In the last ten years, the poultry industry in the USA has been hit by four devastating outbreaks of avian influenza. This article focuses on the most recent epidemic during the winter of 2024/2025, highlighting the high regional concentration of outbreaks and the resulting economic and production losses.

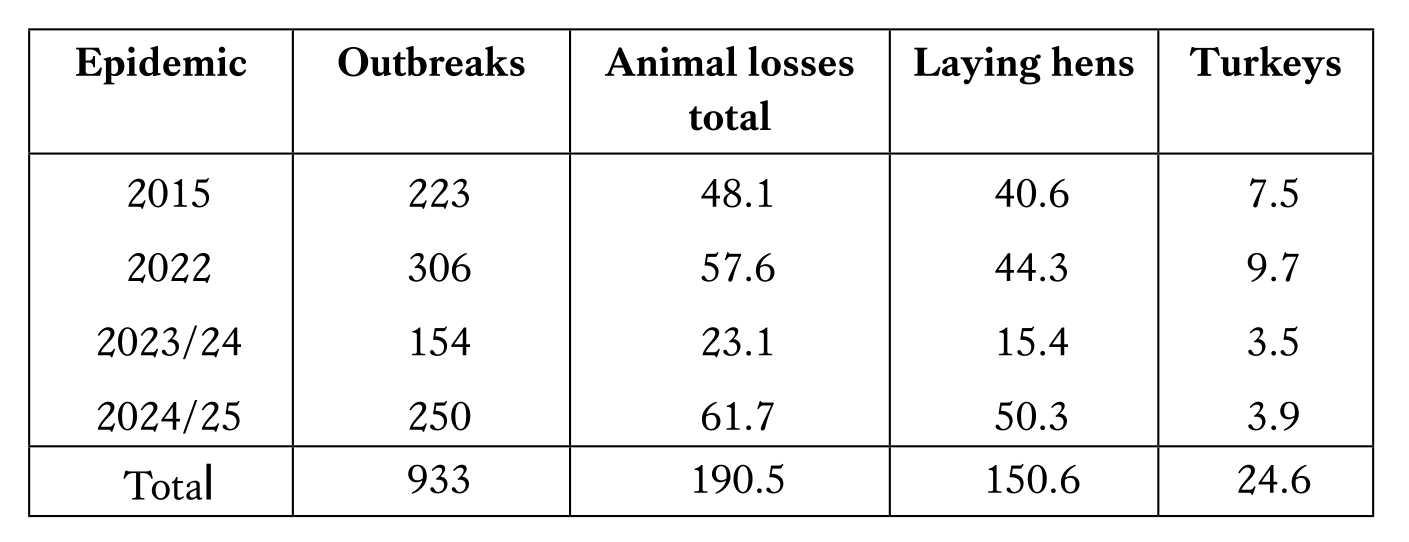

Between April 2015 and April 2025, the highly pathogenic AI virus (HPAI) was diagnosed on 933 farms. A total of 190.5 million poultry died due to virus infections or preventive culling. Of these, 150.6 million were laying hens and 24.6 million turkeys (Table 1).

