry industry to the Secretary of Agriculture in July 2024 emphasized the critical economic situation in view of the high animal losses and a strategic plan to combat the highly pathogenic AI was called for2.

Source: APHIS.

The farms had barely recovered from the outbreaks when the fourth epidemic in a decade began in October 2024. It led to the highest losses ever with over 50 million laying hens. From March 2024 to March 2025, the number of table egg layers fell by 11 million to just 283.3 million, the lowest level in over a decade. Production declined by around 6 billion eggs since 2019. The resulting shortage in the food retail sector led to an unprecedented price increase and made egg imports necessary in order to secure the population’s supply. Per capita consumption fell to just 271 eggs in 2024 due to the high prices. The decline in table egg layers continued until mid-2025, in June only 271.3 million hens were counted, and egg prices in food retail remained on a high level. Protests among the population made it necessary for the government to intervene. This will be discussed in a later section.

Changes in the spatial pattern

In the decade under review, the spatial pattern of laying hen husbandry has changed significantly. The reasons for the relocation of production are, on the one hand, the high animal losses caused by the four AI epidemics and, on the other hand, changes in the housing systems of laying hens. Some of the leading companies have reduced flocks kept in conventional cages and converted existing barns to cage-free facilities or built new farms in locations with a lower risk of an AI infection. For example, Rose Acre Farms built two large farm complexes in Arizona in 2018 and 2024, each with more than 2 million hen places, far away from other laying hen farms. In 2022, Cal-Maine Foods converted a farm with 1.1 million places from conventional cages to floor management (large aviaries) and built another new farm for 2.2 million hens in Delta (Utah) (Windhorst 2018, 2023).

The four AI epidemics differed as well in their timelines as in their spatial dissemination. Iowa was primarily affected in 2015; Iowa and Nebraska in 2022; Ohio, California and Iowa in 2023; and California, Ohio and Iowa again in 2024/25. The flyways favoured by the wild birds, which were infected with the AI virus, were decisive for the spatial and temporal dissemination of the epidemics3.

