Poultry climate is a key factor in faming. High temperatures and a high humidity: in Germany, short periods in the summer months where temperatures as well as humidity are very high occur from time to time. Last year saw an unusually high number of these periods that were often quite long.

According to the global climate database Meteonorm, Germany has had an annual average of 1,000 hours of temperatures above 20 °C in the past. In 2018, this figure rose to 1,800 hours! Additionally, 16 days in 2018 had enthalpy values of more than 67 kJ/kg in the outside air (Big Dutchman measurements by a weather station in Emstek, district of Cloppenburg). This great number of days can be considered an absolute peak. As a result, a question arises: if such heat periods are to happen more often in the future, what can poultry managers do to protect their birds from the consequences?

As humans, we have developed different strategies to make life more bearable during heat waves. We wear light clothes, drink lots of fluids, keep to the shade, reduce the amount of heavy work and use air conditioners. But what about laying hens? Which options do they have to deal with such heat waves, and how does this affect their health and productivity?

Heat dissipation in poultry

To be able to answer these questions, it is important to know that poultry cannot sweat. Due to their plumage, losing heat through the body is also difficult. If poultry is too hot, they will droop their wings and outstretch them away from their bodies. Heat dissipation over the comb, the wattle and the feet is limited as well. Most of the heat is lost through breathing, which evaporates water in the lungs and thus dissipates heat from the body, a process called thermoregulation via evaporative cooling.

As long as the birds are in their thermoneutral zone, i.e. temperatures are between 16 and 24 °C, everything is fine. Since the difference to their body temperature of 41 °C is high enough, they can lose all heat as required.

However, the outside temperature is not the only factor to be considered: relative humidity plays an important role as well. If humidity increases to more than 70 % at an outside temperature of 24 to 26 °C, the water vapour difference between lungs and environment decreases and the birds must increase their respiration rate to be able to dissipate heat. This means that they leave the thermoneutral zone earlier, and heat stress starts at quite moderate temperatures. A very clear indicator for this are panting birds. Panting is therefore an obvious sign that the birds are too hot. An increased respiration rate moreover requires much of the feed energy content and thus costs performance.

Predicting the thermal stress

The German Meteorological Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst DWD, www.dwd.de) offers enthalpy values from May to September and explains: “Enthalpy indicates the total heat content of the air and is used as a reference for thermal stress on poultry.” If the German Meteorological Service predicts enthalpy values of up to 67 kJ/kg and more for the outside air, enthalpy values in the house air will be around 72 kJ due to the heat emitted by the birds. This is already a critical range for poultry.

If excessive temperatures or enthalpy values occur for several consecutive days, layers react by increasing their respiration rate. They will also lower feed intake to relieve stress on their metabolism. This will lead to the following negative consequences:

- Increased water intake due to panting;

- Reduced feed intake to relieve stress on the metabolism;

- Reduced egg weights;

- Lower laying performance;

- Lower egg shell quality;

- Wet manure due to excessive water intake;

- Increased mortality.

What can we do – at the right time and by way of precaution – to maintain layers’ wellbeing and thus their productivity during heat waves?

Structural aspects

Some factors should be considered as early as during the planning phase of a new barn. The barn should have a sufficient height to be able to realise a good air volume. Good insulation is also important. This will not only help in the winter, but also prevent the air in the barn from heating up during the summer, as well as keeping solar radiation from affecting the birds, which would lead to additional thermal stress.

Shading of the barn, especially where the fresh air inlets are placed, should be another focus. Asphalt areas on the farm without any greenery will also heat up the air around the barn. Planting trees and bushes will contribute to cooling the incoming fresh air.

Ventilation concept

The be all and end all for ideal poultry climate control, especially in houses with forced ventilation, is the installation of a modern, sufficiently large ventilation system and the corresponding control technology.

Today’s layer breeds have a very high genetic performance potential. In addition to their need for self-preservation, they also have a high need for performance for this reason. The second need shows itself in greater metabolic activity. This means that current layer breeds produce large amounts of heat, water vapour and carbon dioxide. The air change rates listed in DIN 18910 are usually sufficient to dissipate the birds’ body heat – but not on hot summer days. On such days, an air rate of no less than 4.5 m3 per hour and kg live weight is necessary to cool the birds sufficiently. The air change rate must meet this requirement.

We therefore recommend installing a summer ventilation system using large air inlets in the gable (Figure 1).

Today, this is a common addition to a ventilation system with fresh air entering through wall inlets and exhaust air being extracted through chimneys, which are placed on the roof.

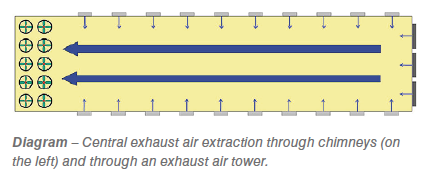

At least two thirds of the air change rate should be designed as longitudinal ventilation in this case, since longitudinal ventilation creates most air movement (Diagram).

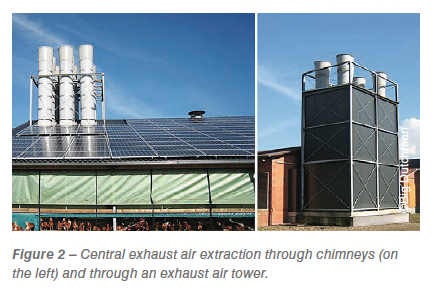

For new barns, it makes sense to install a so-called CombiTunnel ventilation system. If temperatures rise to more than 25 °C on a hot summer day, the climate computer will switch from side ventilation to tunnel ventilation with this system. All fresh air then flows longitudinally through the barn to achieve the maximum air speed and thus causes windchill. This effect can easily be achieved by installing exhaust air chimneys bundled on the roof (Figure 1) or an exhaust air tower (Figure 2).