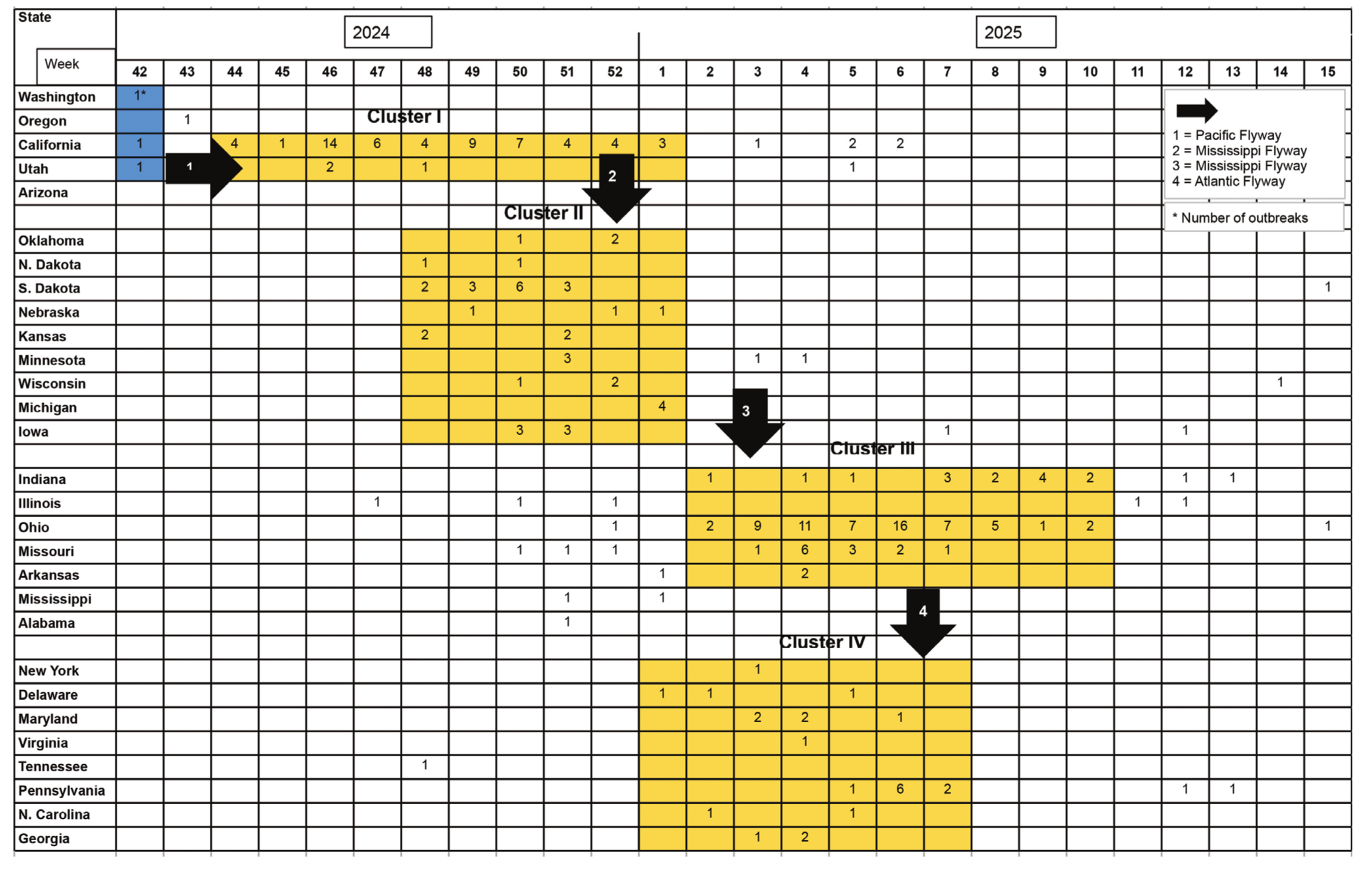

While there were around seven years between the first two epidemics, the third and fourth followed less than one year apart. After the devastating economic consequences of 2022, it was hoped that a comparable epidemic would not be repeated so soon, but the new wave of outbreaks hit the poultry industry again in the winter months of 2023/24 shortly after the recovery from the Covid-19 epidemic. After a few months in the summer without AI cases, new outbreaks occurred in the Pacific states in October 2024, and from the end of November in the western Great Plains and the northern Midwest. Shortly after the turn to the year 2025, a new cluster formed with very high outbreak cases from the central Midwest to the South-Central states and another on the eastern side of the USA from New England to the South-East. It was not until mid-March 2025 that the number of infections fell significantly.

The high animal losses in laying hens, which had a significant impact on the population’s egg supply and on egg prices, revived some issues that had already been the subject of very controversial discussions in 2022. One issue was the possibility of preventive vaccination and the other was how farms should be compensated from US Department of Agriculture (USDA) funds for animal losses due to infection or preventive culling. The pressure on the federal government to take action in these areas grew and led to reactions, which will be discussed in more detail towards the end of this article. Firstly, an overview of the course of the epidemic in 2024/25 will be given.

A remarkable timeline

Between October 15th, 2024 and April 14th, 2025, a total of 250 outbreaks of the HPAI virus in commercial farms occurred in 29 states. This revealed a remarkable spatial pattern. As Figure 1 shows, the epidemic began in the three Pacific states and Utah. Overall, large flocks of laying hens were involved. This was followed by 4 outbreaks in broiler farms in California. Numerous farms were affected here in the following weeks, with turkeys and broilers in particular being infected. A total of 62 outbreaks were registered in California by the beginning of February 2025 (Cluster I).

From the end of November 2024, a new cluster (II) formed in the northern Midwest as far south as Oklahoma. Most cases were recorded in South Dakota. The two Dakotas and Minnesota had already suffered high losses in previous outbreaks, especially in turkey flocks. However, the total number of outbreaks in this cluster was lower than in 2022 and 2023/24.

Although some farms in the eastern Great Plains and the Midwest were also infected in the last two months of 2024, especially turkey farms and some layers and broiler flocks, a larger number of outbreaks did not occur until mid-January 2025. From then on, a new cluster (III) formed around the states of Ohio, Missouri and Indiana. From mid-March, the number of infections decreased significantly, but on April 14th, 2025 a large laying hen farm in Ohio was affected. It is worth noting that California (62) and Ohio (61) not only recorded an almost identical number of cases, but also roughly the same number of animal losses (Table 2). Almost parallel to the Midwest, a fourth cluster (IV), although less massive, developed on the east side of the USA between New York and Georgia, here, mainly broiler and duck farms were affected, as well as some turkey and layer farms.

Looking at the overall spatial pattern of the outbreaks, it is obvious that it reflects the three predominant flyways of wild birds. Infections started in the West (Pacific Flyway), followed by the western Great Plains states and the northern Midwest, then the central Midwest to the South-Central (Mississippi Flyway). The Atlantic coastal states were less affected overall (Atlantic Flyway). Here, mainly broiler farms were infected, which is not surprising given the geographical pattern of broiler production in the USA.

