In two papers the author will analyse the development of poultry over the past fifty years and document the remarkable growth of global egg and poultry meat production as well as the trade with these commodities.

Hans-Wilhelm Windhorst – The author is Prof. emeritus of the University of Vechta and Visiting Professor at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany

A personal note

“In 1970, I started my academic career at the University of Vechta and immediately began to study the dynamics in intensive animal production at different spatial levels. While my empirical studies initially dealt with Lower Saxony, in particular the counties of Cloppenburg and Vechta, the focus soon widened to EU member states and the USA. The close contacts with leading companies, which produced and marketed equipment for intense animal production, especially for pig and poultry husbandry, and with globally active breeder companies gave me the opportunity to study global patterns and dynamics.”

Hans-Wilhelm Windhorst

A remarkable temporal and spatial dynamics

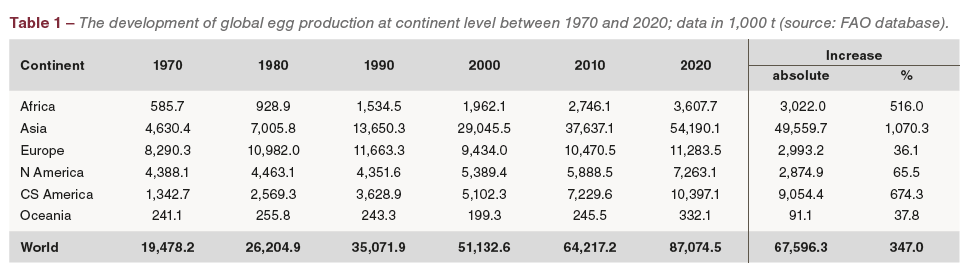

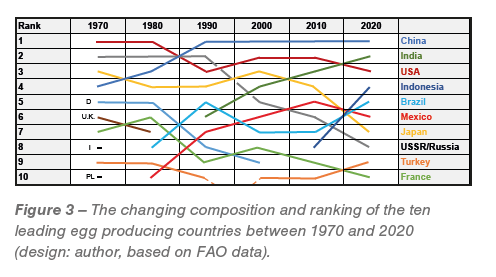

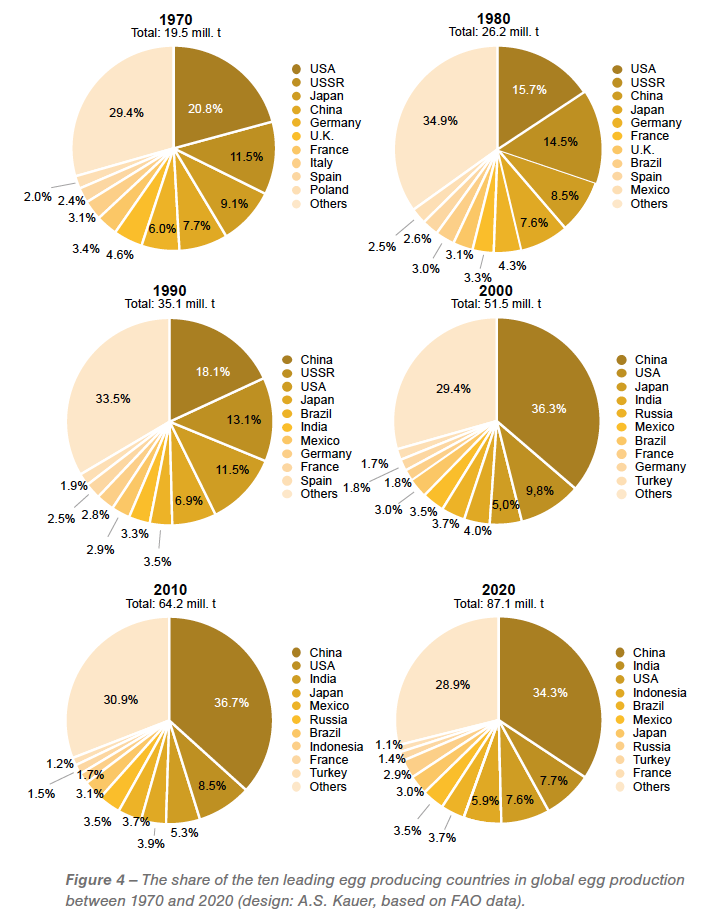

Between 1970 and 2020, global egg production increased from 19.5 mill. t to 87.1 mill. t or by 347%. Table 1 shows that from 1990 on the production volumes grew significantly faster than in the previous two decades. Between 2010 and 2020 alone, it grew by almost 23 mill. t. A closer look at the development at continent level reveals the extraordinary role, which Asia played in the booming development (Table 1, Figure 1).

To the absolute growth of 67.6 mill. t in the decades under review, Asia contributed 73.3%, followed by Central and South America with 13.0%. All other continents fell far behind. The relative growth in Africa with 4.5% was even higher than in Europe and North America. Until 1988, the egg production volume in Europe was higher than in Asia, from then on the extraordinary growth in several Asian countries began, as will be documented in a later part of the article.

To the absolute growth of 67.6 mill. t in the decades under review, Asia contributed 73.3%, followed by Central and South America with 13.0%. All other continents fell far behind. The relative growth in Africa with 4.5% was even higher than in Europe and North America. Until 1988, the egg production volume in Europe was higher than in Asia, from then on the extraordinary growth in several Asian countries began, as will be documented in a later part of the article.

