Even if many people use the same methods or knowledge for water vaccination in cage or aviary systems as they do for broiler or breeder flocks raised on the floor or in free-range systems, this approach is completely wrong. To ensure that the vaccination is done properly for such a large number of birds, two things must be done right: proper preparation for vaccination and a clear understanding of the unused (unavailable) water remaining in the drinking lines.

Preparation for vaccination

When preparing to vaccinate a large number of birds, proper preparation is absolutely critical. Any mistakes at this stage can be very costly—not only due to wasted vaccine but also because of potential health problems in the flock later. Poor vaccination leads to uneven immunity, increased disease risk, and eventually a significant loss in productivity and profit.

-

General requirements before vaccination

Unit managers must ensure that birds have the standard live body weight appropriate for their age, with uniformity across the flock and are evenly distributed in cages and across tiers.

Accurate and complete data must be available for vaccine volume calculation; this includes stocking density, total bird count, and average water consumption. Furthermore, no stress factors (for example feed or water disruptions, loud repair work, or environmental stressors) should affect the birds for 2–3 days before vaccination.

It should not be overlooked that weak birds must be culled, and small birds should be separated into dedicated cages. The poultry house must be in proper sanitary condition: manure and visible dirt should be removed thoroughly, but without using disinfectants just before vaccination.

Finally, all lighting systems (especially standby lighting at the start of the hall) must be working properly and clean protective clothing and footwear must be available in sufficient quantities for everyone working in the poultry house.

-

Unit managers must ensure the following during water vaccination

On the day before vaccination, strict compliance with all of the above items is necessary, along with full functionality of the water supply system (including water valves, pressure gauges, water meters, water filters, and the absence of leaks or sagging in the drinking lines). The availability of equipment for draining residual water from the ends of the drinker lines in the poultry house is also required, together with thorough cleaning of the water filter located inside the poultry house.

One must flush the drinking system (without using disinfectants) and ensure that birds are well hydrated according to actual water consumption data. Finally, the water supply should be turned off 30–60 minutes before the lights are switched off (based on the lighting schedule), and the end caps of the drinker lines must be opened to drain the remaining water.

During vaccination, the presence of operational staff in the poultry house is required to ensure safe and uninterrupted operation of the technical equipment.

After vaccination, operators must ensure that uninterrupted water flow resumes in the drinking system immediately once vaccination is completed, and that birds are not exposed to stress factors for at least 24 hours post-vaccination. These include feed or water supply disruptions, noisy repairs or construction work, and any other stress-inducing activities.

Finally, before the lights are turned off (according to the lighting schedule), the water supply must be shut off 30–60 minutes earlier, and the end caps on the drinker lines must be opened to allow complete drainage.

-

Do a fake vaccination the day before

To ensure that everything goes smoothly during the actual vaccination, a test run should be carried out one day in advance—this is often called a “fake vaccination”.

During this procedure, you do everything exactly the same as you would on the real vaccination day—but without the vaccine. Use only water + stabilizer + dye.

This test allows you to see how much mother solution (stock solution) is required to fully fill the drinking system; to measure the time needed to deliver the vaccine to the birds during daylight hours and to identify any technical issues with water flow, line priming, or flushing.

The stock solution should be divided into several smaller portions, each designed to be consumed by the birds within one hour.

This helps ensure that the vaccine reaches the birds before their drinking activity begins to drop off later in the day.

-

How to calculate the stock solution (mother solution)?

There are many ways to estimate the volume of stock solution needed, including official water consumption guidelines by bird age.

However, only a fake vaccination (test run) can reveal the actual water intake of your birds at their specific age and under real farm conditions.

Environmental factors, like season and temperature, time of sunrise and uncontrolled light exposure in the poultry house during system filling (for example, due to non-sealed ventilation can cause some birds to start drinking early consuming part of the vaccine before the lights officially come on) also affect how much stock is solution required.

-

How to calculate the stock solution per cage battery or strip of birds?

It’s simple math: after the fake vaccination, you’ll know the total volume of stock solution required. Just divide that total by the number of batteries or sections of birds to determine the required volume per battery or per group.

-

How to know if the stock solution was used correctly?

During vaccination, regularly check that the doser (Dosatron) or medicator is working correctly.

Track how much stock solution was used and compare this with the water meter reading.

For example: if you used 25 liters of stock solution and the dosing ratio is 1:100, then 2,500 liters of working solution should pass through the lines.

This helps confirm that the vaccine concentration remains consistent throughout the entire vaccination.

At the end, calculate the final usage percentage to ensure the accuracy.

-

How to calculate the vaccine dose?

It depends on the type of vaccine you are using. If the vaccine is high quality and reliable, simply take the number of doses needed for the population, adjusting slightly to account for residual water in the lines. Instead, if the vaccine’s effectiveness is questionable, it’s better to increase the number of doses slightly, and later verify the immunity level through blood tests and lab diagnostics.