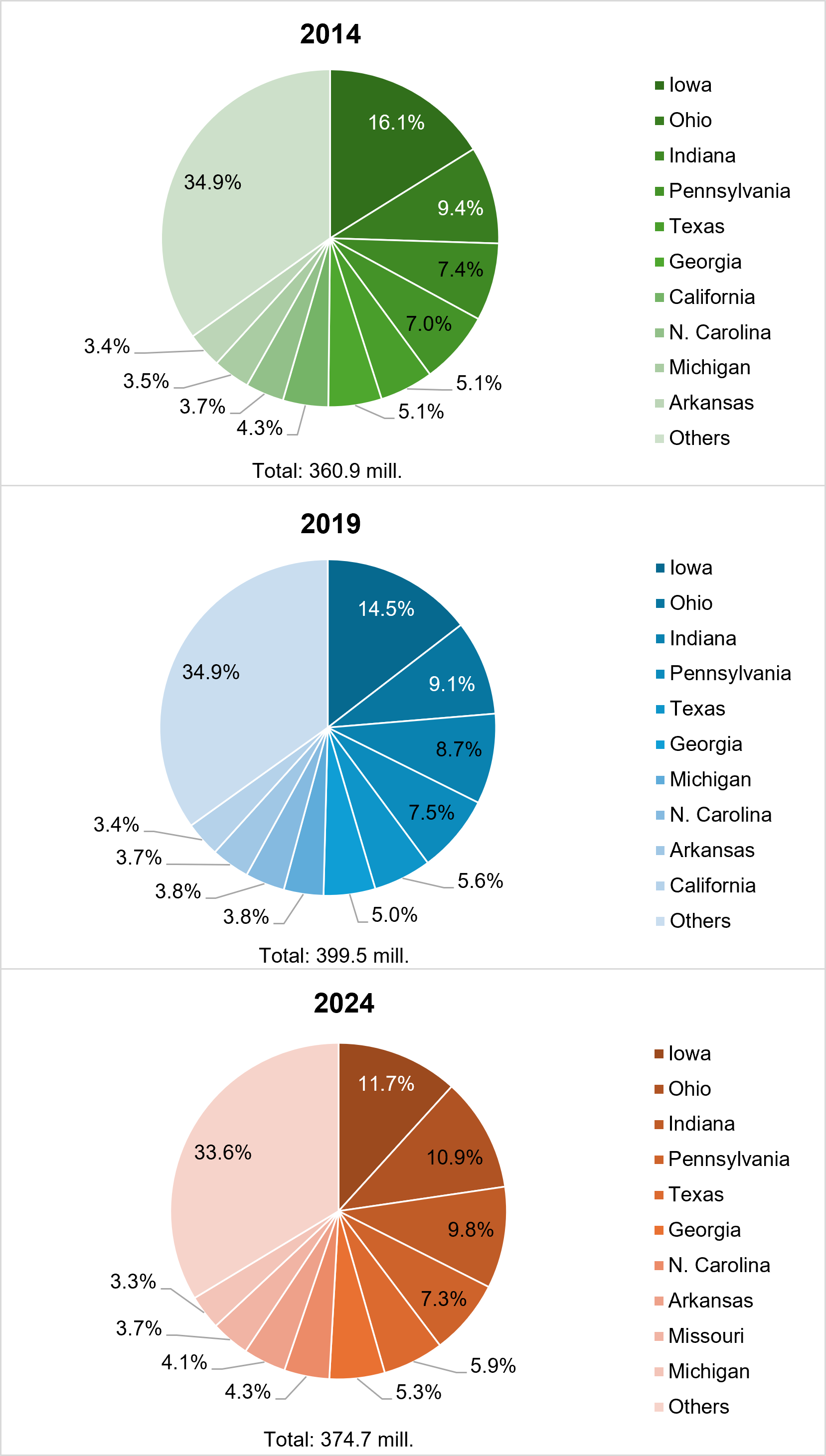

A comparison of the ten leading states in their laying hen inventories in 2014, 2019 and 2024 shows (Figure 2) that Iowa lost its dominant position. Between 2014 and 2024, the number of laying hens fell from 59.2 million to 43.8 million, or by 26.0%. The share in the total U.S. hen inventory fell from 16.4% to 11.7%. In contrast, the number of hens in Ohio rose from 29.1 million to 40.7 million, or by 39.2%, and the state’s share in the total inventory increased from 8.1% to 10.8%. Indiana showed a similar dynamic. The big loser was California, whose share in the U.S. table egg layer inventory declined from 2.7% to just 1.4% between April 2014 and April 2024. Like Ohio, California was particularly hard hit by the 2024/25 epidemic. Between April 2024 and April 2025, California lost 4.1 million table egg layers and is no longer one of the leading states. It will take several years to rebuild the flocks. Whether the previous status can be achieved again is an open question.

Design: A. S. Kauer based on USDA, NASS data.

On the road to cage-free farming

The ongoing and initially very controversial debate about the ban on conventional cages for laying hens, which began in 2008 with Proposition 2 introduced by the Humane Society of the United States in California, will not be discussed in detail here (see Windhorst 2009). In the following years, further propositions were put to the vote and in 2012 Proposition 12 was approved in a referendum. Despite initial resistance and a very hesitant abandonment of conventional cages, the conversion to or construction of cage-free facilities gained momentum. The decisions of leading food retailers, hotel chains and egg processing companies to only sell or use cage-free eggs played an important role. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the AI epidemics, the switch to cage-free production accelerated. While only 16.1 million or 5.4% of laying hens were kept in cage-free systems in 2014, this value has already reached around 126 million or 43.9% by mid-2025 (Figure 3). It can be assumed that two thirds of all laying hens will be housed in cage-free systems by 2030. The emerging legislation regarding financial compensation for farms following an AI outbreak and the associated animal losses may also play a decisive role here.

Design: A. S. Kauer, based on data of the Egg Industry Center, Iowa State University.

