The global supply of poultry products will need to double by 2050 if we are to meet the aspiration of all people to be food secure. We will need to produce more poultry meat in the face of changing consumer perceptions and constrained resources. Consumers expect this to be achieved in a sustainable manner. The industry has the skills to achieve this. Genotypes continue to improve; production methods and business models are evolving; and we have enhanced our knowledge of poultry health and nutrition. However, our industry will need to develop by offering alternative products and by changing or improving production methods. These changes will occur in the foreseeable future.

The overarching consideration will be sustainability. The definition of sustainability is straightforward – sustainable systems should meet the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In practice, sustainability is a concept with multiple facets, namely environmental, social and economic. Measuring sustainability is difficult because it depends on which metric is chosen for use, and often it can only be accurately determined in hindsight. Achieving alignment in one area often leads to failure in another, which is a challenge faced by broiler producers and legislators. For example, alternative production systems such as free-range and organic result in an apparent improvement in welfare, but at considerable cost to the environment.

There is a divide between global citizens. In developed countries, wealthy citizens consume poultry meat produced by ‘integrators’, delivered via well-developed supply chains, and sold through supermarkets and fast service restaurants. However, it is estimated that there are 2.5 billion people who depend on small farms for their livelihood and food security. These farmers have no access to supply chains, either for inputs or for the sale of product. Yet meat consumption is aspirational and poultry forms an important component of dietary protein supply. Most consumers desire access to cheap, safe animal protein, yet our industry is obliged to meet the changing consumer demands of more developed markets. Both market channels will need to be supplied in a sustainable way. Against this background, the primary focus of this paper is the nutritional interventions that can be applied to enable our industry to fulfil its mandate to ensure food security, sustainably.

Sustainability and demand

Sustainability is neither a single entity, nor can we choose those aspects that suit our own particular beliefs. From an environmental viewpoint, sustainability impacts the entire poultry supply chain, causing pollution and ecological degradation. Social aspects of sustainability encompass both human and animal well-being. The compact of the five freedoms of welfare should be applied to all animals, while human health – including exposure to antibiotic- resistant bacteria and the well-being of poultry producers – needs to be considered.

Paradoxically, most consumers are more concerned about their own well-being through the consumption of ‘natural’ products than about animal welfare. The final and seminal aspect of sustainability is financial viability, which is the key enabler of all production systems.

From a nutritional perspective, all the objectives of sustainability should be aligned. The more efficiently chickens utilise feed, the more viable the feeding operation becomes, with a reduced carbon footprint through a lower demand for resources. Appropriate nutrition will also impact on bird welfare. The poultry industry believes that bird welfare and food safety are better when conventional systems are used, but this is not a view shared by wealthy consumers in the developed world. Public opinion is that ‘organic’ is natural, healthy and sustainable, and that use of medication and intensive farming is bad. Many of these beliefs are based on perception and misinformation, often created by the poultry industry itself, which has used ‘Hormone free’, ‘Drug free’ and ‘Free range’ as marketing slogans for decades. The danger of consumers imbibing harmful drug residues from eating poultry products, and the possible contribution of these drugs leading to an increase in drug-resistant bacteria, are more a perception than a reality. Regardless of the truth, failure to meet consumer demands will result in their rejection of our products. This happened in Norway, for example, where it was perceived that the use of ionophores was undesirable. The reduced demand for poultry meat ultimately led to the voluntary withdrawal of ionophores from all broiler diets. Alternative production systems place a higher burden on the environment than conventional systems. Petersen (in 2017) estimates that, if only one-third of the US broiler industry were to switch to the use of slower-growing breeds, an additional three million hectares/year of land would be required to grow the necessary feed ingredients, while, “large scale antibiotic-free production will increase the industry’s carbon footprint”. More affluent people tend to eat fewer grains and more meat and high-value foods. The price of poultry substitutes, for example fish and beef, are likely to increase disproportionately, further fuelling demand for poultry. The poultry industry’s innovative approach to product development has also led to increased demand. A rising demand for poultry products with specific quality and food safety attributes is likely, probably linked to increased levels of affluence. In essence, the poultry industry will be expected to produce increased quantities of different product types, sustainably, without access to some technologies it has used for decades, and still make profits. Improved growth performance and feed efficiency will have a greater impact on sustainability than any other factor. Avendaño (in 2017) state that the feed conversion ratio of broilers is improving by two to three points per annum. By simple calculation, a two-kilogram broiler, grown a decade from now, will require about 500 g less feed than it does today. This will reduce the environmental impact and make broiler production more financially robust. In short, chicken is the most sustainable meat option available.