Lights off: the golden rule of water vaccination when filling empty drinking lines if you’re working with commercial layers, breeders, or broilers in cage or aviary systems, there’s one golden rule that must never be ignored: always fill empty drinking lines with the lights off. Why? Because turning on the lights too early during vaccination causes birds near the Dosatron or light sources to drink too soon, leads to uneven vaccine intake with overdosing at the front and underdosing at the back, immediately reduces water pressure across the system, prevents the last batteries and top-tier cages from receiving the vaccine entirely, and ultimately results in poor flock immunity along with serious long-term health and economic losses. This is why the system must always be filled battery by battery, in the dark, just like during the fake vaccination.

Only when all lines are full and pressurized—then the lights go on, and the vaccination officially begins.

-

How to fill the drinking system with vaccine solution

Always fill the lines in darkness, especially near light leaks from fans or vents. This prevents birds from starting to drink too early. Then, fill the system battery by battery (cage row by cage row):

- start with one battery;

- as soon as you see blue-colored water (vaccine + dye) at the end of the line, shut off water flow to that battery;

- then move to the next battery;

- if your water pressure is strong, you may fill two batteries at a time, but never more.

Be careful with light leaks.

Some cages, especially the top tiers, may receive light from ventilation or gaps. Shut off water to those batteries first after filling to avoid early drinking.

If everything is well organized, filling all drinker lines should take no more than 45 minutes.

-

When does vaccination start?

Vaccination time starts only after all drinker lines are fully filled with vaccine solution and lights are turned on.

Water supply is turned on to all batteries simultaneously, this ensures all birds have equal access to properly dosed water. Use 1% dosing on the Dosatron during vaccination; depending on flock size, divide your stock solution into 2–3 batches. If you’re running out of time (birds start drinking less), you can increase the Dosatron setting to ensure all vaccine is consumed. But if you’ve prepared correctly, this should not be necessary.

-

Key insight from the fake vaccination

After conducting a proper fake vaccination, you’ll know how much total water is needed to fill your system, how much stock solution is required to fill all batteries and how many stock solutions you’ll need to continue vaccination once the lights are turned on.

So, during the real vaccination, use one stock solution to fill the entire drinking system in the dark, then prepare fresh stock solutions for the actual drinking phase, when birds are active and drinking under light.

-

A clear understanding of unused (unavailable) water remaining in the drinking lines: what it is and where it comes from

This is often where a big surprise occurs, even for people who think they know the system well.

If you’ve ever done a water vaccination, you’ll know exactly what this means. As soon as the vaccination starts, you’re standing at the end of the drinking line, watching the line, waiting for the first blue water to appear. But instead, clean, colorless water flowing from the open drinker cups. No blue. No vaccine. This is unavailable water, that is clean water that was already sitting inside the lines before the vaccine solution entered the system. It doesn’t contain any vaccine or dye. It comes from water sitting below the nipple level inside the pipe. Since the nipple usually enters about 10 mm into the pipe, any water below that point is unreachable (birds simply cannot access it). If you’ve ever seen a cut-open pipe, you’ll notice that this lower layer of water just stays inside the line, untouched.

When vaccination begins, the vaccine solution pushes out the clean water that was left in the pipes. This clean water is the first to flow into the drinker cups, not the vaccine. Even worse, it dilutes the vaccine, delays its delivery, and lowers the concentration birds receive. Birds that are far from the beginning of the drinking line may receive more of the leftover, unavailable water. As a result, they might not get the correct or full dose of the vaccine. In broiler or breeder sheds with just 2–5 drinking lines, the impact might seem small. But in commercial cage systems with dozens or hundreds of lines, this effect multiplies, causing uneven vaccine distribution, reduced efficacy, and serious gaps in flock immunity.

Why is it critical to calculate the total volume of unused (unavailable) water in the shed?

Understanding how much unused (unavailable) water is sitting in the drinking lines is essential for accurate and effective vaccination. When we begin vaccination, the solution with vaccine and dye flows into the system. But before it reaches the birds, it first pushes out the unused (unavailable) water (the clean water sitting under each nipple that birds cannot drink). This means part of the vaccine solution will simply fill those gaps, staying below nipple level and never reaching the birds. As a result, birds will not receive the full planned volume of vaccine because some of the solution is trapped in parts of the system they cannot access. This leads to under-dosing, reducing the effectiveness of the vaccination and leaving parts of the flock unprotected.

That’s why we must measure or estimate the total volume of unused water in the entire shed and add this amount to the calculated number of doses. Only then can we ensure that every bird receives the correct dose of vaccine, and that no part of the flock is left vulnerable.

-

How to calculate unused water in drinking lines and adjust vaccine doses accordingly

So, how much water is stuck under each nipple? We often don’t know exactly, but we must find out. Why?

Because this undrunk (unavailable) water fills part of the system before the vaccine reaches the birds. It is replaced with vaccine solution, but the birds can’t access it; meaning that portion of vaccine is lost. In cage systems, this can result in serious underdosing across the flock.