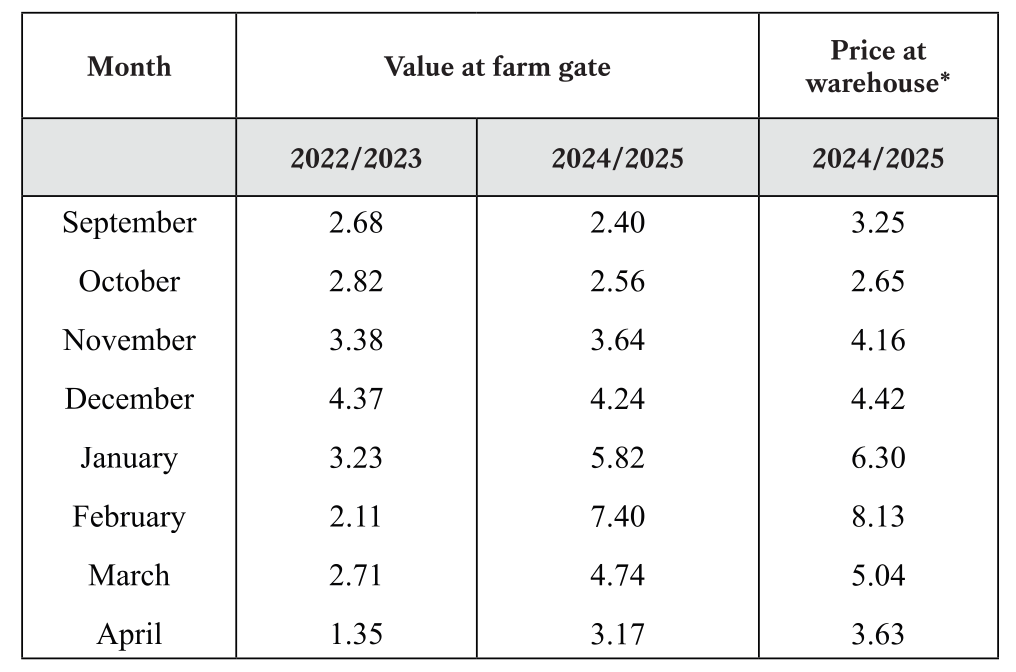

Egg shortage, rising prices and imports

Each of the four AI epidemics led to a sharp drop in egg production. As a result, the revenues of farms that were not affected by AI rose significantly. Prices did not stabilise until the farms were repopulated, but in most cases remained above the initial level for several months (Table 2).

Source: Egg Industry Center, Iowa State University.

*media del Midwest

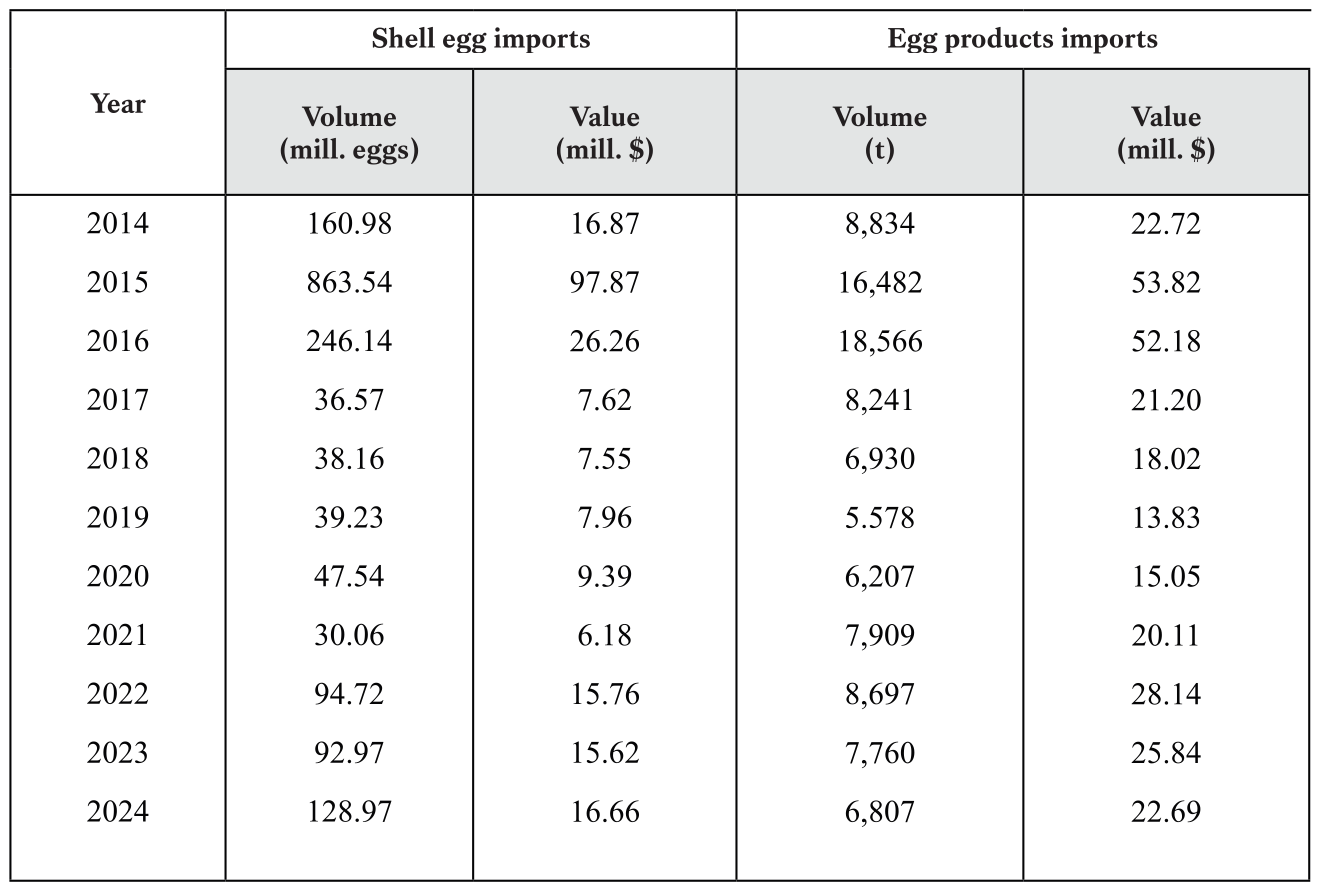

In the urban agglomerations of the north-east and in California, retail prices were at times as high as $10 a dozen. This led to protests among the population and forced the government to react. The egg products industry in particular had problems delivering the quantities it had contracted for because it was unable to obtain the eggs it needed, or could only do so at a much higher price. Like some grocery chains, it pushed to import eggs in order to be able to continue producing at a cost-covering level. Because the AI outbreak in 2015 caught laying hen farmers unprepared, the supply deficit was particularly high. Between the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, over 1.1 billion eggs worth $124 million and 35,000 t of egg products worth $106 million were imported. Although imports were lower regarding the volume after the epidemics of 2022 and 2023/24, they reached a total value of $124.7 million (Table 3).

