Remarkable development of the laying hen inventory and of egg production

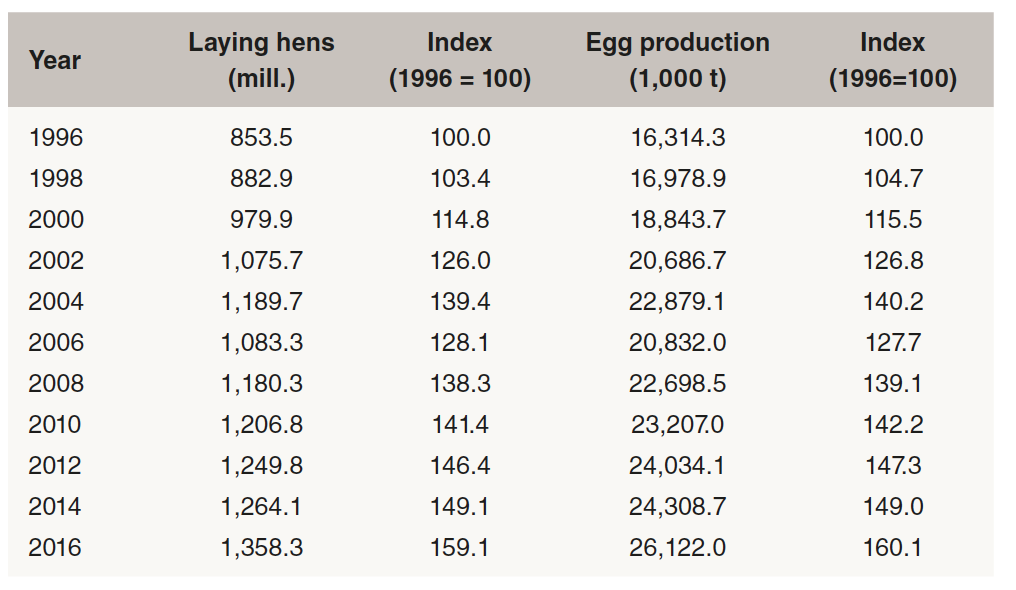

Table 1 shows the development of the Chinese laying hen inventory and of egg production between 1996 and 2016. With the exception of the years 2006 to 2008, a continuous increase can be observed. The decrease between 2006 and 2008 is a result of various outbreaks of Avian Influenza. The disease has been a threat to the egg industry since the late 1990s and besides high economic losses also caused fatal human infections.

A closer look at the data shows that the number of laying hens grew very fast in the first years of the new millennium. This upward trend was then interrupted by disastrous outbreaks of AI. From 2009 on, inventories increased again but the relative growth rates were much lower than in the early 2000s. It was not before 2014 to 2016 that annual growth rates surpassed 5% again. The same is true for egg production. Here, too, the production volume decreased considerably between 2004 and 2006 and it was not before 2010 that a new upward trend began. Since then, the production volume grew by almost 2.9 mill. t. or 12.6%. The production volume for 2016 can be challenged, as the egg demand was calculated at only 24.5 mill. t (see Table 2).

