How to effectively manage and reinforce best practice in biosecurity on broiler farms

This article examines best practice in broiler production, focusing specifically on biosecurity. How do farms promote robust biosecurity when sites can vary so much in size, operational capacity, and budgetary allowance?

Biosecurity is widely understood as a critical part of effective poultry production within the industry, with effective management preventing the spread of external disease which, if not stopped, can severely impact a farm’s bottom line. This is summed up well by Daniel Dring, Poultry Welfare Officer at PD Hook Group, who urged poultry farmers to take biosecurity seriously at the 2015 UK Poultry Health and Welfare Group (PHWG) AI roadshow in Perth, Scotland: “You shouldn’t underestimate the cost of an outbreak. It can be anywhere from £500,000 to £10m. You, as the producer, pick up the cost for secondary cleansing and disinfection and face not being able to operate for a significant period of time.”

Biosecurity is a broad term, so much so that it risks being unspecific. What does it mean for the individual grower? According to Neal Samet, Product Manager at Livetec Systems, it’s essential that poultry farms take the time to occasionally refresh themselves on its basic principles. “Too often we have seen the devastating impact of disease on farms,” says Neal. “We have to make sure strong biosecurity runs through the farm at all levels, not just in the sheds, to avoid the tragedy of an outbreak. Taking the time to review your farm setup goes a long way towards doing so.”

Critical points

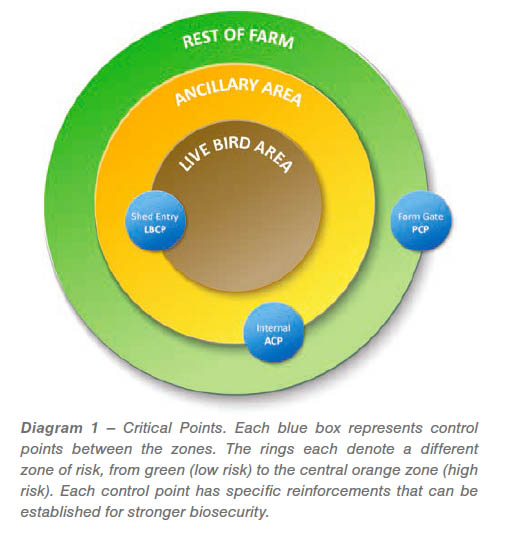

Detailed plans for biosecurity are created based around critical control points. All farms have these principle zones that are designed to control movement, and allow for the enforcement of strong biosecurity measures. The division of these can be seen in the Diagram 1.

Each blue box represents control points between the zones. The rings each denote a different zone of risk, from green (low risk) to the central orange zone (high risk). Each control point has specific reinforcements that can be established for stronger biosecurity.

Farm Gate Perimeter Control Point (PCP)

As the main access to the farm, this is ground zero for most threats. However, each farm’s layout is different, making it unlikely that the PCP can act as the first biosecurity control point. Regardless, some universal measures can establish best practice for biosecurity, even at this point. All visitor and staff cars should be parked in this first area, and signs placed instructing delivery drivers, or visitors to the Poultry Unit, who they should contact, where they should sign in and where the biosecurity control point is located. If there is more than one entrance, these should be locked and not permit any visitors.

Internal Ancillary Area Biosecurity Control Point (ACP)

This should be the singular point of access to the Poultry Unit on the farm. Only essential vehicles (such as feed wagons) and personnel should be allowed in the area. There should be separate pedestrian and vehicle control points, where entrants change into site boots, sign in and, if possible, shower. Vehicle entry should be via concrete with a wash-water collection system. A clean and dry place should be provided for changing boots and overalls, in addition to washing and disinfecting equipment and vehicles.

Shed Entry Live Bird Control Point (LBCP)

The floor surface must be kept clean at all times, with no rubbish or clutter. Regular cleaning must be performed on both sides of the barrier. All visitors should wear overalls over their outside clothing and, if possible, wear hair nets and wash their hands using provided facilities. A barrier system of at least 30 cm with a seat should be provided for changing from site boots to shed boots. Site boots should never touch the shed side floor nor should shed boots ever touch the site side floor.

The above diagram breaks down the farm into manageable areas, allowing us to better understand how a possible disease could pass through a farm, and how best to prevent it.

“Starting from PCP through to the Live Bird Area, which points along the way will your biosecurity measures halt a disease in its tracks?” asks Neal. “Where are your weak points? Consider your biosecurity from the outside in. Imagine a delivery driver comes to the farm who is unknowingly contaminated. From PCP through to the Live Bird Area, mark areas of improvement and implement changes. The investments are worth it – weak biosecurity ultimately costs the farm much more.”

Managing risk effectively

The work does not stop at control points. As Dr Hosam Amro, Senior Manager Technical Service at Cobb Europe, puts it: “Farm sanitation is key to establishing and maintaining a healthy breeder flock. The first step is a multifaceted cleaning plan which includes a rigid set of principles, good husbandry and management practices as well as a clear employee understanding of the importance of the cleaning process.”

Poultry farms must adopt a holistic and proactive approach to biosecurity that encompasses every level of their farm, from employee behaviour through to surroundings and contingency planning.

“Every poultry farm has levels of risk to manage,” says Neal. “Having visibility and knowledge into your operations – and those areas in which you’re likely to be vulnerable – is key. For example, best practice would include establishing a 3 kilometre radius away from risks like other poultry units, pig units, public rights of way, and bodies of water or wetlands that could attract wild birds. Without proper oversight, these areas can go unnoticed and weaken an otherwise secure biosecurity programme.”

This diligence should extend to employees too. All employees should avoid potential contaminants. This includes poultry at home (parrots fall under this classification), visits to parks, zoos and pet stores and taking part in game shoots. Biosecurity must always come first and form an ingrained part of your business’ working culture.

At every possible occasion, farms should be made unattractive to rodents and pests. This means keeping areas tidy, cleaning up any feed spills, controlling weeds, and never leaving old machinery or rubbish lying around the site.

Similarly, cleansing and disinfection is important practice for robust biosecurity. “Under practical farming conditions site sterilization is impossible,” says Dr Amro. “However, every measure which helps reduce the risk of infection is worthwhile. Sound biosecurity makes it more likely to obtain successful breeder production results.”

Technological advances have made strengthening overall biosecurity a simpler process for poultry farms, including on site cameras, boot tagging, and remote control access. Naturally, these require financial investment, and may not be accessible to all farms. Even simple technology, like coded door locks, can go a long way to preventing unauthorized access to biosecure areas.

Planning for the future

If there is a breach in biosecurity and your farm is compromised, how do you deal with it? Poultry farms can be hit hard by disease, but it’s important not to wait until disaster strikes. Instead, be proactive and develop a contingency plan for mitigating the damage and getting your business turned around as speedily as possible.

“Every element should be planned for,” adds Neal. “Biosecurity is the strongest safeguard we have, but no farm is infallible. Taking protective measures can limit outbreaks but have a plan for what to do if an area is compromised. Plan for the worst but do all you can to ensure it never happens.”

“The smallest thing can bring disease onto a farm. Creating a robust biosecurity strategy from the outside in is essential for keeping your flock healthy and business thriving. Take a step back, review your current practices and make the necessary improvements. You are your own best line of defence when practicing strong biosecurity.”