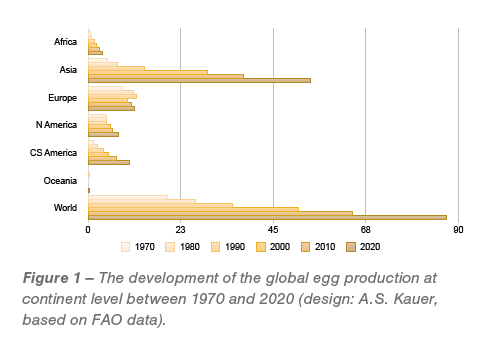

Figure 2 reflects the drastic change in the spatial pattern of global egg production.  In 1970, European and North American countries contributed 65.1% to the global production volume, until 2020, their share fell to 21.8%. In contrast, Asia and Central and South America contributed only 30.7% in 1970, but reached 74.1% in 2020. The far higher relative growth rate in Central and South America in comparison to Europe makes it likely that Europe may lose its second rank during the current decade.

In 1970, European and North American countries contributed 65.1% to the global production volume, until 2020, their share fell to 21.8%. In contrast, Asia and Central and South America contributed only 30.7% in 1970, but reached 74.1% in 2020. The far higher relative growth rate in Central and South America in comparison to Europe makes it likely that Europe may lose its second rank during the current decade.

Considerable changes at country level

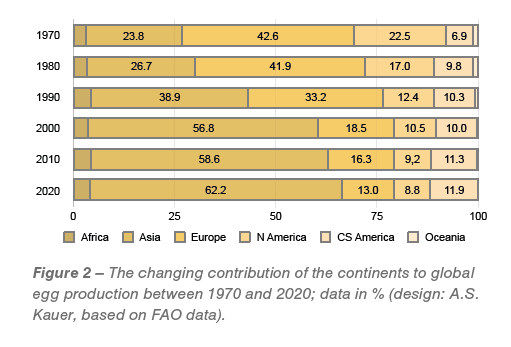

Over the past fifty years, the composition and ranking of the leading egg producing countries changed considerably (Figure 3).  Until 1985, the USA ranked in first place before it was replaced by China, which in the following years remained the unchallenged number one. A closer look at the dynamics reveals some remarkable changes. Between 1990 and 2020, India climbed from sixth to second place and surpassed the USA. Indonesia, which did not belong to the ten leading countries until 2000 climbed to fourth place and increased its egg production by 4.5 mill. t since 2000. While in1970 six European countries (Germany, France, Un. Kingdom, Italy, Spain and Poland) belonged to the top group, in 2020, only France was left, ranking in tenth place. A remarkable dynamical development showed also Brazil, Mexico and since 2010, Turkey. In contrast, Japan fell from third to seventh rank and the former USSR, number two until 1990, showed a deep fall after the political and economic collapse. In 2020, the Russian Federation only ranked as number eight.