Conclusion

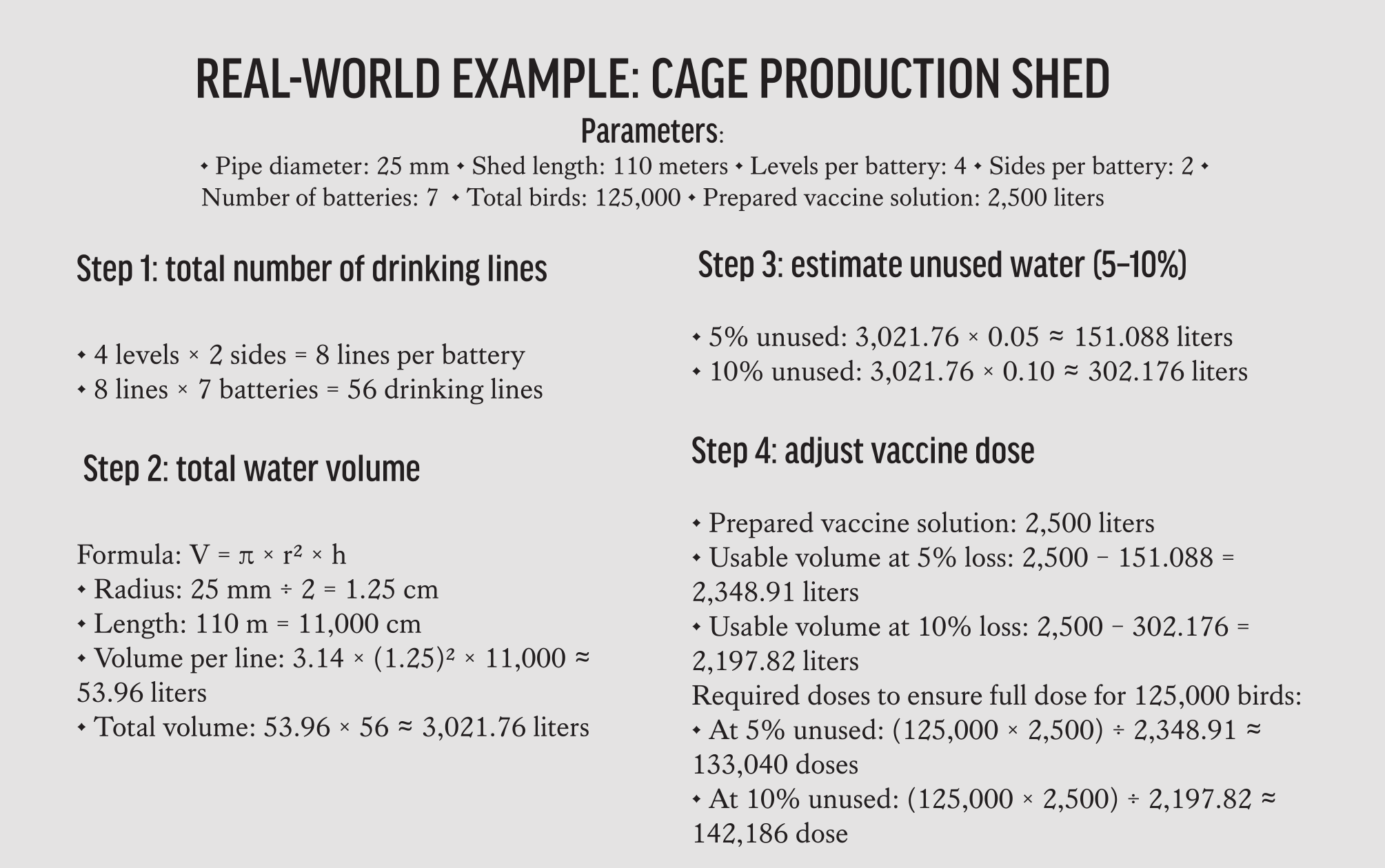

To properly vaccinate 125,000 birds in this cage system using 2,500 liters of solution:

- if 5% of water is unused, prepare 133,040 doses;

- if 10% is unused, prepare 142,186 doses.

This ensures the vaccine lost in the pipe is compensated, and every bird receives a full, protective dose.

New chapter: manual control and measuring unused water

In some cases, it’s possible and highly recommended to manually control and measure the amount of clean, unused water that is pushed out from the drinking lines during vaccination.

This approach is simple, practical, and especially useful for farm managers and technicians who want to understand how much water is sitting below nipple level, know how much of the vaccine solution will be wasted, and adjust the total number of doses more accurately.

How to do it:

- prepare the vaccination system as usual, but do not let birds drink yet;

- keep the lights off to reduce bird activity;

- go to the end of each drinking line and collect the water that flows out before the first appearance of colored (dyed) vaccine solution;

- measure this collected volume using a bucket, measuring jug, or flow meter;

- repeat this process on multiple lines to get an average (or do it on all lines if possible);

- multiply the average by the total number of lines to calculate the total unused water volume in the shed.

This value allows you to precisely adjust the total number of vaccine doses needed and to reduce underdosing risks, and ensure that vaccine coverage is consistent across the flock. Manual measurement is especially helpful when working with:

- new or unfamiliar water systems;

- different pipe sizes or slopes;

- older sheds with uneven pressure distribution;

- or when using multiple vaccine batches in sequence.