In Italy, several tons of sea urchins are harvested annually, yet only the gonads are used for consumption; the rest, rich in calcium carbonate, is discarded. A study by the University of Milan explored the potential of these residues as an alternative calcium source for laying hens. The findings reveal that incorporating sea urchin-derived calcium does not compromise either egg production or egg quality while enhancing certain animal welfare indicators. This approach offers a promising step towards more sustainable and eco-friendly livestock farming.

Introduction

Around 3,000-3,500 tons of Paracentrotus lividus sea urchins are harvested annually from the Mediterranean Sea for human consumption (FAO, 2017; Stefansson et al., 2017). Italy is the main consumer among European countries, with 30 million individuals collected each year (Guala et al., 2018). However, only 10–30% of the urchin’s weight — the gonads — is eaten, leaving the rest, mainly the skeleton (test and spines), as waste (Marzorati et al., 2021). As noted by several researchers, this type of waste is neither environmentally sustainable nor economically advantageous (Garau et al., 2012). Considering that sea urchin tests and spines contain high amounts of minerals, primarily calcium carbonate (calcite) with a significant percentage of magnesium carbonate (Varkoulis et al., 2020), they could serve as a valuable feed ingredient for laying hens, which need these minerals for egg production. Calcium is crucial in the diet of laying hens for their metabolism and bone development. Eggshell consists of 94–97% calcium carbonate in calcite crystals (Kristl et al., 2019). Magnesium, the second most abundant mineral in the eggshell in the form of magnesium carbonate, is essential for eggshell strength and thickness (Kim et al., 2013).

Traditionally, the main source of calcium in poultry feed is non-biogenic, coming from limestone, which varies in bioavailability and digestibility (Cufadar et al., 2011). By contrast, in recent years, biogenic minerals have proven to be more bioavailable and effective at lower doses, as they are more efficiently absorbed and retained by animals, reducing mineral excretion into the environment (Webster et al., 2004).