Improved feed utilization

The utilization of feed chemicals by the broiler relies on a complex web of ‘cross-feeding’. This involves the substrates contained in the diet, the birds’ endogenous enzymes, enzymes produced by the gut microflora, and the few exogenous enzymes added to the feed. The use of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) masks imbalances in the gut microflora to a certain extent, although we still do not fully understand their mode of action. In future, we will need to unravel the complexity of the relationship between the broiler, its GIT microflora, the diet being consumed and the additives used. Improving nutrient utilization involves far more than simply enhancing dietary digestibility and some 400 kcal/kg of energy, 70% of phosphorus and between 10 and 20% of the essential amino acids in a typical broiler diet are not utilised. Indigestible substrates offer a resource to the nutritionist. Exogenous enzymes enhance digestion of substrates but also break down some of the anti-nutritional factors that occur in typical diets, rendering them harmless. This leads to reduced inflammation and enhanced nutrient uptake. In addition, enzymes prevent the nutrients that escape digestion from becoming a source of nutriment for the GIT microflora. A broiler with a healthy, well-functioning GIT and a stable gut microflora will utilise its diet more effectively, resulting in enhanced digestibility. A well-developed gizzard leads to improved energy utilization. Undigested nutrients represent a food source for the GIT microflora and may induce a shift to more proteolytic bacteria, which can lead to enteritis.

Protein

Modern genotypes require more protein and less energy per unit of growth than their predecessors. The efficiency of utilization of protein is unlikely to change, but proportionally less protein will be used for maintenance purposes and more for protein-rich tissue production, such as breast meat. Future protein supplies will be more constrained than energy, which is likely to increase the cost of protein. However, the efficiency of broiler production will enable our industry to afford more expensive protein when compared to less efficient competitors.

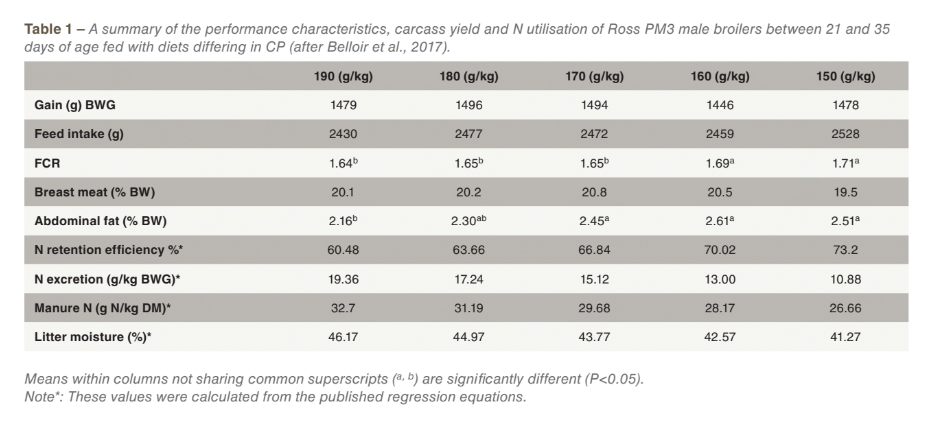

High dietary crude protein (CP) levels in broiler diets place a burden on the environment. Broilers that consume high protein diets emit more nitrogen (N) and ammonia. Ammonia is emitted from the manure through the breakdown of undigested protein and uric acid. It is responsible for water pollution (eutrophication) and soil acidification. Legislators in Europe have placed limits on the levels of nitrogen allowed in poultry manure. Precise protein nutrition is beneficial to the sustainability of broiler meat production. For example, avoid feeding ingredients that are refractory to digestion (heat damage) or retard gut health and increase disease challenge (inflation and immunity demand protein). Simply reducing dietary CP is a strategy that will have both economic and environmental outcomes. It involves the use of enzymes and crystalline amino acid, or perhaps a simple reduction in feed specifications. Alhotan and Pesti (in 2016) emphasize that it is important to meet the non-essential amino acid requirements. They demonstrate that requirements for growth and feed conversion differ, but that an ideal ratio between the amino acid level of the diet and its true protein content (TP) exists. Practically, dietary protein may be reduced to a point that impairs performance and loses opportunity. Modern broilers are highly responsive to an increased level of dietary protein in terms of body weight, FCR and breast meat yield. This effect appears to be independent of dietary energy content.

End of first part.

References are available on request

From the 2019 Proceedings of the Australian Poultry Science Symposium