High regional concentration of outbreaks and losses

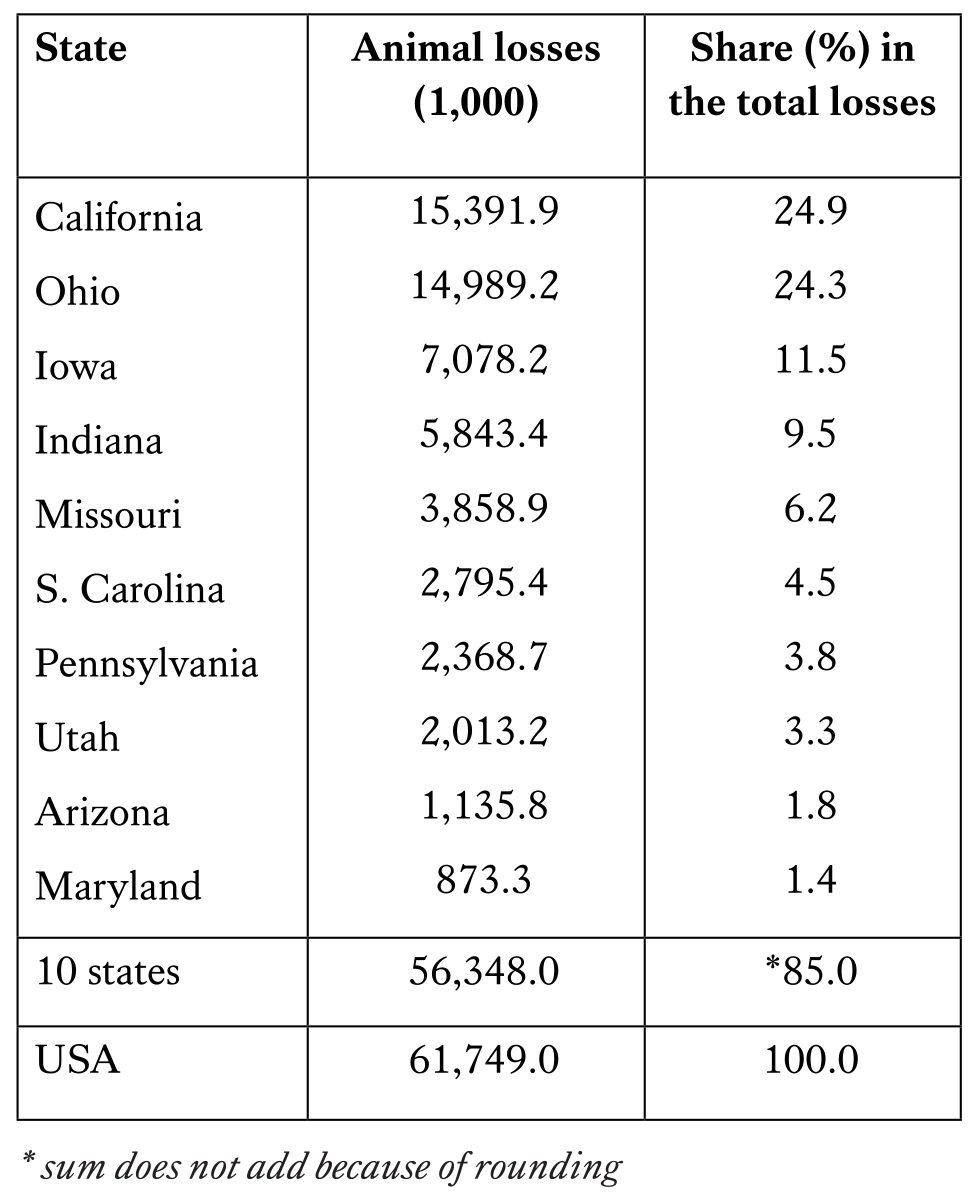

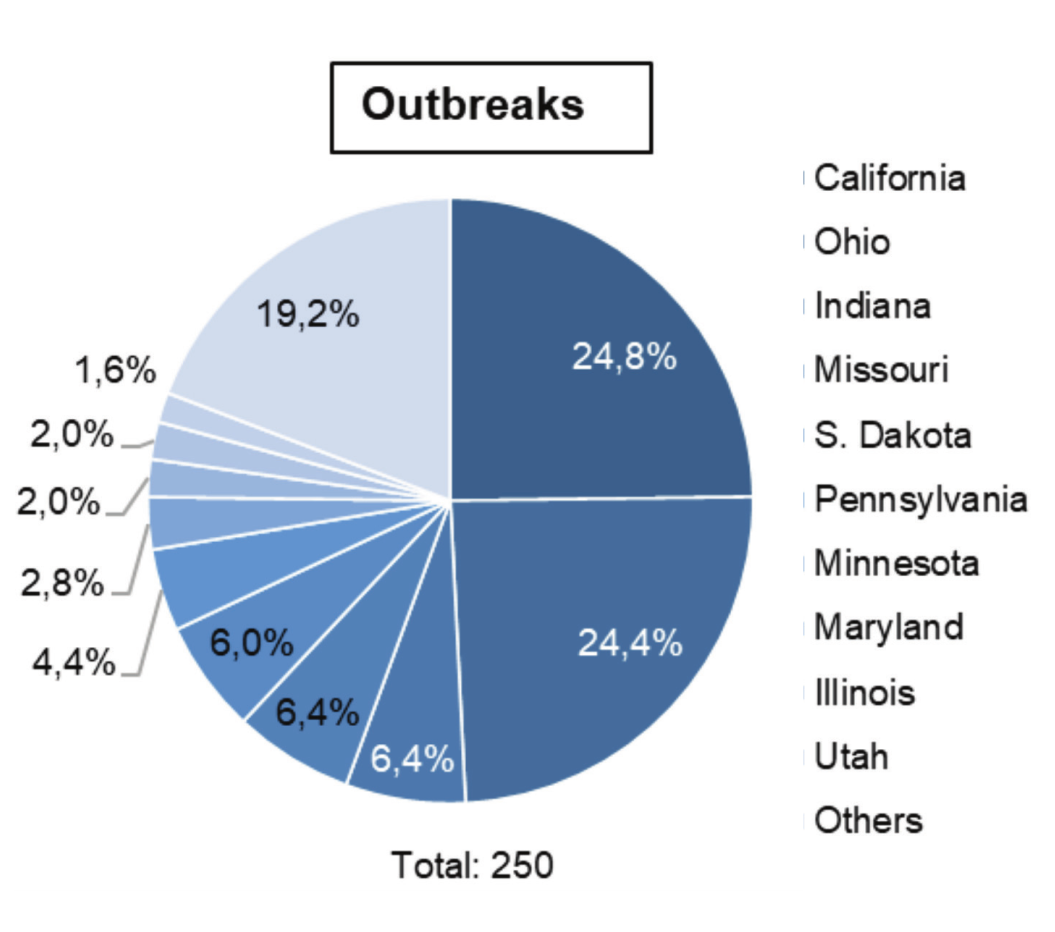

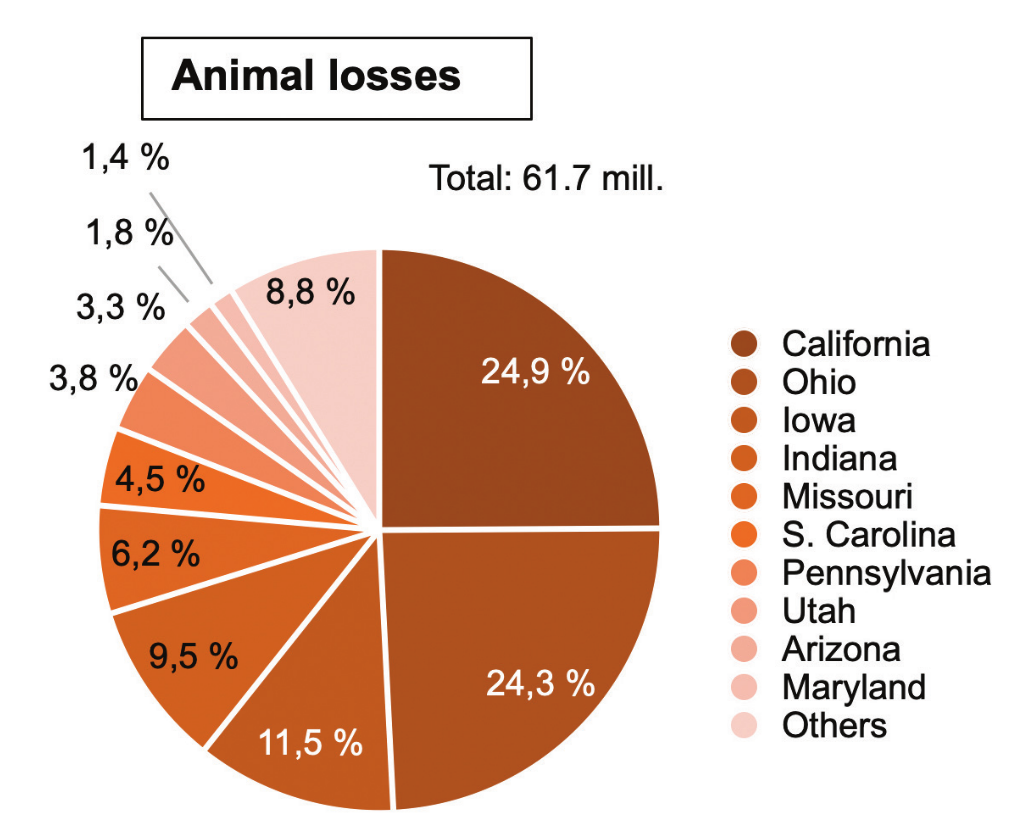

Figures 2 and 3 show the ten states with the highest number of infected farms and animal losses. Figure 2 reveals that out of a total of 250 registered HPAI virus infections in commercial poultry flocks (excluding small flocks), California and Ohio alone accounted for 123 respectively 49.2%. The regional concentration of losses was similar. Again, California and Ohio accounted for 49.2% (Figure 3). The shares of the two states during the winter 2023/24 epidemic were similar at 49.0% (Windhorst 2024). The epidemic in 2022 differed significantly from the following two, as the northern Midwest was mainly affected and the regional concentration was significantly lower (Windhorst 2023).