Until 1985, the USA ranked in first place before it was replaced by China, which in the following years remained the unchallenged number one. A closer look at the dynamics reveals some remarkable changes. Between 1990 and 2020, India climbed from sixth to second place and surpassed the USA. Indonesia, which did not belong to the ten leading countries until 2000 climbed to fourth place and increased its egg production by 4.5 mill. t since 2000. While in1970 six European countries (Germany, France, Un. Kingdom, Italy, Spain and Poland) belonged to the top group, in 2020, only France was left, ranking in tenth place. A remarkable dynamical development showed also Brazil, Mexico and since 2010, Turkey. In contrast, Japan fell from third to seventh rank and the former USSR, number two until 1990, showed a deep fall after the political and economic collapse. In 2020, the Russian Federation only ranked as number eight.

A detailed look at the dynamics at country level will show the high regional concentration in egg production and the rise or fall of specific countries.

Figure 4 documents the changing shares of the ten leading countries in global egg production between 1970 and 2020.  The lowest value was reached in 1980 with 65.2%, the highest in 2020 with 71.2%. However, the figures do not paint a clear picture of the extremely high regional concentration. In 1970, the four leading countries contributed 49.1% to the global production volume. In 2000, after the dramatic growth of China’s production volume, they shared 55.1%. In 2020, they contributed even 55.5%, a result of the rapid growth of Indonesia’s egg production.

The lowest value was reached in 1980 with 65.2%, the highest in 2020 with 71.2%. However, the figures do not paint a clear picture of the extremely high regional concentration. In 1970, the four leading countries contributed 49.1% to the global production volume. In 2000, after the dramatic growth of China’s production volume, they shared 55.1%. In 2020, they contributed even 55.5%, a result of the rapid growth of Indonesia’s egg production.

A first interim balance can be summarised as follows. Global egg production more than quadrupled between 1970 and 2020, reaching a volume of 87.1 mill. t. Parallel to this remarkable increase, a drastic change in the production centres occurred. Europe and North America lost their leading positions to Asia and Central and South America, which in 2020 contributed almost three quarters to the global production volume. During the dynamical development, the composition and ranking of the leading countries changed considerably. While in 1970, the USA and the USSR were the leading egg producing countries, China and India occupied the first two ranks in 2020. In 1970, six European countries belonged to the top ten group, not counting the USSR. In 2020, only one European country remained with France in tenth place. This comparison graphically describes the drastic changes in the spatial pattern of global egg production.

Egg trade volume comparatively small

In contrast to poultry meat, the volume of traded shell eggs is comparatively small. In the decades under review, only between 1.8% (2000) and 2.8% (1980 and 2010) of the production was exported. The reasons for the low trade volume are the fact that shell eggs cannot be frozen und have a relatively short shelf life. Most of the eggs are produced for domestic consumption. Nevertheless, exports respectively imports are of a considerable economic importance for several countries. The following analysis will document the trade patterns at continent and country level.

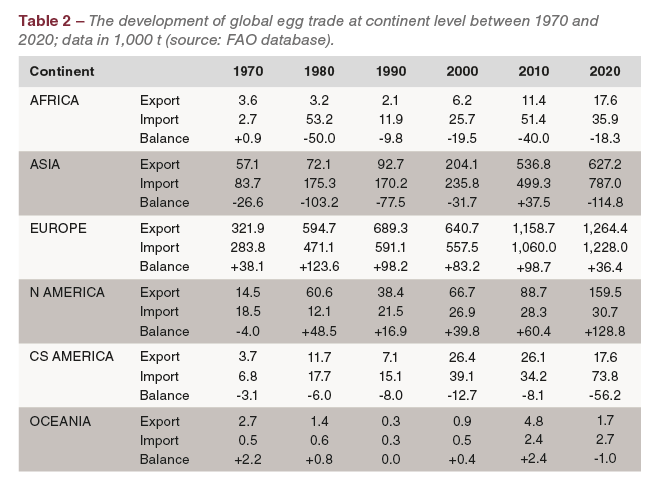

Table 2 provides an overview of the development of egg exports and imports and the trade balance at continent level.