Experimental study

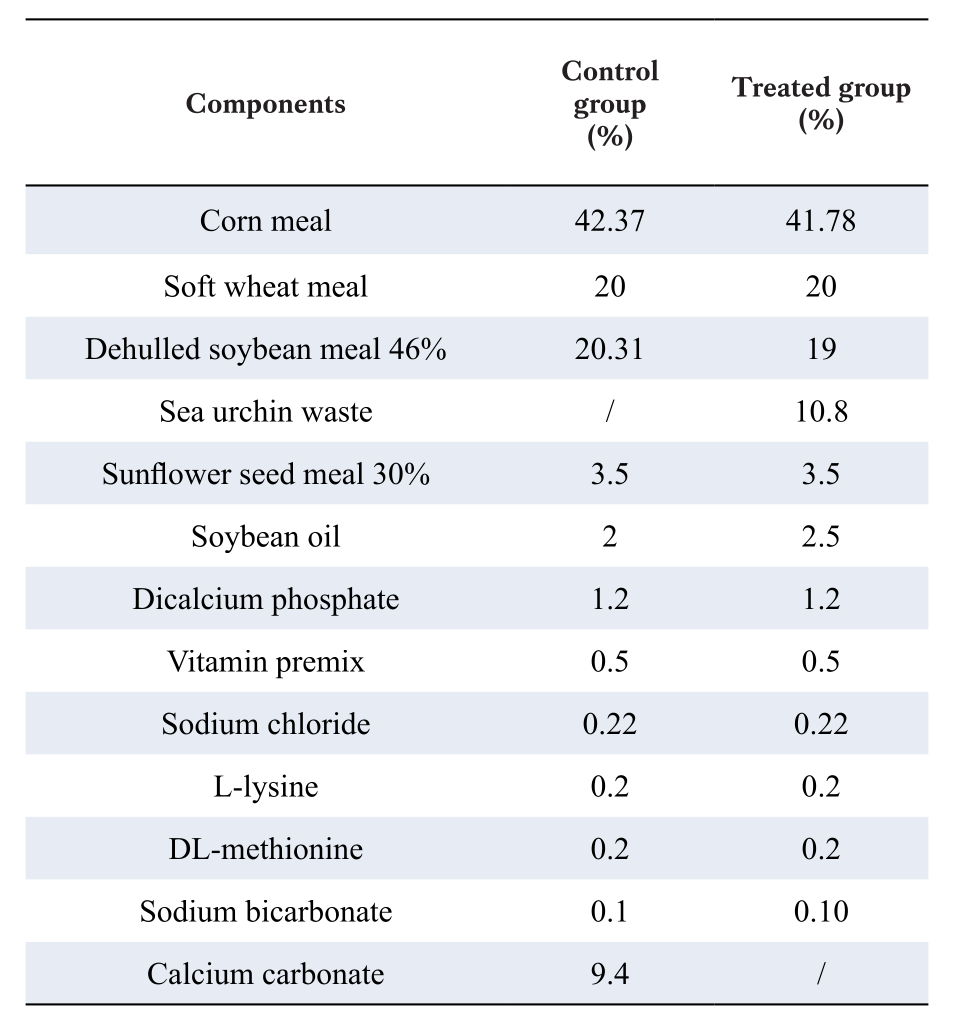

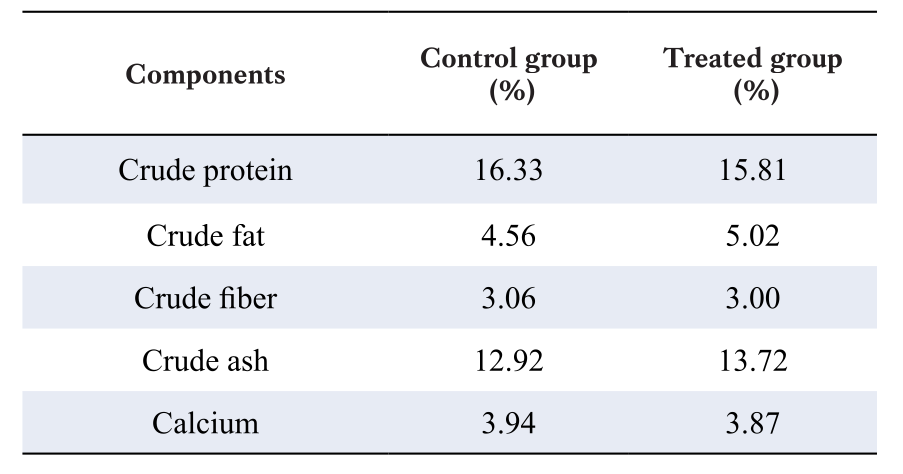

Following a circular economy model, where a waste becomes a resource, researchers at the University of Milan evaluated the use of sea urchin-derived calcium as a limestone-derived calcium substitute in laying hens’ diets. For the study, they collected 400 kg of waste from small processing companies and restaurants in Sardinia, Sicily and Apulia. After heat-treating the material at 80 °C for 30 minutes and then grinding it, they incorporated it into pellets for the treated group of hens. A control group received an isonutritive commercial diet. The two formulations contained similar calcium content (≈ 3.9%), as reported in Tables 1 and 2. The study involved 128 Hy-Line Brown hens, monitored from 19 to 52 weeks of age, with assessments of productive parameters, egg quality and animal welfare.

