A specified minimum ventilation rate based on age of flock in weeks suggests that the amount of moisture needing to be removed from a house doesn’t really change much over the course of a week. Though this may be true towards the end of the flock, it is far from the truth during brooding. The objective is to make adjustments to minimum ventilation fan settings at the first sign that house moisture levels are building, before moisture levels build to the point where the litter cakes over.

Michael Czarick, Extension Engineer

Brian Fairchild, Extension Poultry Scientist

University of Georgia, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

Why does litter seem to suddenly cake over just prior to turning the birds out into full house? In many cases it is simply because minimum ventilation fan settings are not being changed quickly enough to keep up with the rapidly increasing amount of moisture the chicks are adding to the litter. This often occurs because suggested minimum ventilation fan settings are often provided in terms of age of bird in weeks. The problem with this is that a specified minimum ventilation rate based on age of flock in weeks in a way suggests that the amount of moisture needing to be removed from a house doesn’t really change much over the course of a week. Though this may be true towards the end of the flock, where minimum ventilation rates to control moisture often change less than five percent from week to week, it is far from the truth during brooding, where due to the extremely high chick growth rates minimum ventilation rates, can increase twenty percent or more in just 24 hours.

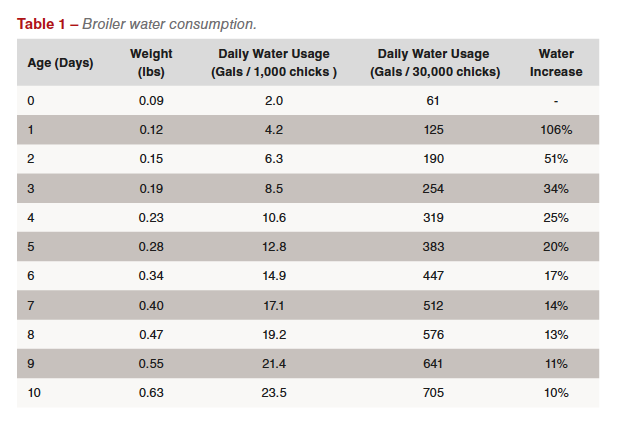

Over the first ten days of a flock, the weight of the chicks typically increase seven-fold. To obtain this tremendous weight gain, the amount of water the chicks consume increases equally dramatically. For instance, water usage increases from approximately 2 gals/1,000 chicks on the placement day to approximately 4.2 gals/1,000 chicks in just 24 hours. By Day 4, water usage increases to over 10 gals/1,000 chicks and by Day 10, 24 gals/1,000 chicks. Roughly a ten-fold increase in water consumption in just ten days (Table 1).

It stands to reason that as water intake increases dramatically, the amount of moisture the birds are adding to the air and litter in a house will increase in a similar dramatic fashion. Since our goal is to maintain a relatively constant, low litter moisture, minimum ventilation rates need to increase roughly proportionally the amount of water the chicks are consuming each day. For instance, if the birds drink 200 gallons in a day, roughly 200 gallons of water need to be removed from the house through ventilation to maintain a constant level of litter moisture.

Though it is true that the chicks will retain roughly 20% of the water consumed to build meat, tissues, blood, etc., they are also “building” a significant number of water molecules as they chemically break down the feed in their digestive tracks. So the chicks are not only drinking water, they are also creating water from the feed. In fact, the chicks are actually producing an amount of water from the feed roughly equal to that which is being retained in the form of body tissues, etc. The net result is that for every gallon of water the chicks consume, roughly a gallon of water is added to the air and litter in the house which needs to be removed through ventilation.

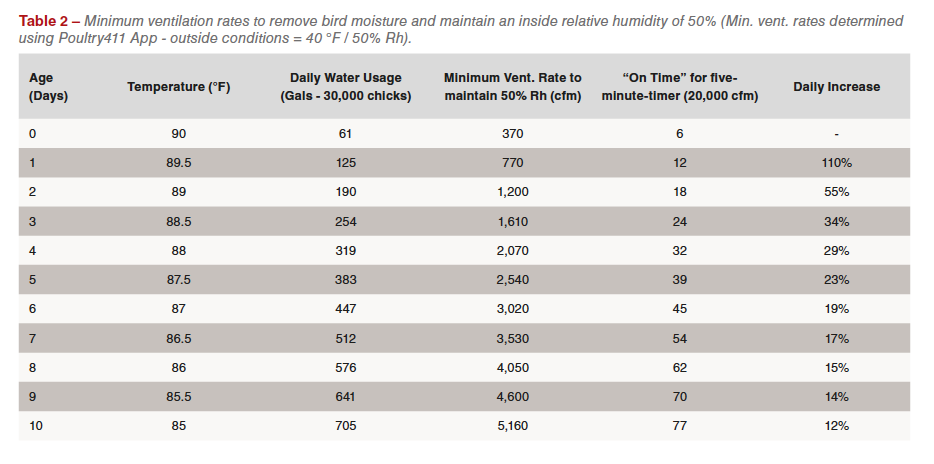

Table 2 provides an example of the calculated daily minimum ventilation rates required to remove the moisture that 30,000 chicks are adding to a house over the first ten days of a flock. The values in the table were calculated assuming an outside temperature of 40oF and a relative humidity of 50%. The inside relative humidity was set at 50%. The calculated minimum ventilation rates to control moisture shown for the first few days of the flock are much lower than would typically be utilized in most poultry houses. This is because the minimum ventilation rates illustrated in Table 2 are only sufficient to remove moisture added to a house by the birds and not the additional moisture which may be added by a house’s heating system. For each gallon of propane, nearly one gallon of water is added to the air in a house. So if on Day 1, 100 gallons of propane are burned to maintain the proper house temperature the moisture added to the house by combustion of 100 gallons of propane could be equal to that added by the 30,000 birds thereby requiring a doubling of minimum ventilation rates shown in Table 2.