It is obvious that Europe dominated egg trade over the past fifty years. It was not before 2000 that Asia reached higher volumes in egg exports. In all other continents, egg trade was only of minor importance. Europe showed a trade surplus over the whole time-period under review, North America since 1980. Africa and Central and South America had a negative trade balance in all decades, Asia with the exception of 2010.

Considerable fluctuations in egg exports at country level

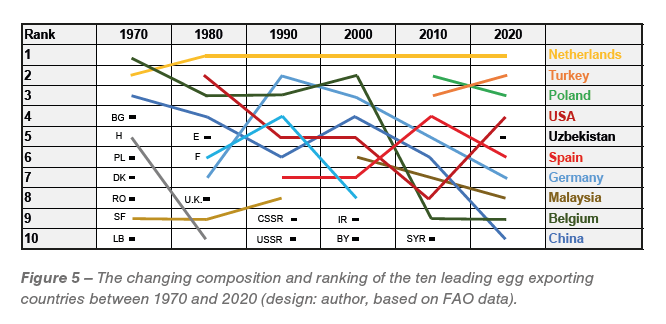

Figure 5 shows the considerable fluctuations in the composition and ranking of the top ten exporting countries. The Netherlands have after several years of competition with Belgium the leading egg exporting country since 1975.

Belgium, number one until 1974 fell to rank nine in 2020, China from rank three to rank ten. Several countries only belonged to the top groups for a short time period, such as Denmark, Romania, Hungary, the United Kingdom, France, the USSR, Iran, Belarus or Syria. Other countries were able to reach a stable position among the leading exporting countries, such as the USA, Germany, Spain and Malaysia. In 1970, Poland played an important role as an egg exporting country as a member of COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance), but could not maintain its position after the collapse of the system. It was not before 2010 that after the remarkable development of the poultry industry as an EU member state, Poland became one of the leading egg exporters again. A similar development occurred in Turkey, which became the second most important egg exporting country in 2011 after years of an extraordinary dynamics in its poultry industry.