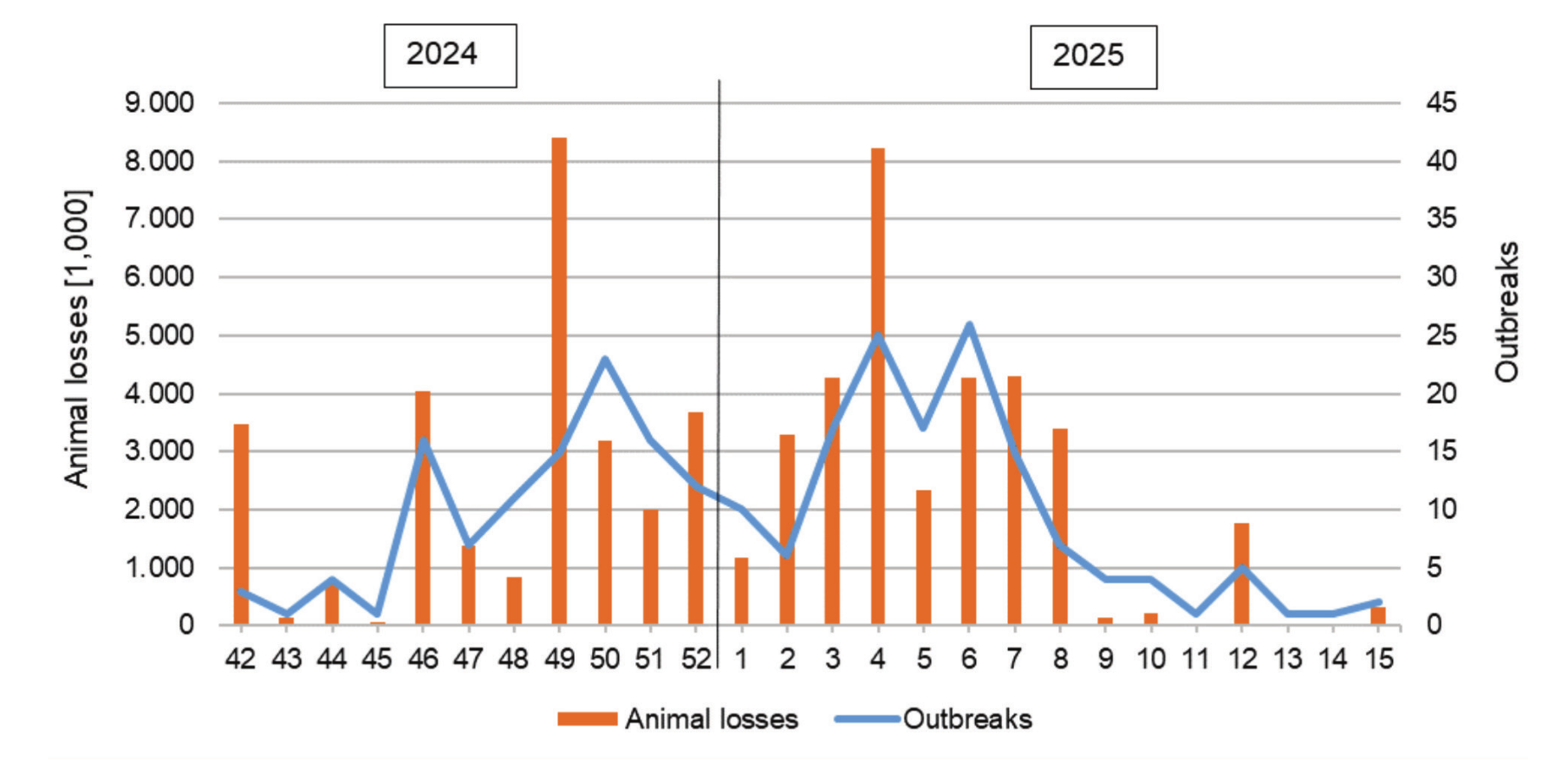

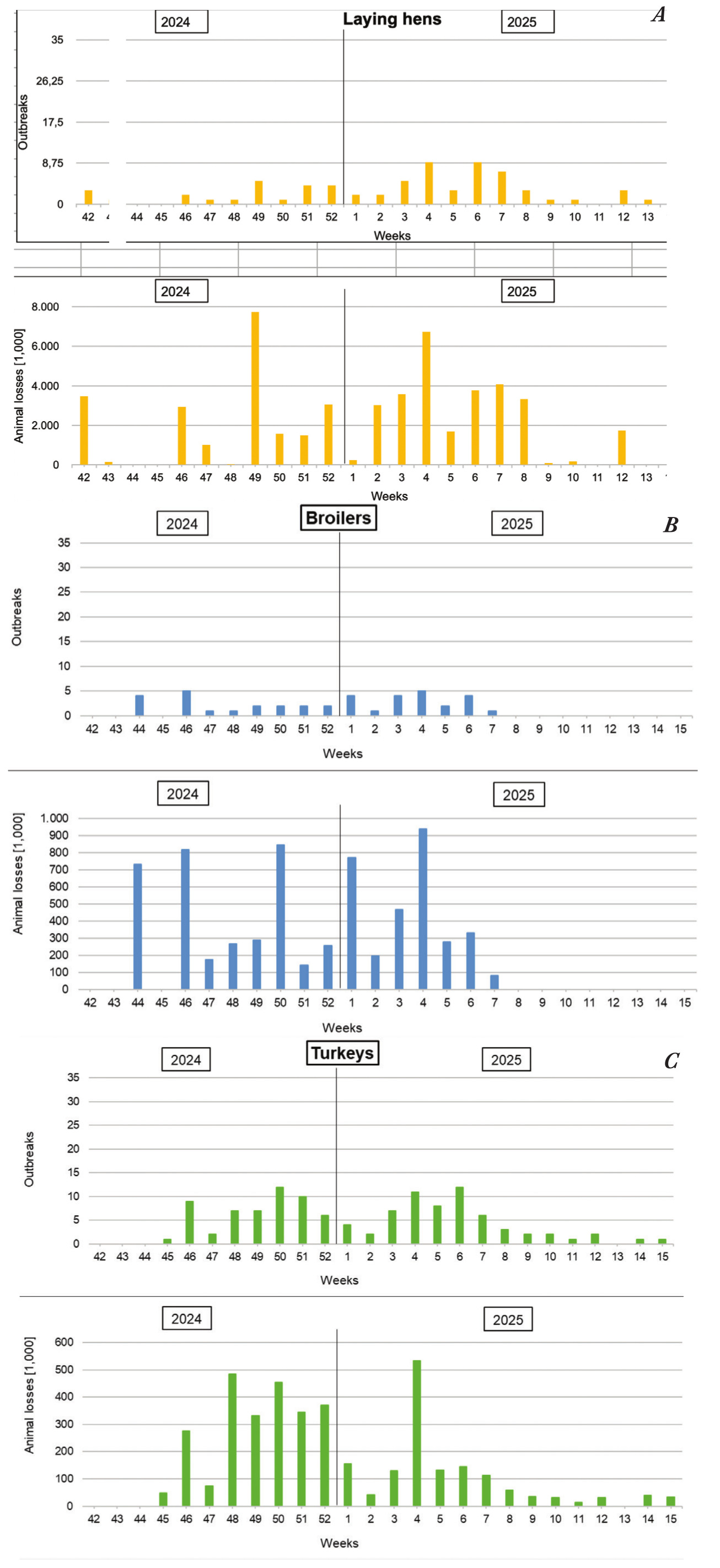

Figure 4 shows that the number of outbreaks and the associated animal losses varied considerably over time. More than 20 infected farms were recorded in three weeks, while fewer than five were recorded in nine weeks.