Table 2 provides an example of the calculated daily minimum ventilation rates required to remove the moisture that 30,000 chicks are adding to a house over the first ten days of a flock. The values in the table were calculated assuming an outside temperature of 40oF and a relative humidity of 50%. The inside relative humidity was set at 50%. The calculated minimum ventilation rates to control moisture shown for the first few days of the flock are much lower than would typically be utilized in most poultry houses. This is because the minimum ventilation rates illustrated in Table 2 are only sufficient to remove moisture added to a house by the birds and not the additional moisture which may be added by a house’s heating system. For each gallon of propane, nearly one gallon of water is added to the air in a house. So if on Day 1, 100 gallons of propane are burned to maintain the proper house temperature the moisture added to the house by combustion of 100 gallons of propane could be equal to that added by the 30,000 birds thereby requiring a doubling of minimum ventilation rates shown in Table 2.

Another important assumption used in creating Table 2 is that ALL the fresh air brought into a house is entering through air inlets and is properly heated and dried before moving down to floor level. Cold air entering through cracks, loose-fitting doors, fan shutters, curtains, etc., can quickly fall to the floor and since its moisture-holding ability is lower than warmed air which entered through the air inlets, it is less effective in removing moisture from the litter. As a result, the looser the house, the more the minimum ventilation rates show in Table 2 would need to be increased to compensate for the fact that the air moving over the litter is cooler and wetter than if it would have been had it entered through the house’s side wall inlets. Last but not least, the minimum ventilation rates provided in Table 2 assume that there is little to no ammonia present and that carbon dioxide concentrations are at an acceptable level.

So though the minimum ventilation rates shown in Table 2 may not be precisely what is required to maintain proper air quality over the first ten days of a flock, Table 2 does make clear how quickly minimum ventilation fan settings may need to be increased to keep litter moisture levels from getting out of control. On average, minimum ventilation rates to control bird moisture increase approximately 30% per day during the first 10 days of a flock. If minimum ventilation rates are not adjusted on a nearly daily basis, dry litter can turn to caked litter in just a matter of days.

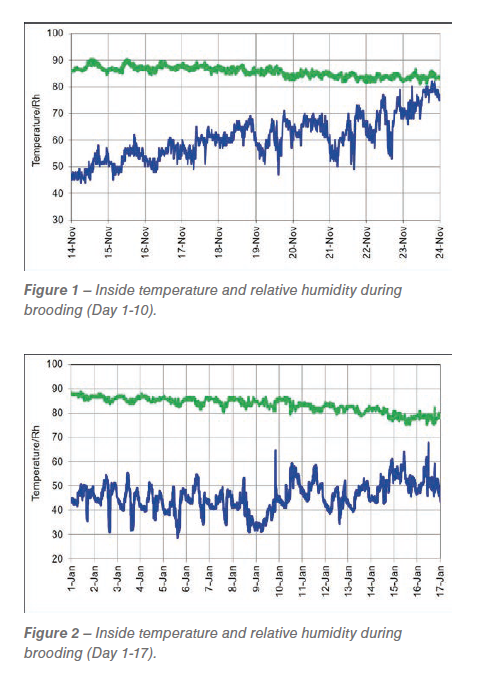

The best way to determine you are falling behind when it comes to getting rid of excess moisture is to track the relative humidity of the air in a house on a daily basis. It if is increasing, the birds are adding more moisture than the minimum ventilation fans are removing (Figure 1). If it is decreasing the minimum ventilation fans are removing more moisture than the birds are adding. If the relative humidity is staying roughly the same from day to day, the minimum ventilation fans are essentially removing all the moisture the birds are adding to the house and litter moisture levels will remain essentially constant (Figure 2).

The objective is to make adjustments to minimum ventilation fan settings at the first sign that house moisture levels are building (increasing Rh), before moisture levels build to the point where the litter cakes over, ammonia levels rise, and bird health starts to suffer. Be proactive, not reactive. If the relative humidity is increasing during brooding it is crucial that relatively large changes in minimum ventilation rates are made to bring house moisture levels quickly back in check. Increasing minimum fan settings a few percent will accomplish very little. First, if relative humidity levels are trending upward for a number of days, this means a significant amount of moisture has been added to the litter, which will need to be removed to bring litter moisture levels back down where they are supposed to be. Secondly, less than a 50% increase in minimum ventilation rates will not likely have a significant impact on house moisture levels due to the fact that around a 20% increase in minimum ventilation rate would be required just to keep up with the daily increase in the amount of moisture being added to a house by the birds. The quicker the response, and the more dramatic the change made to minimum ventilation fan settings, the more likely litter caking and all the problems associated with it will be avoided.

The objective is to make adjustments to minimum ventilation fan settings at the first sign that house moisture levels are building (increasing Rh), before moisture levels build to the point where the litter cakes over, ammonia levels rise, and bird health starts to suffer. Be proactive, not reactive. If the relative humidity is increasing during brooding it is crucial that relatively large changes in minimum ventilation rates are made to bring house moisture levels quickly back in check. Increasing minimum fan settings a few percent will accomplish very little. First, if relative humidity levels are trending upward for a number of days, this means a significant amount of moisture has been added to the litter, which will need to be removed to bring litter moisture levels back down where they are supposed to be. Secondly, less than a 50% increase in minimum ventilation rates will not likely have a significant impact on house moisture levels due to the fact that around a 20% increase in minimum ventilation rate would be required just to keep up with the daily increase in the amount of moisture being added to a house by the birds. The quicker the response, and the more dramatic the change made to minimum ventilation fan settings, the more likely litter caking and all the problems associated with it will be avoided.