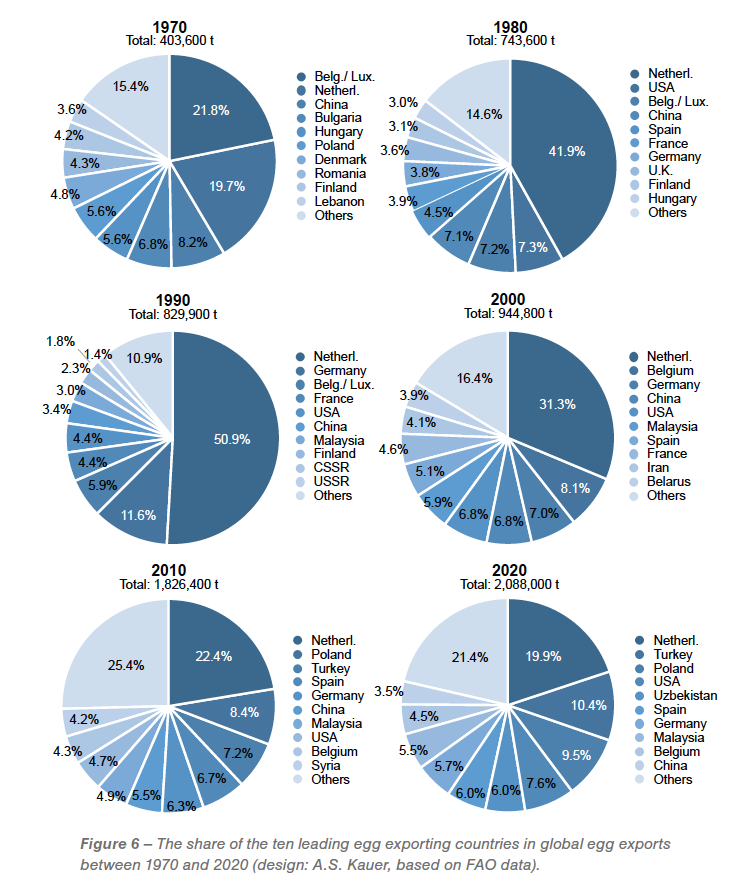

The regional concentration in egg exports was even higher than in production. Figure 6 documents that the concentration increased between 1970 and 1990 and then decreased in the following decades.  In 1990, the ten top ranked countries contributed 89.2% to the global export volume. In 2010, the lowest value was reached with 74.5% before it climbed to 78.5% again in 2020. In 1990, the Netherlands contributed 50.9% to the global egg exports. Until 2020, the country’s share declined to only 19.9% despite an increase in the export volume. The growing production in Turkey, Poland, the USA, Uzbekistan and Malaysia challenges the dominating role of the Netherlands.

In 1990, the ten top ranked countries contributed 89.2% to the global export volume. In 2010, the lowest value was reached with 74.5% before it climbed to 78.5% again in 2020. In 1990, the Netherlands contributed 50.9% to the global egg exports. Until 2020, the country’s share declined to only 19.9% despite an increase in the export volume. The growing production in Turkey, Poland, the USA, Uzbekistan and Malaysia challenges the dominating role of the Netherlands.

Considerable fluctuations also in egg imports at country level

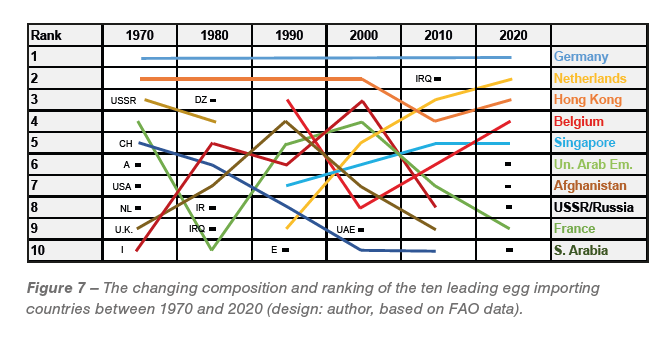

The composition and ranking of the ten leading countries in egg imports fluctuated also considerably (Figure 7) with the exception of Germany.

Worth noting are the changes in the ranking of several EU member states in the decades under review, such as France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Italy. In 1970, France ranked in third place then fell to rank ten in 1980, climbed to rank five respectively four in 1990 and 2000 before it again fell to rank nine in 2020. A similar dynamics showed the United Kingdom. Belgium and Singapore began to import eggs in 1990, in 2020 they ranked as number four respectively five. Of particular interest is the Netherlands. While they resided as number eight in 1970, they became the second largest egg importing country in 2020. This is due to the fact, that Dutch investors bought respectively built large egg farms in eastern Germany after the reunification of the country. They transferred the eggs, which were produced in these farms, to the Netherlands either to export or to further process them. This transfer appears as imports for the Netherlands respectively exports for Germany in the FAO database. Until 1980, the USSR imported eggs from other COMECON countries, but stopped imports after the collapse of the political and economic system. In 2020, the Russian Federation began to import eggs again to supply the population with animal proteins due to the dramatic decrease of pig meat production, which resulted from outbreaks of the African Swine Fever. Because of the war, Iraq’s egg industry was severely hit so that imports became necessary to meet the domestic demand. From 2010 on, the country ranked in second place among the top ten importing countries. When egg production began to recover, imports decreased from 2020 on. In 2020, the United Arab Emirates and S. Arabia imported large amounts of eggs for domestic consumption and for further exports to other countries on the Arabian Peninsula.

