Intestinal health serves as a baseline for raising healthy turkeys. Any compromise to the intestinal health negatively impacts the growth and production of turkeys and adversely affects their profitability. Coccidiosis in turkeys is caused by Eimeria species which pose a substantial risk to the turkey industry. Turkey coccidiosis is controlled by feed administration of anticoccidials and phytogenic products or vaccination of turkey poults.

Vijay Durairaj1, Steven Clark2 , Emily Barber1 and Ryan Vander Veen1

1 Huvepharma, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

2 Huvepharma, Inc., Peachtree City, Georgia, USA

Corresponding author: Vijay.Durairaj@huvepharma.us

Seven Eimeria species have been described in turkeys and each Eimeria species targets specific regions of the intestine. In field conditions, turkeys consume sporulated oocysts in the litter, which replicate and then numerous unsporulated oocysts are shed in the feces. The oocysts shed in the feces may be screened at regular intervals to monitor the oocyst load in turkey barns. Surveillance of Eimeria species in the turkey flock helps in understanding the oocyst load as well as to speciate the circulating strains on farm premises. In February 2023, an increased number of oocysts were detected in 30-day-old turkeys raised in two conventional barns (Barn A and B), USA. As a part of the field investigation, a few turkeys were necropsied and studied. Although gross lesions were noticed in few birds from Barn A, most of the turkeys in both barns did not have any gross lesions associated with coccidiosis. On mucosal scraping, Eimeria oocysts were detected in both barns and confirmed as E. meleagrimitis by PCR and sequencing.

Introduction

Maintaining intestinal integrity is one of the top goals for raising health turkeys. Coccidiosis is a common protozoal disease impacting intestinal health. Eimeria species are non-flagellated protozoan parasites that are ubiquitous in intense poultry rearing operations and is the causative agent for coccidiosis. Eimeria species are host specific in nature and seven Eimeria species have been described in turkeys. The seven Eimeria species include E. adenoeides, E. meleagrimitis, E. gallopavonis, E. dispersa, E. meleagridis, E. innocua and E. subrotunda. Each Eimeria species affects specific parts of the intestine, undergoes replication, and induces inflammation, necrosis and damage to the intestine. The intestinal inflammation adversely affects the integrity of the intestine and interferes with normal absorption of nutrients, predisposes to secondary infection, and opens a channel for the entry of the intestinal microbiota to cross the barrier and enter the host system.

Coccidiosis is spread by fecal-oral route. Turkeys infected with Eimeria shed the non-sporulated oocysts in the litter, which are non-infectious. Under optimum temperature, moisture and oxygen levels, the non-sporulated oocysts sporulate and become infectious. Turkeys consuming the sporulated oocysts becomes infected with that Eimeria species and the cycle continues. Turkey Eimeria species are prolific in nature and reproduce very quickly with a prepatent period between 4-5 days. Not all the turkeys are exposed to Eimeria at same level, it varies depending on Eimeria oocyst load in the litter as well as the management conditions. The Eimeria oocyst load could be impacted by the density of birds, season, litter management, downtime period and the immune status of turkeys.

The turkey industry follows prophylactic administration of anticoccidials, vaccination or administration of phytogenic products to control coccidiosis. Compared to the chicken industry, the turkey industry has a limited number of anticoccidials. Rotation or shuttle programs are followed by the turkey industry as an intervention strategy to prevent coccidiosis. In rotation programs, different anticoccidials/phytochemicals are rotated between the seasons or anticoccidials/phytochemicals and vaccination are rotated between the seasons. In shuttle programs, the different anticoccidials/phytochemicals are changed between different age groups of turkeys. Due to the limited number of anticoccidials available, there are increased chances of repeating the same anticoccidials which further increases the chance of resistance against these anticoccidials.

Coccidiosis poses a threat to the turkey industry and was ranked #9 in the 2022 US turkey industry survey. The economic losses from coccidiosis are not limited to losses associated with mortalities, but also include poor feed conversion ratio (FCR), production losses, and treatment costs. The intestinal damage incurred by Eimeria predisposes birds to secondary infection resulting in further economic losses. To avoid these losses, several turkey production companies routinely follow coccidiosis surveillance programs to monitor the Eimeria strains circulating on their farm. Since infected turkeys shed oocysts in the feces, oocyst per gram (OPG) is used as a monitoring tool to understand the Eimeria load in the barn and evaluate the anticoccidial or vaccine efficacy.

Case report

Case history

In February 2023, enteritis was reported in 30-day-old-turkeys in Southeast, USA. Out of five barns, two barns (A and B) were affected and each barn had 17,761 turkeys on the day of placement. The poults were placed on new litter shavings and in-feed medication was used for coccidiosis control. The routine coccidiosis monitoring program detected an increased number of oocysts. At 30 days-of-age, necropsy was performed on a few runted birds and examined for gross lesions.