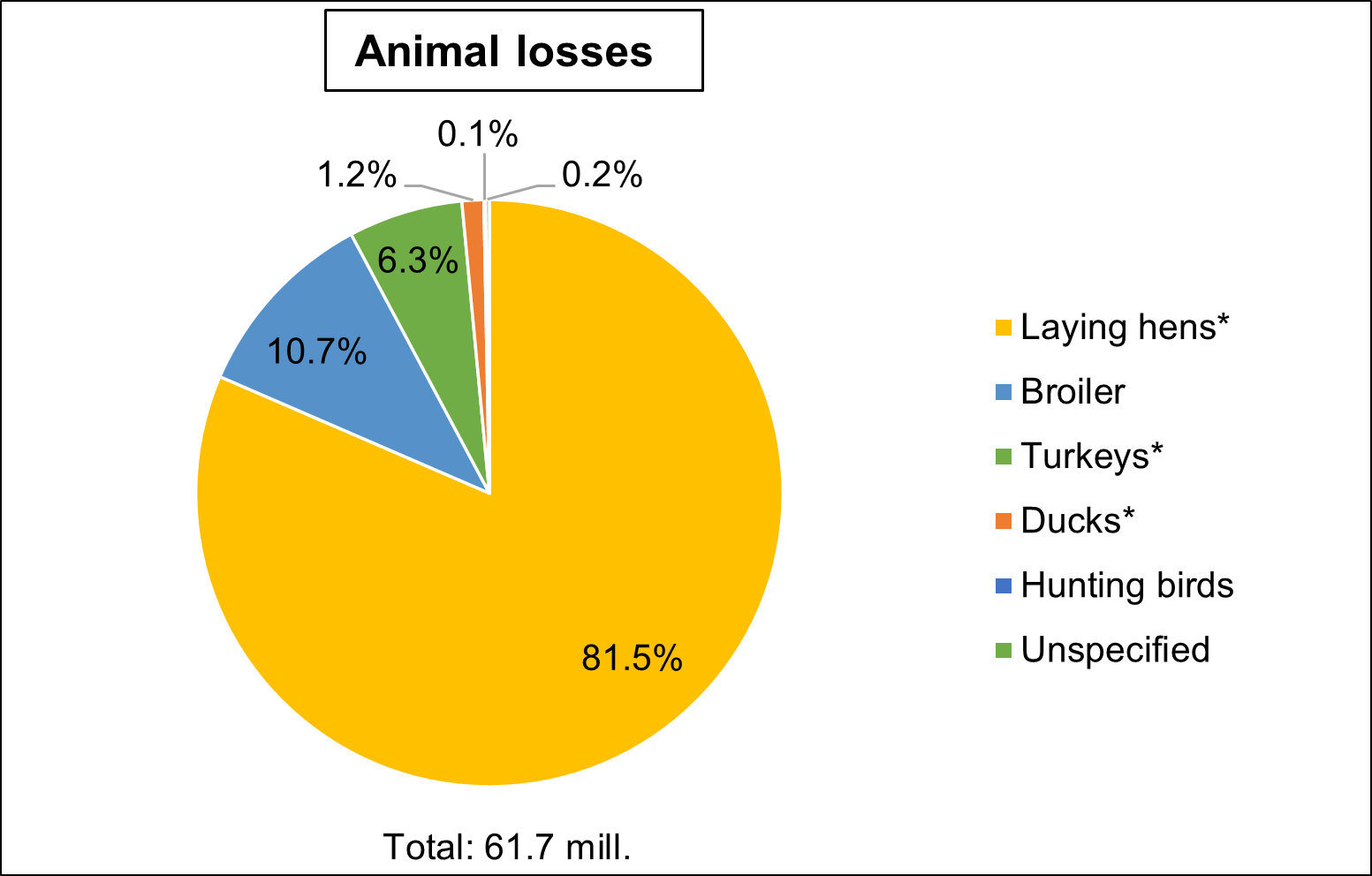

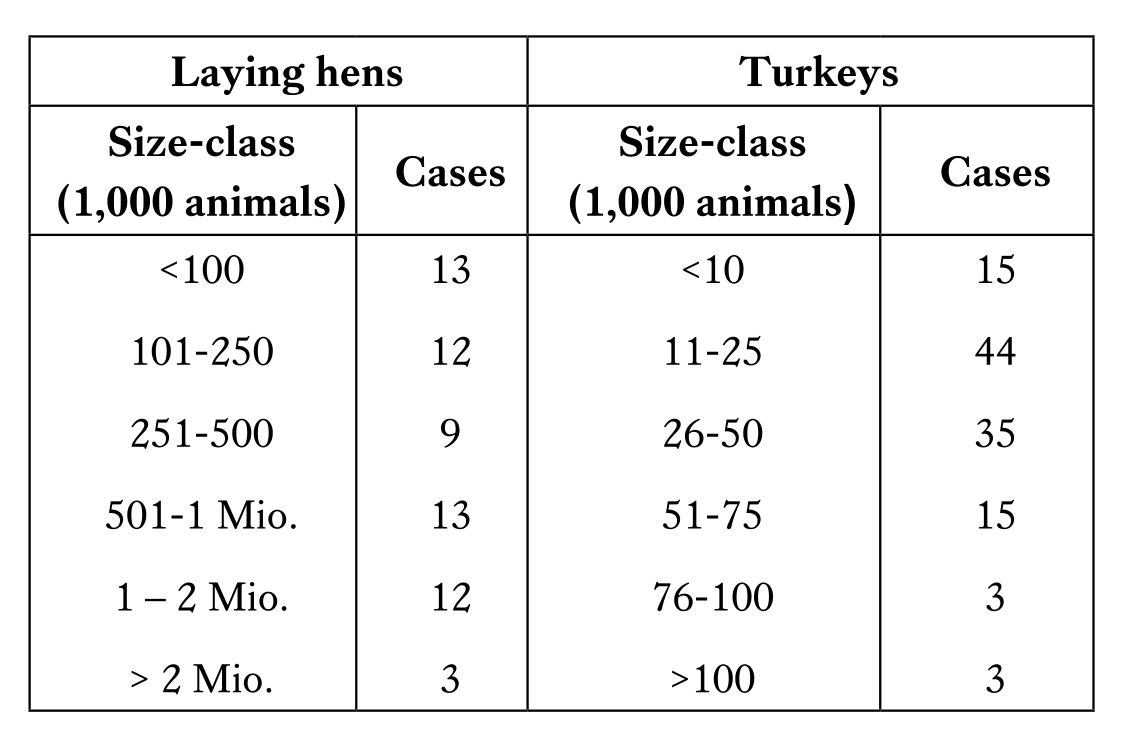

Weekly losses ranged from 15,000 to 8.4 million animals. In 16 weeks, more than 1 million animals fell victim to the virus or were culled as a preventive measure. On average, this was 2.5 million per week, causing major problems with the removal and disposal of the dead animals in the counties where laying hen farms with several million birds were affected. Comparing the graph of outbreaks and the columns of animal losses, a certain correlation between the number of infected farms and animal losses can be seen. However, this is not a direct correlation as even a low number of outbreaks led to high losses when large laying hen farms were affected, as in weeks 42/2024 and 49/2024. The number of outbreaks of the HPAI virus in the epidemic analysed here, was 96 cases or 62.3% higher than in 2023/24, and the losses of 61.7 million birds were even 38.6 million or 167.1% higher. This is mainly due to the large laying hen farms affected, with up to 4 million birds. Laying hen farms accounted for only 27.2% of the total outbreaks but 81.5% of the losses, while turkey farms accounted for 45.5% of the outbreaks but only 6.3% of the total losses. Broiler farms shared 16% in the outbreaks and 10.7% in the animals that died or were culled (Figure 5). These differences are reflected in the average size of the farms. Whereas laying hen farms had an average size of 806,000 places and broiler farms of 165,000, it was only 34,000 for turkeys. The distribution of cases by farm size class is shown in Table 3. The high economic losses that have occurred in farm complexes with several million laying hens on one site have led to a renewed discussion of whether these efficiency-oriented scales represent an undesirable development and whether housing facilities of this size should no longer be built1.

The problem of high economic losses when very large flocks are infected can be documented by comparing the number of cases with the number of animals lost per week. These are compared in Figures 6a-c for laying hens, broilers and turkeys.

Figure 6a shows that the peaks for laying hens were recorded in weeks 42 and 49 in the last quarter of 2024 and in weeks 4 and 7 in the first two months of 2025. In both cases, farms with more than 1 million places were affected, in week 42 a farm with 1.8 million hens in Utah, in week 49 a farm with 1.7 million in California and a farm with more than 4 million hens in Iowa. In week 4, there were 4 facilities with 1.2 million to 1.8 million places each in Missouri and Ohio, and in week 7, 3 facilities in Indiana with over 1 million birds each.

The highest losses in broilers also occurred in very large flocks (Figure 6b). In week 44, three farms in California with more than 100,000 broilers each were infected, and in week 46, three farms with more than 200,000 birds each. In week 4/2025, it was again a large farm in California with 441,000 broilers. Apparently, the farms were not able to protect their flocks with a high level of biosecurity.

One explanation for this could be the low number of cases on broiler farms in previous epidemics, which may have led to the assumption that broiler flocks are less susceptible to infection. Despite the smaller average size of turkey flocks (Table 3), the two peaks at weeks 48/2024 and 4/2025 were mainly due to two outbreaks in large flocks of 223,000 and 300,000 birds in Minnesota (Figure 6c).