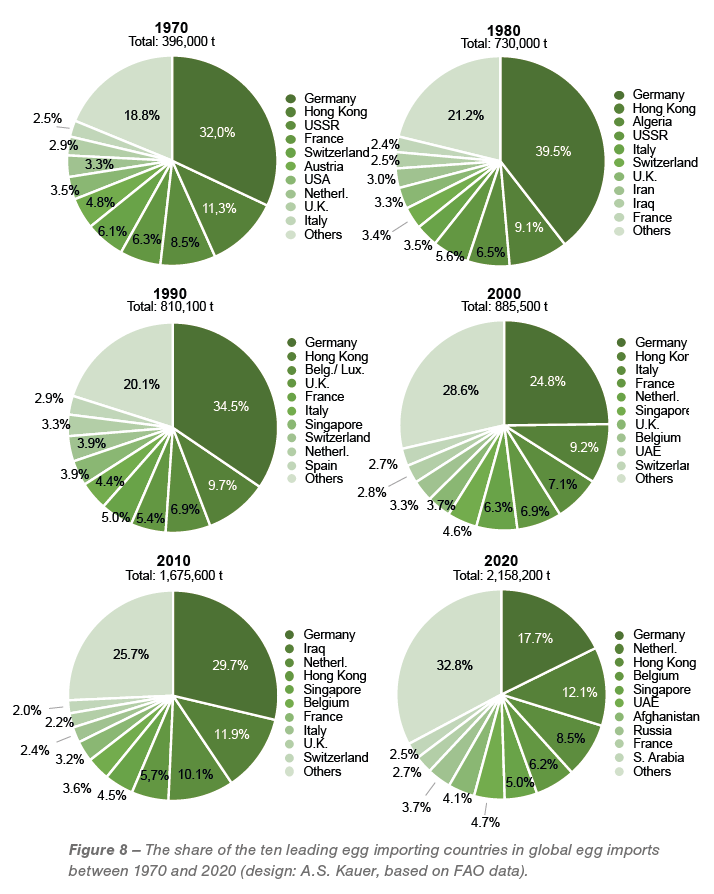

The regional concentration in egg imports reached similar values as in exports, it decreased, however, between 2010 and 2020, a result of the fast growth of imports by Russia and western Asian countries. Between 1970 and 1990, the first three leading countries shared over 50% in the global imports with a peak of 55.1% in 1980. In the following decades, the regional concentration was lower and in 2020, the three top countries only imported 38.3% of the eggs, which were traded globally (Figure 8).  Worth noting is the changing share of Germany in global egg imports. Between 1970 and 1990, the country imported between 32.0% and 39.5% of the eggs, which reached the global market. From then on, the share fluctuated between 28.7% in 2010 and only 17.7% in 2020. From 2010 to 2020, the import volume fell by 100,000 t despite an increase of the per capita consumption. This was possible because of the considerable growth of the inventory by more than10 mill. hens in that decade.

Worth noting is the changing share of Germany in global egg imports. Between 1970 and 1990, the country imported between 32.0% and 39.5% of the eggs, which reached the global market. From then on, the share fluctuated between 28.7% in 2010 and only 17.7% in 2020. From 2010 to 2020, the import volume fell by 100,000 t despite an increase of the per capita consumption. This was possible because of the considerable growth of the inventory by more than10 mill. hens in that decade.

Summary and perspectives

The preceding analysis showed the remarkable increase in global egg production and the drastic spatial shifts. Which were the decisive innovations respectively steering factors behind the success story?