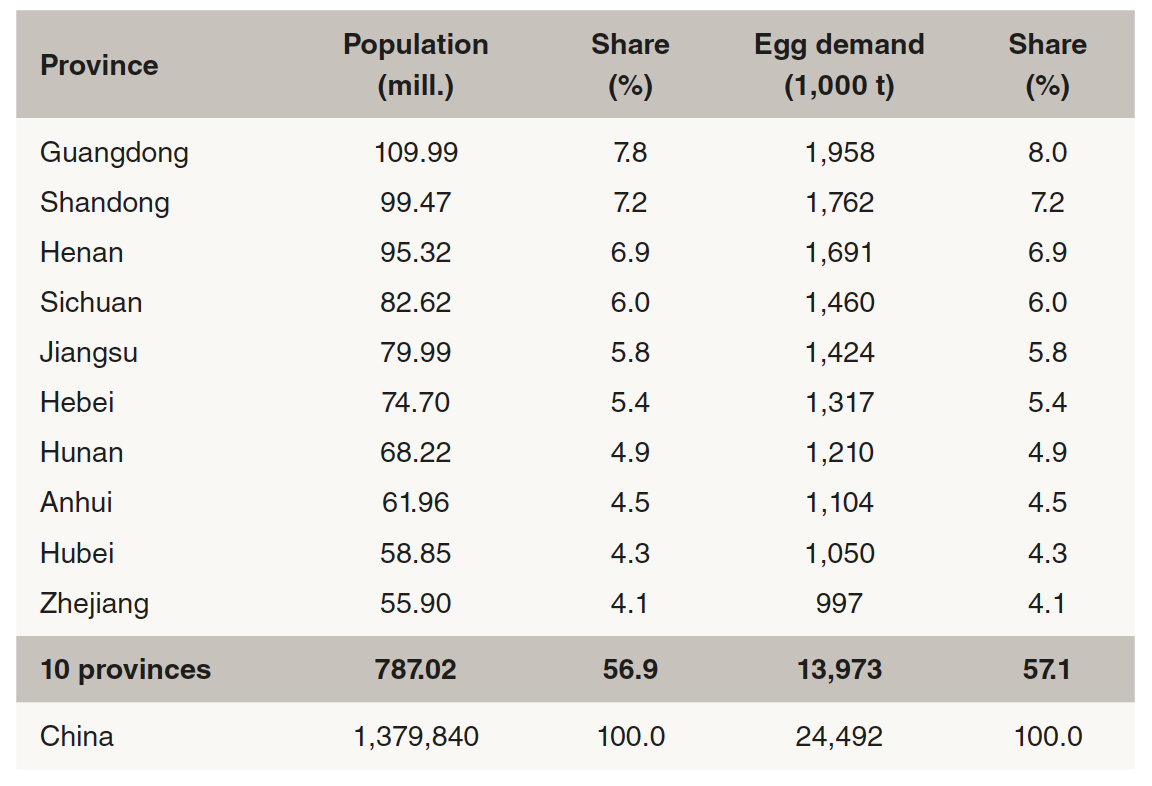

Laying hen husbandry and egg production are not evenly distributed in China. In Figure 1 the spatial distribution of egg production at province level is documented. The egg industry is concentrated in the wide alluvial plains on the east coast between the Yellow River and the Yangtze River. Almost 450 mill. people are concentrated in the five provinces with the highest population, this equals more than one third of China´s total population.

In the ten leading provinces, 56.9% of Chinas population is concentrated; they share 57.1% in the egg demand of the country (Table 2). When comparing egg production and egg demand, a surplus of 2.6 mill. t would result. The production volume for 2016, as documented in Table 1, seems to be overestimated.

The congruency in the spatial pattern of the population and egg production is obvious. In these provinces, large market-oriented companies with modern equipment have been built over the past decade. Despite the dynamical development, the majority of eggs is still produced in comparatively small units. In a detailed study in the leading egg producing provinces, Ning Yang from China´s Agricultural University in Beijing, analysed the farm sizes. About two thirds of the egg farms had less than 5,000 laying hens, and only 0.6 % more than 50,000 hens. In the small farms, feeding and egg collecting was mainly done by hand. The larger farms (> 50,000 hens) only contributed about 8% to the inventory in these provinces in 2013. Since then, larger operations have been built to supply the growing urban population with shell eggs (Photo 1). The new complexes are vertically integrated. These new farms use modern technical equipment, mainly battery cages, automatic watering, egg collection and manure handling. They also prefer hybrid hens against local breeds and are producing feed in own feed mills.