Evaluation of mucosal scrapings

The intestinal mucosal scrapings (duodenum, jejunum, ileum and ceca) were collected from the birds/ barn and pooled separately. The mucosal scrapings were examined under the microscope.

DNA extraction and PCR

DNA was extracted from the mucosal scrapings by using glass beads to rupture the oocysts followed by proteinase K (Qiagen) digestion. The DNA extraction was performed by using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Kit (Qiagen) by following the manufacturer recommendations. Each PCR reaction mix (25 µL) had 5 µL of the template along with 1x GoTaq® G2 Hot Start Master Mix (Promega) and 0.4 µM of each primer.

Gel electrophoresis and sequencing

The amplicons (2 µl) generated from the PCR reactions were electrophoresed and visualized in E-GelTM EX Agarose Gels, 2% (Invitrogen). A reference E-Gel™ 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (Invitrogen) was used to identify the size of the amplicons. The amplicons were purified following the instructions using a using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) followed by submission for sequencing (Eurofins, KY).

Results and discussion

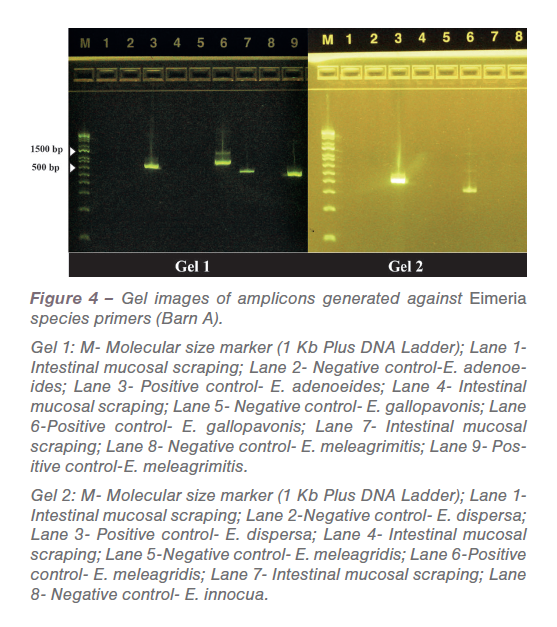

Overall, most of the turkeys examined in both barns did not have any gross lesions associated with coccidiosis. Only a few turkeys in Barn A had abnormal contents with fluid and mucoid contents in the duodenum and jejunum (Figure 1).

Overall, most of the turkeys examined in both barns did not have any gross lesions associated with coccidiosis. Only a few turkeys in Barn A had abnormal contents with fluid and mucoid contents in the duodenum and jejunum (Figure 1).

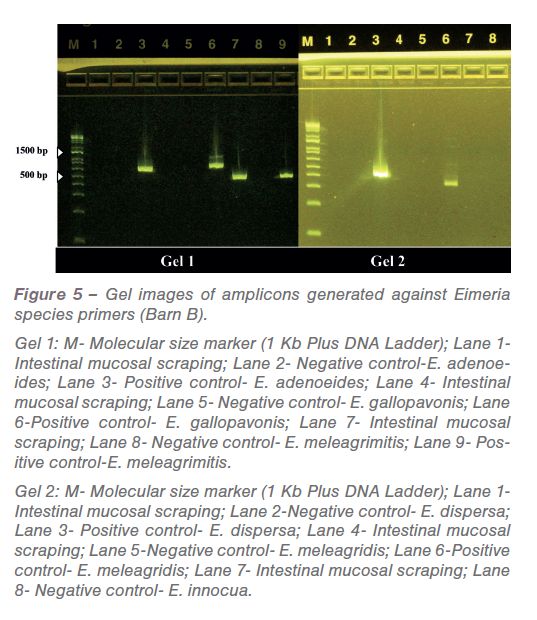

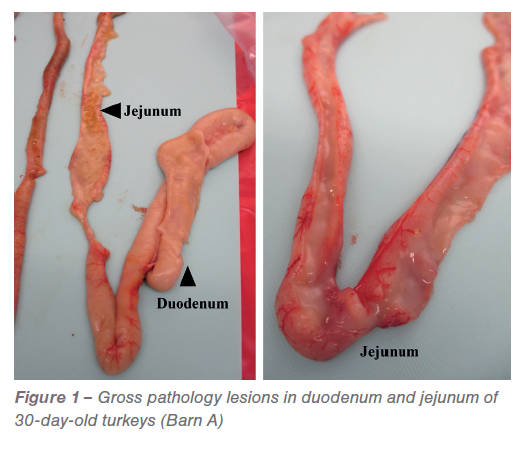

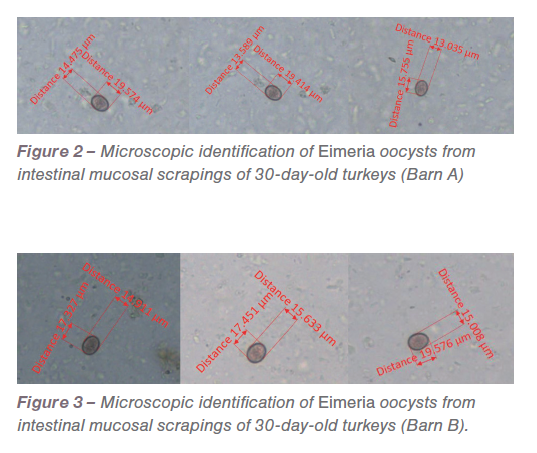

On evaluation of the intestinal mucosal scrapes, Eimeria oocysts were detected in both barns (Figures 2 and 3).