A first innovation was the use of the hybridisation technology in the breeding of laying hens. It started in 1950 in the USA and was in the late 1950s transferred to Europe. Specialised breeder companies began to market hatching eggs and chicks worldwide. A second innovation was the construction of cages with automatic feeding, water supply, egg collection and manure handling. It reduced the necessary labour input drastically and allowed much larger flocks. The very efficient housing system spread parallel with the hybrid hen. A third innovation was the development of vaccines against the Newcastle Disease (1954) and Marek’s Disease (1972). They improved the health status of the laying hens and reduced the mortality rates to less than 5%. A very important steering factor was the development of a compound feed with special additives, which improved the nutrition of the hens. This also contributed to the health of the hens and increased the laying rate considerably. The combination of these factors made it possible to produce large amounts of eggs with a high nutritional value to a reasonable price for the constantly growing global population. Worth noting is, that similar forms of the organization of egg production developed worldwide: vertically integrated companies. As no religious barriers prohibited the consumption of eggs, production and consumption grew worldwide and resulted in a spatial shift of the production centers.

While in 1970 European and North American countries contributed almost two thirds to the global production volume, their share fell to 21.8% in 2020. In contrast, Asia and Central and South America contributed only 30.7% in 1970, but reached 74.1% in 2020, China and India together shared 42.0%. Of the six European countries, which belonged to the top ten group in 1970, only one remained in 2020. This graphically describes the drastic change in the global pattern of egg production.

Although the volume of egg trade only accounted for a share of less than three percent in global egg production, it reached a considerable economic importance for the leading exporting and importing countries. Europe was the dominating continent in egg trade over the time-period which is analysed in this paper and it was not before 1990 respectively 2020 that Asia reached a higher share in exports and imports. Europe was also the only continent with a positive trade balance over the past fifty years. North America showed a trade surplus from 1980 on and Asia only in recent years.

At the turn of the century, new challenges began to confront the egg industry. One is the animal welfare discussion, which in the EU already led to a prohibition of conventional cages from 2012 on and the introduction of new housing systems, such as enriched cages, floor and free-range systems. It will in the coming two decades also reduce the number of hens kept in conventional cages drastically as the development in the USA, Canada and New Zealand show. A second is the threat of the Avian Influenza virus, which has caused disastrous epidemics since 2015 and obviously become endemic in many countries. The success of the vaccines against the Newcastle and Marek’s diseases could show a way out of this existential threat.

Despite these challenges, egg production and the volume of egg trade will further increase because of a growing demand in several threshold and developing countries. The spatial pattern will remain stable. European and North American countries will lose shares in production but Europe will be able to maintain its leading position in egg trade. Although several companies and start-ups have been successful in the production and sale of plant-based egg substitutes, they will not be able to reach shares in the two-digit percentage before 2030.

Data sources and suggestions for further reading

FAO database: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en.

Windhorst, H.-W.: Die Industrialisierung der Agrarwirtschaft (The industrialization of agriculture). Ein Vergleich ablaufender Prozesse in den USA und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Frankfurt a. M. 1989.

Windhorst, H.-W.: Changing patterns of global egg trade: Dynamics at continent and country level in detail. In: Zootecnica international 41 (2019), no. 11, p. 24-29.

Windhorst, H.-W.: The forgotten continent: Patterns and dynamics of the African egg industry: Laying hen inventory and egg production. In: Zootecnica international 42 (2020), no. 9, p. 24-27.

Windhorst, H.-W.: The Champions League of the egg producing countries. In: Zootecnica international 43 (2021), no. 1, p. 26-29.

Windhorst, H.-W.: The forgotten world: the egg industry in the least developed countries. In: Zootecnica international 43 (2021), no. 2, p. 22-25.

Windhorst, H.-W.: The dynamics of the U. S. egg industry between 2010 and 2020. In: Zootecnica international 43 (2021), no. 7/8, p. 22-25.

Windhorst, H.-W.: Patterns and dynamics of the EU poultry industry: a status report. Part 1: Laying hen husbandry, egg production and egg trade. In: Zootecnica international 43 (2021), no. 12, p. 22-26.

Windhorst, H.-W.: Patterns and dynamics of global egg and poultry meat trade. Part 1: Egg trade. In: Zootecnica international 44 (2022), no. 2, p. 22-28.

Windhorst, H.-W.: A documentation and analysis of the AI epidemic in the USA in 2022. In: Zootecnica International 45 (2023), no. 3, p. 8-17.