Source: USDA, FATUS GATS.

The government responds

In December 2024, APHIS published a new guideline that ties future compensation payments for animal losses as a result of an AI infection to certain conditions5. For example, it requires that a farm may only be repopulated after a depopulation if it has been proven that biosecurity has been improved. This will be verified by an APHIS audit. The new legal regulation should lead to an improvement in biosecurity6.

On 18 February 2025, a group of 16 senators from both parties wrote to the Secretary of Agriculture calling for the development of a forward-looking strategy for the production of vaccines and their use in laying hen and turkey farming. In addition, negotiations should be entered into with trading partners to convince them of the need to vaccinate poultry flocks without the vaccination hindering or preventing trade7.

In response, the U.S. Department of Agriculture made $100 million available in April to enable scientists to develop new vaccines to protect poultry flocks and to research the spread of the AI virus in wild birds and its spread in flocks. This should, if not completely prevent recurring epidemics, at least limit their extent. In addition, $500 million for biosecurity measures and $400 million in financial relief for affected farmers were announced in a strategic plan8.

In March 2025, a working group consisting of representatives from the poultry industry, trade organisations and state veterinarians was installed. Its task is to draw up a plan for the vaccination of poultry. It was published in July 2025 and sent to the USDA and the organisations of the poultry industry for comments9. So far, no results are available. Egg producers hope that the broiler and turkey industry will give up their resistance to vaccination, which they have been justifying since 2014 with fears that leading consumer countries would stop imports.

Summary and perspectives

Four epidemics of the highly pathogenic avian influenza have affected poultry farmers in the USA over the past decade. In total, the 1,043 outbreaks on commercial farms resulted in the loss of over 221 million birds due to infection or preventative culling, including 178.8 million laying hens. The high economic losses suffered by farms and the processing industry as well as supply problems for the population forced the government to take action.

In addition to providing research funding for the development of vaccines, a plan for preventative vaccination is to be drawn up and will hopefully be adopted in consultation with the poultry industry.

Data sources and additional literature

Congressional Research Service. (2025). The highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in poultry, 2022–present. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R48518/R48518.1.pdf

United Egg Producers. (n.d.). Facts & stats. Retrieved from https://unitedegg.com/facts-stats

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA FAS). U.S. foreign agricultural trade. Retrieved from https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx?publish=1

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA NASS). (2024). Chicken and eggs annual summary 2024. https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/1v53jw96n/4b29d373g/4455b918n/ckegan25.pdf

U.S. Poultry & Egg Association. Economic data. Retrieved from https://www.uspoultry.org/economic-data

Windhorst, H.-W. (2009). Impacts of the California referendum on banning cages and perspectives for the U.S. egg industry. Zootecnica International, 31(2), 12–23.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2015). Avian influenza outbreaks in Iowa layer farms and their economic impacts. Zootecnica International, 37(12), 28–35.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2018). The USA on their way to cage-free egg production: The Lone Cactus egg farm in Bouse (Arizona). Zootecnica International, 40(2), 16–19.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2022). A new milestone in US egg production. Poultry World, 38(9), 26–28.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2022a). Verheerender Seuchenzug im Land: Eine räumliche und zeitliche Analyse der Aviären Influenza in den USA im Jahr 2022. Fleischwirtschaft, 102(9), 23–27.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2023). 2022 war Vieles anders: Eine Dokumentation und Analyse des AI-Seuchenzuges in den USA. Fleischwirtschaft, 103(4), 42–46.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2024). Third avian influenza outbreak in the USA within 10 years: The 2023–2024 epidemic. Zootecnica International, 46(9), 28–33.

Windhorst, H.-W. (2025). Fourth AI epidemic in the USA in the past decade: The epidemic in winter 2024/25. Zootecnica International, 46(7–8), 22–27.

Notes

1 The figures include table egg layers and parent stock.

2 https://www.uspoultry.org/position-papers/docs/HPAI-StrategicInitative.pdf

3 Windhorst 2015, 2022a, 2023, 2024, 2025.

4 https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_12,_Farm_Animal_Confinement_Initiative_(2018)

5 https://www.aphis.usda.gov/print/pdf/node/7419