Biosecurity is today a primary factor in farming. The poultry world has entered a new era driven by increasingly demanding consumer and regulatory expectations. These expectations have created new market opportunities and challenges that compel producers to evolve to remain competitive and sustainable. During recent years one of the challenges has been the number of outbreaks of highly pathogenic Influenza (HPAI), which have caused great economic losses due to mortality, reduced performance, costs associated with eradication/control procedures, and long-term disruptions in trade. According to a report from Rabobank (RaboResearch/Poultry Quarterly Q1 2018/December 2017) the outlook for the global poultry industry is promising; however one of the main concerns is continuing volatility caused by Avian Influenza (AI). This report concurs with industry publications declaring that AI has become a new reality driving changes in business and control strategies.

Growing consumer demand and resulting shortages of poultry meat and eggs will continue to benefit leading operations with high biosecurity standards, as well as bolster the imports from producers in regions or countries free from AI. Furthermore, this emphasizes the need for the acceptance and adoption of the principles in the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) code for safe trade in poultry and poultry products, such as regionalization and compartmentalization, and the implementation of science-based surveillance programs. Development and recognition of primary breeder compartments in particular (established on the basis of stringent biosecurity and surveillance programs) will also help to ensure the supply of critical genetic stocks for producers around the world.

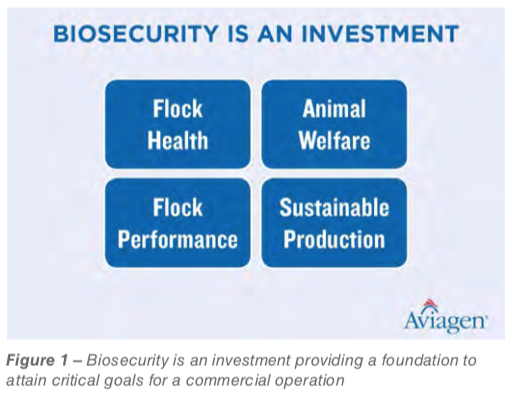

Biosecurity is defined as a comprehensive set of policies and practices to prevent the introduction and spread of disease causing organisms. It serves as the first and main barrier of protection against all diseases. A comprehensive biosecurity program requires commitment and has significant financial implications. As shown in Figure 1, a biosecurity program is an investment that provides the foundation to attain critical goals such as flock health, animal welfare, optimum performance, and sustainable production.

Biosecurity is defined as a comprehensive set of policies and practices to prevent the introduction and spread of disease causing organisms. It serves as the first and main barrier of protection against all diseases. A comprehensive biosecurity program requires commitment and has significant financial implications. As shown in Figure 1, a biosecurity program is an investment that provides the foundation to attain critical goals such as flock health, animal welfare, optimum performance, and sustainable production.

Poultry production in the 21st century has evolved into a sophisticated multistep process, and flock health is the number one priority for optimizing production and ensuring welfare, profitability, competitiveness, and sustainability. Biosecurity is a pillar to preserve flock health, and producers around the world realize this is not only the right thing to do but also makes good business sense.

Risk management and biosecurity

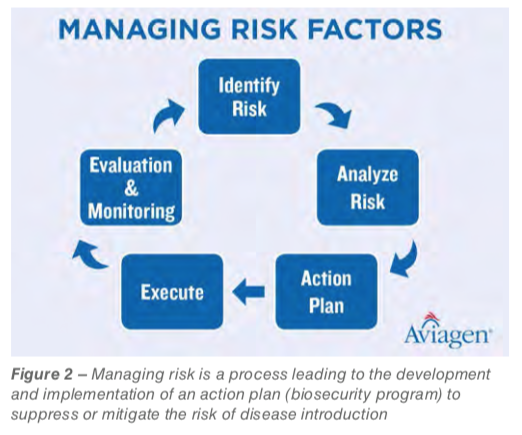

Managing risk starts by identifying factors that can introduce diseases. Recognizing and understanding the risk is a crucial step in designing an appropriate farm-based biosecurity program (see Figure 2). Once a relevant risk factor (potential input) is identified, an action plan comprised of suitable biosecurity practices designed and executed to eliminate or mitigate the risk should be developed. The next step in the cycle is to measure specific parameters or “critical control points” to monitor effectiveness and progress.

Managing risk starts by identifying factors that can introduce diseases. Recognizing and understanding the risk is a crucial step in designing an appropriate farm-based biosecurity program (see Figure 2). Once a relevant risk factor (potential input) is identified, an action plan comprised of suitable biosecurity practices designed and executed to eliminate or mitigate the risk should be developed. The next step in the cycle is to measure specific parameters or “critical control points” to monitor effectiveness and progress.

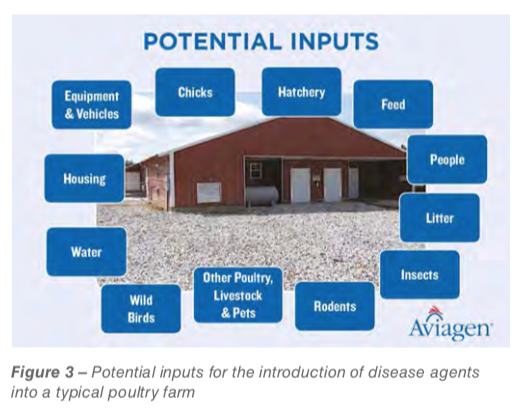

Risk assessments provide an objective look at farms to evaluate strengths and weaknesses. Conducting risk assessments helps to identify gaps and modify protocols, training, and management. Adjustments may be made depending on individual risk levels  posed by outbreaks in neighboring farms or regions. In general, three of the most important factors that must be addressed by the biosecurity program are related to isolation (avoiding or limiting contact with other birds), traffic control (considering all potential inputs that could introduce diseases besides vehicles), and sanitation (cleaning and disinfection of facilities, disinfection of materials and equipment). Figure 3 shows a list of potential inputs that are most commonly covered by policies and operational practices in a farm-based biosecurity program. In 2017 the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), as part of its program standards, established in collaboration with industry partners a list of minimum biosecurity principles and audit guidelines (http://www.poultryimprovement.org – Program Standards, Biosecurity Principles). This list provides a useful template for a typical biosecurity program and an example of cooperation between industry and national and state regulatory agencies. The minimum biosecurity principles are as follows:

posed by outbreaks in neighboring farms or regions. In general, three of the most important factors that must be addressed by the biosecurity program are related to isolation (avoiding or limiting contact with other birds), traffic control (considering all potential inputs that could introduce diseases besides vehicles), and sanitation (cleaning and disinfection of facilities, disinfection of materials and equipment). Figure 3 shows a list of potential inputs that are most commonly covered by policies and operational practices in a farm-based biosecurity program. In 2017 the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), as part of its program standards, established in collaboration with industry partners a list of minimum biosecurity principles and audit guidelines (http://www.poultryimprovement.org – Program Standards, Biosecurity Principles). This list provides a useful template for a typical biosecurity program and an example of cooperation between industry and national and state regulatory agencies. The minimum biosecurity principles are as follows:

- Biosecurity responsibility

- Training

- Line of separation (LOS)

- Perimeter buffer area (PBA)

- Personnel

- Wild birds, rodents and insects

- Equipment and vehicles

- Mortality disposal

- Manure and litter management

- Replacement poultry

- Water supply

- Feed and replacement litter

- Reporting of elevated morbidity and mortality

- Auditing

Building a successful biosecurity plan requires commitment, participation, and a sense of shared responsibility that can only be achieved by developing a robust culture through training, teamwork, communication, and feedback. The success of a biosecurity plan depends on everyone knowing, accepting, and complying with its policies and procedures at all times. Biosecurity must be mandatory and make sense. It must guide daily work activities for all levels of the operation, and be reviewed and improved on a regular basis. Each operation must build their own plan based on well-known principles and adapted to their own circumstances (local challenges), resources, and objectives. Setting unrealistic expectations or unjustifiable logistical obstacles to day-to-day operations will set a biosecurity plan up for failure.

Surveillance and monitoring

Surveillance is a continuous process of observation of a production system to determine the absence or presence of diseases such as low and highly pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI and HPAI). This process can use a combination of active and passive surveillance methods. Passive surveillance is typically conducted when birds are submitted to diagnostic laboratories as a result of increased mortality, and the onset of respiratory signs and egg production drops. In addition, passive surveillance is performed by conducting on-site flock evaluations, identifying signs of disease, reporting to company veterinarians, conducting post-mortem examinations, and submitting samples to a laboratory for diagnosis (activities typically included in a company health plan).

Active surveillance is conducted by performing routine and systematic monitoring procedures to verify the status of commercial poultry flocks in official and/or privately owned diagnostic laboratories. Whether or not commercial operations are mandated to comply with official surveillance programs, it is critically important for companies to design  and implement a science-based monitoring program and to have laboratory resources that can rapidly and accurately detect infections with HPAI, or LPAI viruses with potential to mutate into HPAI (such as serotypes H5 and H7). Moreover, an effective biosecurity program must be verified by laboratory monitoring procedures that can routinely and systematically asses the status of the flocks to ensure their negative status, detect any recent infections, and generate prompt actions to prevent spread to neighboring farms and the production system.

and implement a science-based monitoring program and to have laboratory resources that can rapidly and accurately detect infections with HPAI, or LPAI viruses with potential to mutate into HPAI (such as serotypes H5 and H7). Moreover, an effective biosecurity program must be verified by laboratory monitoring procedures that can routinely and systematically asses the status of the flocks to ensure their negative status, detect any recent infections, and generate prompt actions to prevent spread to neighboring farms and the production system.

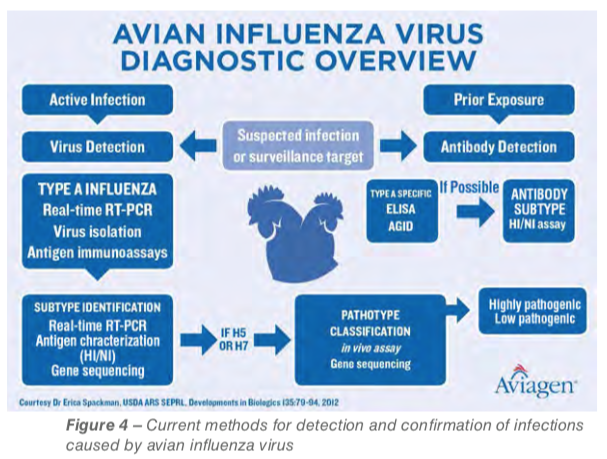

Currently there are several diagnostic methods based on serological (antibody detection) or molecular procedures (antigen detection) that are used to routinely monitor the status of flocks (see Figure 4). These methods are followed by confirmatory tests that include molecular (antigen characterization, sequencing), virus isolation, and evaluations of pathogenicity (pathotyping) in susceptible birds. It is more cost-effective to prevent the introduction of diseases than to develop mitigation strategies after outbreaks have occurred. Maintaining a strong biosecurity culture and performing regular surveillance and monitoring are vital to ensure efficient, animal-welfare compliant, and sustainable poultry production.