In low-grade infections the pathological manifestations are not pronounced. Also, in field conditions all turkeys are not challenged at the same time and the dose varies based on oocyst consumption. PCR was performed against common turkey Eimeria species based on previously published primers. The amplicons generated from PCR reactions (Figure 4 and 5) were sequenced, analyzed and confirmed as E. meleagrimitis.

In low-grade infections the pathological manifestations are not pronounced. Also, in field conditions all turkeys are not challenged at the same time and the dose varies based on oocyst consumption. PCR was performed against common turkey Eimeria species based on previously published primers. The amplicons generated from PCR reactions (Figure 4 and 5) were sequenced, analyzed and confirmed as E. meleagrimitis.

The upper small intestine of turkeys is the target organ for protozoan parasites E. meleagrimitis, E. dispersa, E. subrotunda, and E. innocua. Among the Eimeria species, E. meleagrimitis is considered highly pathogenic, E. dispersa moderately pathogenic, while E. subrotunda and E. innocua are non-pathogenic.

The highly pathogenic species E. meleagrimitis targets the duodenum and upper jejunum and induces severe damage to intestinal mucosa resulting in inflammation, congestion, and edema. The normal intestinal contents are replaced with watery, mucoid, fibrinous contents and diphtheritic membrane in severe infections. The clinical signs include ruffled feathers, drooped wings, listlessness, unthriftiness, huddling and foul-smelling watery or mucus diarrhea, which may be stained with blood and appear brownish or red in color. In subclinical infections these clinical manifestations are not present. Production performance is affected in both subclinical and clinical infections, while increased mortality rates result from heavy infections.

In field conditions, coccidiosis has not been reported in birds less than 10 days of age as it takes a few rounds to cycle and infect the birds. Diagnosis of clinical coccidiosis in turkeys could be accomplished based on the clinical signs, gross pathology lesions, mortalities, microscopic evaluation of Eimeria oocysts, PCR and sequencing. However, diagnosis of subclinical coccidiosis is often challenging without any clinical manifestation, gross pathology lesions or mortalities. Subclinical coccidiosis is a persistent problem in the turkey industry. Subclinical coccidiosis causes poor FCR and affects the production performance of turkeys in terms of body weight gain.

Thus, in commercial turkey production facilities, routine monitoring of OPGs helps to understand the Eimeria oocyst load in the flock. Gross pathology lesions, evaluation of mucosal scrapings, PCR and sequencing confirmed the presence of E. meleagrimitis in this case. Thus, coccidiosis surveillance programs help in understanding the Eimeria field pressure and circulating field strains, which in turn provides more insights in understanding the efficacy of anticoccidials and vaccines.

References

1. Cervantes HM, McDougald, LR, Jenkins MC. Coccidiosis. In: Swayne D, Boulianne, M, Logue C, McDougald L, Nair V, Suarez D, deWit S, Grimes T, Johnson D, Kromm M, et al., editors. Diseases of poultry. 14th ed. Ames (IA): Wiley-Blackwell. p. 1193–1216; 2020.

2. Chapman HD. Coccidiosis in the turkey. Avian Pathol. 37:205-223; 2008.

3. Clark SR, Frobel L. Current Health and Industry Issues Facing the US Turkey Industry. Proceedings 126th Annual Meeting of the USAHA, Virtual; Committee on Poultry and Other Avian Species. Pending Publication. Presented Oct 3, 2022.

4. Gadde UD, Rathinam T, Finklin MN, & Chapman HD. (2020). Pathology caused by three species of Eimeria that infect the turkey with a description of a scoring system for intestinal lesions. Avian Pathol. 49:80-86.

5. Hafeez MA, Shivaramaiah S, Dorsey KM, Ogedengbe ME, El-Sherry S, Whale J, Cobean J, Barta JR. Simultaneous identification and DNA barcoding of six Eimeria species infecting turkeys using PCR primers targeting the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) locus. Parasitol Res. 114:1761-1768. 2015.

6. Imai RK, Barta JR. Distribution and abundance of Eimeria species in commercial turkey flocks across Canada. Can Vet J. 60:153-159. 2019.

7. Lund, E.E, & Farr, M.M. (1965). Coccidiosis of the turkey. In H.E. Biester & L.H. Schwarte (Eds.), Diseases of Poultry, 5th ed., (pp. 1088-1093). Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press.