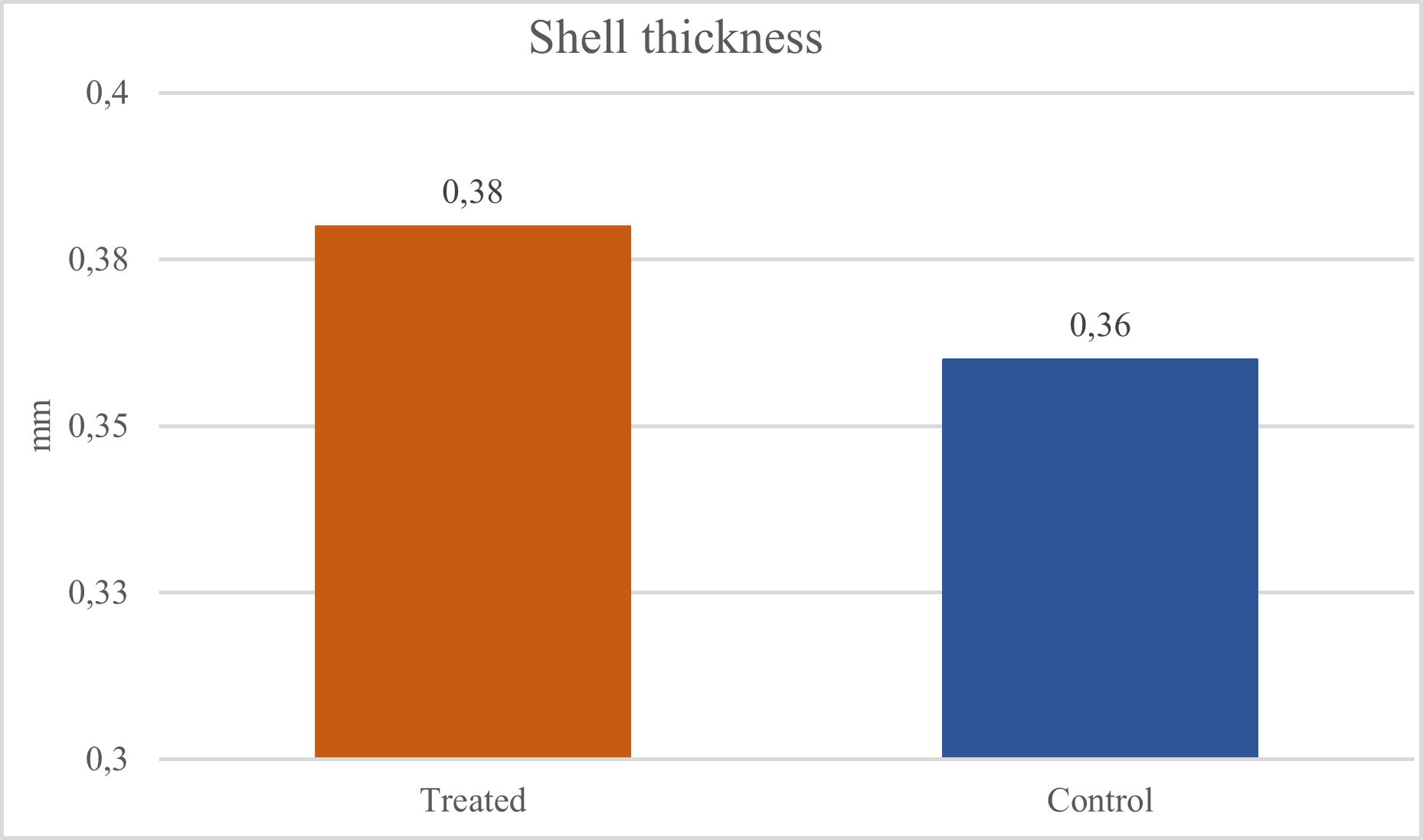

Egg production or egg size (category M) showed no significant differences between groups. However, hens receiving sea urchin-derived calcium recorded a lower percentage of discarded eggs (2.10% vs. 2.38%), suggesting a positive effect of sea urchin-derived calcium. Moreover, the eggs produced by the treated group had thicker eggshells (average: 0.38 mm vs. 0.36 mm), as shown in Figure 1. Despite the greater thickness, eggshell breaking strength and ultrastructure remained comparable. The absence of differences represents an excellent outcome for the purpose of the study, as it indicates the potential replacement of limestone-derived calcium with calcium obtained from sea urchin tests and spines.

Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (P <0.05).

Animal welfare was also assessed using the Welfare Quality® protocol, since a deficiency or imbalance of dietary minerals can lead to the spread of feather pecking, a multifactorial condition in which birds peck at the feathers of their conspecifics, occasionally escalating to cannibalism (Dixon, 2008). In this study, hens receiving the sea urchin–supplemented diet showed fewer lesions on the head, back and tail, especially at the end of the trial, along with healthier footpads.

