Fertilisation and a fertile egg marks the beginning of a new life but is by no means a guarantee of a long life, as the embryo journey is full of obstacles. Stress, genetic factors, diseases or nutritional deficiencies may all kill the embryo before the egg is laid.

The newly laid fertile egg is then exposed to another set of risks: the conditions under which it cools down from the hen’s body temperature to the ambient conditions in the nest, the time this takes, mechanical factors, chemicals, infections and even disinfection are all hurdles to overcome. After that come storage, transport and the start of incubation – not always conducive to survival of fertile eggs and embryos.

These kinds of very early mortality are almost impossible to identify in a standard, industrial way – by candling. As a consequence, the ‘clears’ category contains both eggs that are truly infertile and those that contain early-dead embryos. The only way to distinguish truly infertile from early-dead eggs is by breaking them out for analysis. However, to diagnose accurately and thus choose the correct solution, it is essential to be able to distinguish between these two groups.

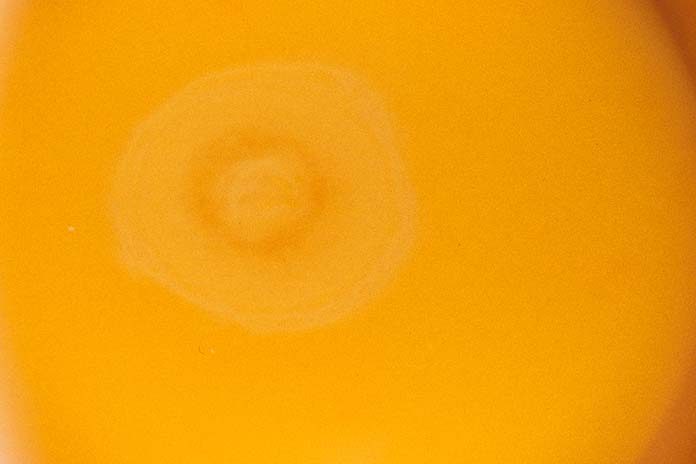

The presence of a tiny ring on the surface of yolk, just 3-4 mm in diameter – visible immediately after oviposition – allows to the egg to be classified as fertile. The embryo continues to develop as the egg cools down. During an optimum cooling time – 6 hours – it will grow to a diameter of about 5 mm and become storage resistant. This is stage XII-XIII, when the ring is still small and its centre clearly yellow. The colour of the yolk surrounding the embryo remains unchanged. Too slow cooling, or high storage or transport temperatures cause the embryo to develop more. Increased diameter of the ring, its centre filled up with white cells, and a pale yolk zone surrounding the embryo indicate continued development and absorption of water from the albumen.

These embryos have developed beyond the storage-resistant stage and will probably die if placed in the low temperatures used for storage.

Life continues, and the start of incubation of fertile eggs brings further changes. After just 24 hours, the pale-yellow yolk zone surrounds the embryo.

After 48 hours, that zone has increased, and a small island of blood vessels can be seen with a magnifying glass or under the microscope. By 60 hours, the vessels have developed and soon a blood ring can be seen with the naked eye. The development of the vessels is a reliable indication that the egg is fertile. But be careful: traces of blood found in an egg that has not been incubated are not necessarily a reliable sign of ‘life’. Meat or blood spots – released in the hen’s oviduct – can be found even in infertile table eggs.

Analysis of ‘clears’, done by candling at 7-10 days, provides reliable information. Candling earlier than this makes no sense. Changes in yolk colour, or cloudy yolk in an apparently ‘clear egg’ can be interpreted as an expression of very early mortality. The more advanced phases such as ‘blood ring’ or ‘black eye’ leave no doubts. If a break-out is done later on – for example at transfer – indicators of very these early mortality are less visible and mistakes easier to make, as the yolk membrane becomes weak and breaks easily.

Advice:

- Practise distinguishing between ‘fertile or not’ on fresh eggs that have not yet been incubated.

- Check the stage of embryo development by measuring diameter and assessing appearance when eggs arrive. Use this information to decide on cooling, on-farm storage and transport.

- If % of ‘clears’ is cause for doubt, shift candling to days 7-10 to get a clearer picture.