The highest ever losses of laying hens during an outbreak and the resulting problems in supplying eggs to the population to a reasonable price, led to public protests and forced government action.

Legislative and industry response

In December 2024, APHIS published an update of the indemnity program for HPAI on poultry farms that ties future compensation to certain conditions. For example, it requires that an affected premise can only be re-populated after it has passed an APHIS biosecurity audit. It also requires an audit of commercial poultry farms within a 7 km radius of an affected farm prior to movement of poultry onto a premise if the owner wishes to be eligible for future indemnity. In addition, no compensation will be paid if animals are moved onto a premise in an active restriction zone and an infection occurs within 14 days after the restriction zone is lifted. If a farm does not implement the biosecurity improvements proposed by APHIS, it will lose its right to compensation in the event of an avian influenza outbreak. The new legislation is intended to improve biosecurity on poultry farms2. On February 18th, 2025, a group of 16 senators from both parties wrote a letter to the Secretary of Agriculture calling for the development of a forward-looking strategy regarding the development of vaccines and their use in laying hen and turkey farming, as well as the conduct of field trials with such vaccines. In addition, negotiations should be initiated with trading partners to convince them of the need to vaccinate poultry flocks and that a vaccination should not hinder or prevent the trade of poultry products3.

In April 2025, the USDA committed $100 million to enable scientists to develop new vaccines to protect poultry flocks and to study the spread of the AI virus in wild birds and in livestock. This should, if not prevent a recurrence of an epidemic, at least reduce its size4.

Data source and cited literature

APHIS: Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in commercial and backyard flocks. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/commercial-backyard-flocks

APHIS: APHIS Announces Updates to Indemnity Program for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza on Poultry Farms. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/agency-announcements/aphis-announces-updates-indemnity-program-highly-pathogenic-avian

Windhorst, H.-W.: Economic impacts of the AI-outbreaks in the USA in 2015. A final evaluation of the epizootic disaster. In: Zootecnica International 38 (2016), no. 7, p. 34-39.

Windhorst, H.-W.: A documentation and analysis of the AI epidemic in the USA in 2022. In: Zootecnica International 45 (2023), no. 3, p. 8-17.

Windhorst, H.-W.: Third Avian Influenza outbreak in the USA within 10 years: the 2023-2024 epidemic. In: Zootecnica International 46 (2024), no. 9, p. 28-33.

Notes

1 Doughman, E.: Stopping HPAI may require changes to poultry farming. https://www.wattagnet.com/poultry-meat/diseases-health/avian-influenza/news/15743723/rethinking-poultry-farms-to-combat-avian-flu

3 https://www.ernst.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/letter_to_usda_in_response_to_hpai_outbreaks.pdf

4 https://www.aphis.usda.gov/funding/hpai-poultry-innovation-grand-challenge