To verify the correct utilization of calcium from the diet, and not from bone mobilization, researchers checked keel bone deviation according to Welfare Quality® guidelines and tibia breaking strength. The tibia, a bone rich in medullary bone tissue, supplies calcium for eggshell formation if dietary intake is deficient or unavailable (Bryden et al., 2021). No significant differences were found between the two experimental groups, indicating correct absorption and utilization of sea urchin calcium.

Conclusions

Conclusions

Repurposing sea urchin waste as a source of calcium for laying hens reflects a more forward-thinking, sustainable vision of Italian livestock farming. The study demonstrates that replacing limestone-derived calcium with sea urchin-derived calcium preserves animal welfare, production and egg quality, while improving some indicators. The similarity between the two study groups supports the substitution’s viability, although further research is needed to test these results across varying farming conditions and to evaluate their long-term effectiveness over longer production cycles. Nevertheless, this research paves the way for the concrete possibility of developing a niche, more eco-conscious supply chain, turning fishery by-products into a valuable poultry feed resource.

References

Bryden, W. L., Li, X., Ruhnke, I., Zhang, D., & Shini, S. (2021). Nutrition, feeding and laying hen welfare. Animal Production Science, 61(10), 893–914. https://doi.org/10.1071/an20396

Cufadar, Y., Olgun, O., & Yildiz, A. Ö. (2011). The effect of dietary calcium concentration and particle size on performance, eggshell quality, bone mechanical properties, and tibia mineral contents in moulted laying hens. British Poultry Science, 52(6), 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2011.641502

Dixon, L. (2008). Feather pecking behaviour and associated welfare issues in laying hens. Avian Biology Research, 1(2), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.3184/175815508X363251

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2017). Fisheries and aquaculture statistics 2015: Yearbook. Rome, Italy: FAO. https://www.fao.org/fishery/static/Yearbook/YB2015_CD_Master/booklet/web_I7989T.pdf

Garau, G., Castaldi, P., Deiana, S., Campus, P., Mazza, A., Deiana, P., et al. (2012). Assessment of the use potential of edible sea urchins (Paracentrotus lividus) processing waste within the agricultural system: Influence on soil chemical and biological properties and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and wheat (Triticum vulgare) growth in an amended acidic soil. Journal of Environmental Management, 109, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.05.001

Guala, I., Grech, D., Masala, M., Piazzi, L., Ceccherelli, G., Brundu, G., et al. (2018). Population monitoring of Paracentrotus lividus in the Tavolara Punta Coda Cavallo Marine Protected Area (Technical report). Torre Grande, Italy: Fondazione IMC–Centro Marino Internazionale ONLUS.

Kim, C. H., Paik, I. K., & Kil, D. Y. (2013). Effects of increasing supplementation of magnesium in diets on productive performance and eggshell quality of aged laying hens. Biological Trace Element Research, 151(1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-012-9537-z

Kristl, M., Jurak, S., Brus, M., Sem, V., & Kristl, J. (2019). Evaluation of calcium carbonate in eggshells using thermal analysis. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 138(4), 2751–2758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08678-8

Marzorati, S., Martinelli, G., Sugni, M., & Verotta, L. (2021). Green extraction strategies for sea urchin waste valorization. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8, 730747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.730747

Stefansson, G., Kristinsson, H., Ziemer, N., Hannon, C., & James, P. (2017). Markets for sea urchins: A review of global supply and markets. Skýrsla Matís, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12657.99683

Varkoulis, A., Voulgaris, K., Zaoutsos, S., Stratakis, A., & Vafidis, D. (2020). Chemical composition and microstructural morphology of spines and tests of three common sea urchin species of the sublittoral zone of the Mediterranean Sea. Animals, 10(8), 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10081351Webster, A. B. (2004). Welfare implications of avian osteoporosis. Poultry Science, 83(2), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/83.2.184