Measuring and perceiving are not the same thing

Windchill is the difference between the measured air temperature and the perceived temperature as a function of the air speed. If the air temperature is lower than the layer’s body temperature of approx. 41 °C, the birds are able to dissipate their heat to the environment. This heat loss increases with rising air speed. As a result, the bird perceives the air to be much cooler than it actually is. If temperatures continue to rise, however, this windchill no longer works because the temperature difference is too small. Air that is warmer than 40 °C no longer cools down, but instead heats up the bird even more.

Cooling with water

The final technical measure at this point: cooling with water. In hot climate regions, the PadCooling system is very common. The hot fresh air that is drawn into the house through negative pressure ventilation is first pulled through pads that are made of cellulose or plastic and humidified with water. The fresh air becomes more humid and cools down before it enters the barn. Combined with a tunnel ventilation concept, this leads to a very efficient cooling effect that can ensure a good climate in the barn even with extreme heat.

Another option is the so-called spray cooling method. This method is already the standard in broiler rearing houses. For aviary systems, the technology is still in its first steps, due to the concerns that the litter and the aviary itself will become too moist. However, there are no issues with installing such a system in the winter garden. Before the fresh air from the winter garden enters the barn through the wall inlets, it will be cooled down significantly by the spray cooling system.

Free range egg production

Houses for free range egg production must be viewed separately due to their structural differences. A classic negative pressure system cannot be implemented completely since creating a stable negative pressure is not possible with open pop holes. Instead, balanced pressure systems with fresh air chimneys are becoming quite common.

Additional summer ventilation realised by installing large air inlets (shutters) in the gable is recommended here as well. Especially when the pop holes are closed for the night, the house can be aired thoroughly with the cooler night air by opening the shutters. To ensure sufficient air exchange, building the barns and winter garden as high as possible is more important than ever. The house’s roof and the roof of the winter garden should be insulated so that the heat cannot accumulate in the attic. Shade and greenery around the house will also help with this issue. The range should have sufficient shaded areas for the birds as well.

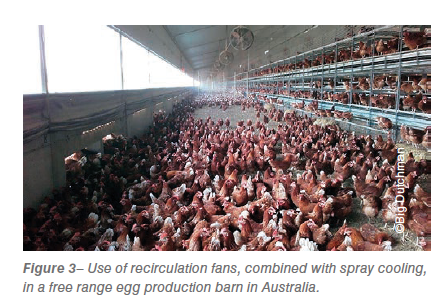

It also makes sense to take a look at regions that often experience high temperatures. In Australia, for example, free range barns with natural ventilation are often equipped with recirculation fans at distances of 10 to 15 m (figure 3). These fans create a windchill simply by blowing air at the birds. From temperatures of 32 °C, a spray cooling system is added.

Management measures

If all factors regarding construction and climate technology have been considered and optimised, there are some management measures the farmer can take to minimise the birds’ heat stress.

- Run the ventilation at maximum level during the night

If temperatures drop during the night or in the early morning, air the house well. The entire barn can be cooled down in this way; the birds are able to dissipate their body heat to the much cooler air and relax.

- Check fresh air and exhaust air every day

Make sure that all air inlets, fans and exhaust air chimneys work correctly every day. Dust deposits, leaves or spider’s webs in front of the air inlets will increase pressure for the fans and thus decrease the air rate.

- Check bird weights daily

During heat waves, it is completely normal that the birds reduce their feed intake from normally 130 grams to only 120 grams. This can lead to lower egg weights and a slightly reduced laying performance. Weight loss, however, can cause problems. This may happen if the laying performance does not return to normal even after the heat wave is over. Keep an eye on the bird weights from the beginning so you can counteract weight loss as early as possible.

Install bird scales in the barn, so one glance at the production computer is enough to know for sure. If you notice a trend of lower weights, you can move the main feeding time to the very early morning hours. Temperatures are still a bit lower at this time of day and the birds will be hungrier. Also check the feed composition and whether adding vitamins to the feed might be an option. Your feed consultant will surely be able to help.

- Check the water consumption every day

The next management measure concerns water intake. With the respective technology, daily water intake is easy to measure. On hot days, water intake is higher, of course. This means that sufficient quantities of fresh and cool water must be available. It is therefore a good and sensible idea to invest in an automatic rinsing system. Bacteria and other germs tend to proliferate in stale water.

Water consumption is usually at approx. 200 ml per bird per day. If this value increases significantly, the effects can be negative. In addition to more playing with the water, the birds may also drink too much, which will lead to nearly liquid excrements. A feed-to-water ratio of 1:1.8 is normal, but it can rise to 1:4 under heat stress.

Splash water and wet manure with a dry matter content of as little as 18 % will cause moist litter, however, and thus increase ammonia emissions and the general humidity in the barn. Use higher ventilation rates to try and get the barn dry again.

- Adjust the lighting program

Feed and water intake as well as the main laying period can be controlled, at least to some extent, using a lighting program that is configured specifically for the summer months. Using a modern control computer, it is possible to switch the birds’ rhythm to the early morning hours.

Review and conclusion

Looking back on last summer, we can say that especially in newer houses, everything went well – this time. In most cases, temperatures were very high, but relative humidity was comparatively low. Farmers using tunnel ventilation reported that “…laying performance was a bit lower and the electricity bill twice as high. But mortality did not increase and our birds weathered the heat quite well.” To be prepared well for the next summer, remember the motto “every degree counts”!

Think in advance about what you as a livestock manager can do so the next summer will be as stress-free as possible for the layers.