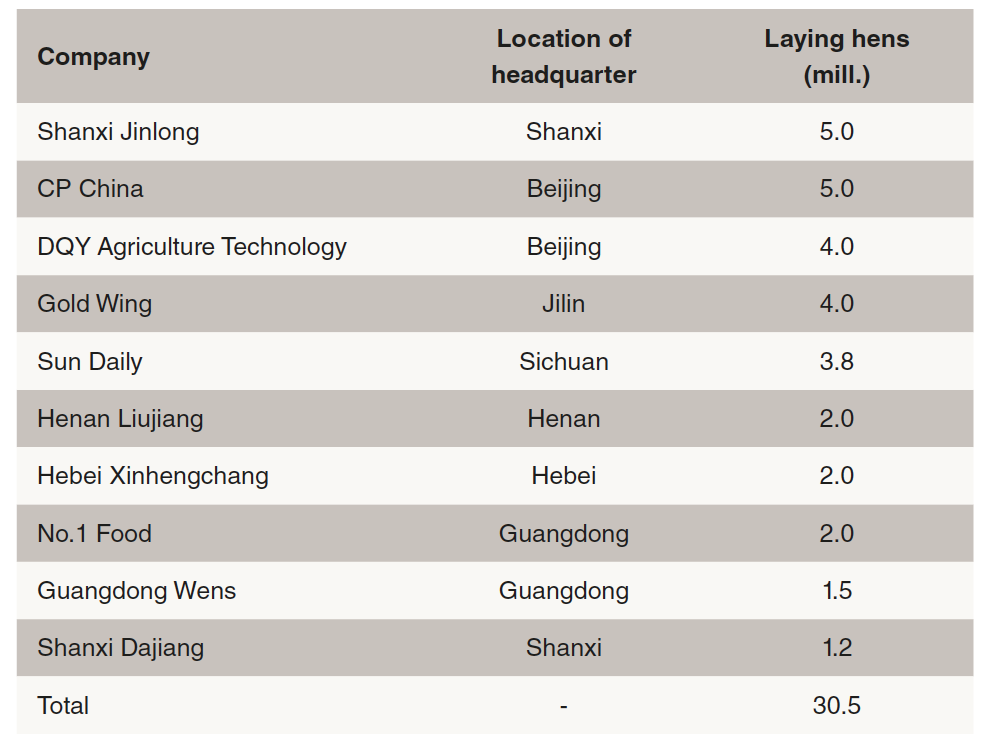

In Table 3, the leading companies and their flock sizes are documented. Compared to the total number of laying hens in China, the share of the ten companies is very small with only 3%. The majority of the laying hens are still kept in medium-sized farms with less than 200,000 birds.

New ways in egg marketing

Egg marketing in China still differs considerably from that in Europe or North America. Only a small amount of eggs is directly sold by the large egg companies to the supermarkets. Labelled eggs are mainly sold on a regional basis. To sell eggs with a nationwide label has not been very successful so far because no company is able to supply the national market.

It can be observed, however, that the big companies are changing their marketing to EU standards and methods. Farms and packing station are separated and eggs are sorted, stamped and branded. Medium-sized producers are mainly selling via a packer or distributor which collects and ships the eggs to the retail stores. Consumers in large cities are buying eggs mainly in supermarkets. Many eggs, especially in rural areas and smaller cities, are still sold at wet markets. They are sold lose, are not labelled and often their quality is not controlled.

A new booming development is the marketing of eggs via the internet or mobile apps. Examples are the company Jingdong and the supermarket chain Taobao, which belongs to the Alibaba-Group. They are not only selling to consumers in the urban agglomerations but also to the growing middle class with an increasing purchasing power in rural areas. The eggs are delivered to the home address. It can be expected that e-marketing will become more important in future. The leading App WeChat, which was used by almost 900 million Chinese in 2017, will play an important role in online commerce. Perhaps egg selling and purchasing may in near future mainly be organized via smartphones, especially in cities, but even in rural areas (Hartman et al. 2017).

The per capita consumption has increased to 282 eggs in 2016, which equals a demand of 24.5 mill. t. To meet the growing demand, the government has implemented a national genetic improvement programme for laying hens (2012-2018) and regulations to reduce and prevent environmental pollution from large-scale livestock and poultry production (NingYang 2013, Shane 2017).

Challenges for China’s egg industry

The main challenges for the Chinese egg industry are outdated production facilities in many small and medium-sized farms, high feed costs, less efficient local breeds, food safety and product quality, high water and energy consumption, environmental problems and insufficient hygiene control in the farms.

The majority of present producing systems are not competitive on the global egg market. This demands a transformation to modern housing systems, vertical integration and inline operation in the egg products industry. Such a transformation will reduce the risk of AI outbreaks and re-establish the trust of the consumers in the quality and safety of shell eggs and egg products. The necessary high investment costs can either be allocated by the government or foreign companies.

References are available on request